- by New Deal democrat

Well, this has been just about the lightest week I can ever remember for economic news. Even the JOLTS report, which is usually issued the week after the jobs report, was put off until next week.

So here are a few things to hopefully interest you until something actually, you know, happens.

1. Labor conditions were negative, but there's no cause for imminent concern.

The Labor Market Conditions Index does a good job forecasting the trajectory of the YoY% change in jobs. Here's the long view:

Here is the last 5 years:

We're not any worse than we were in 2012, so there's no cause for panic. On the other hand, the continuing weakness in the LMCI indicates that were are going to get progressively weaker jobs gains in the coming months.

2. Wholesalers' inventory to sales ratio. OUCH!

No updated graph, because FRED waits for retail sales to update total sales and inventory data.

The high frequency weekly data has been pointing to a bottom in the shallow industrial recession. That wholesalers' inventories grew as well as sales falling contradicts that narrative. Bad news. Hopefully a one-month glitch? I dunno.

3. Can you really have a recession when nobody is getting laid off?

Jobless claims:

I mean, seriously, how could that be even possible!?!

4. Speaking of high frequency weekly data...

My rule of thumb for not-seasonally-adjusted data is that, when the series is less than half as good, or bad, as it was at its best/worst YoY, then it has probably made a bottom or top

Here's steel (through February):

Here's steel (through February):

and staffing:

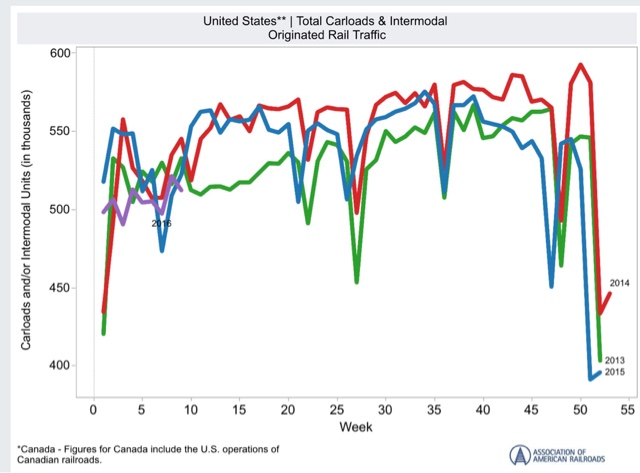

and rail (this year is that purple squiggle on the left):

Steel does look like it has bottomed. Staffing not quite yet, although the YoY comparisons are clearly "less bad" than they were in the September through December frame. Rail is probably benefitting from less bad February weather this year - another two or three weeks of data will tell the tale.