- by New Deal democrat

Real income and spending are two of the most important indicators of the well-being of the consumer. With the general weakening of the economy, I have been looking to see if in particular real spending on goods would sputter. Signs were mixed in February.

Let’s start with the monthly look, followed by the overall look and real personal income and spending since the onset of the pandemic. In February, the PCE price index rose 0.3%. So while nominal income rose 0.8%, in real terms it rounded to up 0.5%. Nominally spending was up 0.4%, but in real terms only up 0.1%. Further, both income and spending were revised downward for January, by -0.2% and -0.1% respectively:

As you can see, in the past year real income has risen significantly, but spending has stalled in the past several months. Since the onset of the pandemic, real income is up 12.0%, while real spending is up 14.7%:

Somewhat concerning ly, real spending is down from December, and only up 0.1% since November. This is important, because as I always say, consumption leads employment.

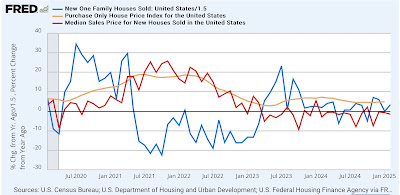

Further, historically it is real consumption of goods (blue in the two graphs below) which declines before recessions. Real consumption of services (gold) not infrequently has continued to increase right through all but the worst downturns. And real consumption of goods in the last several months has turned down:

While real consumption of goods increased 0.7% in February, that only partially reversed the -2.1% decline in January, while real consumption of services declined -0.1% for the month. More importantly, real consumption of goods is down -0.3% since November (right scale), and even services (left scale) are unchanged since December:

But to put that in context, here is the 50 year historical YoY record in real spending on goods up until the Great Recession:

In each case, there was sharp deterioration YoY close to or even below 0 before the onset of recessions.

Now here is the post-pandemic record:

There is no YoY retrenchment whatsoever here, despite the stalling in the past several months.

Next let’s look at the personal savings rate. As expansions continue, consumers tend to get more and more extended, and then retrench just before or at the onset of recessions. Below is the historical record from 1983 into the Great Recession, showing both the savings rate (blue) and the YoY change in the rate (red):

You can see that the savings rate went down, and then increased as consumers retrenched, both during and partly causing the recessions, which is reflected in an increase in the YoY rate.

Here is the post-pandemic record through the present:

In the past several months, there has been a significant increase in the savings rate, but I have been concerned that it reflects unresolved seasonality around the Holiday season. And that seems to be confirmed by the fact that the YoY change continues to be slightly lower, indicating no significant consumer caution as of yet.

Finally, there are two important coincident indicators used by the NBER to help date recessions that get updated with this data.

First, here is real personal income less government transfer payments:

This increased another 0.1% in the month for another new record, up 9.1% since just before the pandemic.

Second, here are real manufacturing and trade sales, a more comprehensive measure of sales than just retail sales, as usual delayed by one month:

These decreased a sharp -1.2% for the month. They are now lower than any month since last August except for October. But because these are for January, they may reflect the unresolved seasonality we saw last month in real income and spending, a point reinforced by a similar drop one year ago in January.

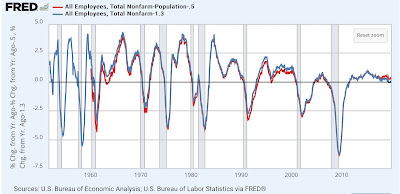

To reinforce that point, here is the historical 50 year record up until the Great Recession:

Real manufacturing and trade sales usually (but not always) decelerate sharply on a YoY basis in the months before a recession.

Here is the YoY post-pandemic record:

There is no sign of a significant YoY deceleration at this point outside of the range of noise.

To sum up: real income and spending continue their expansionary trends. In particular, while several of the data points have stalled out in the last 3 months, this may mainly reflect unresolved Holiday seasonality. There has been no significant deterioration in real spending on goods that shows up in any YoY fashion. Real manufacturing and trade sales display a similar pattern. Despite the “soft” data on consumer confidence, when it comes to savings consumers appear to be confident enough to get a little further out over their skis. In other words, real income, saving, spending, and sales continue to be expansionary.