- by New Deal democrat

Let’s take a deeper look at where employment stands as we begin to see the end of the pandemic in sight.

As I and many others noted last Friday, although with the exception of one month there have been job gains every month starting last May, at the pace of the last few months it would take 2 years or more just to get back to the level of employment just before the pandemic struck.

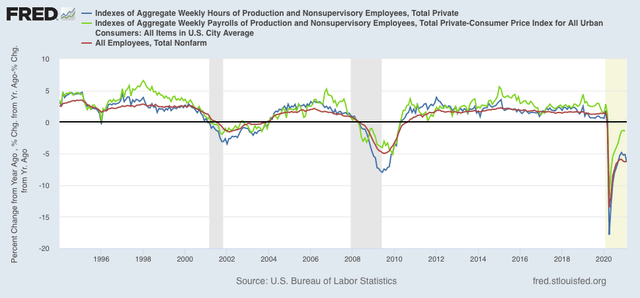

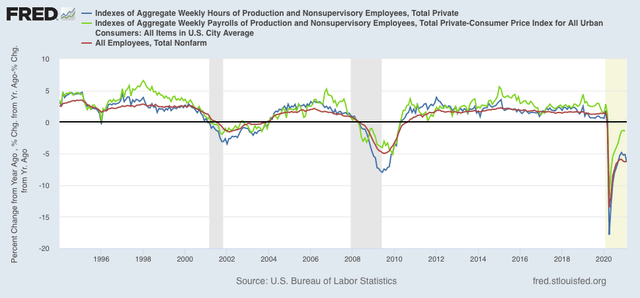

But breaking down those losses between aggregate hours and aggregate payrolls is illuminating. Here’s a look at the YoY% change in jobs, hours, and payrolls for the last 3 recessions and recoveries:

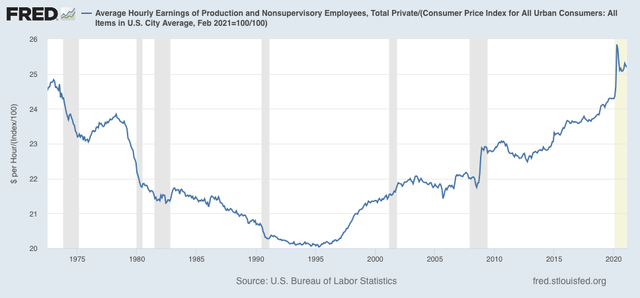

What we can see is that in both 2001 and 2008, hours were cut more than payrolls or jobs. In other words, many more employers reacted to the recessions by cutting employees’ hours rather than laying them off. That hasn’t been the case in the coronavirus pandemic. Both jobs and hours were cut by close to the same amount - I.e., employers laid off employees rather than have them work part time. What was cut far less deeply were payrolls. What this shows is that the brunt of layoffs were borne by lower wage industries. Relatively speaking, higher wage sectors were able to have their employees work from home, and avoided layoffs.

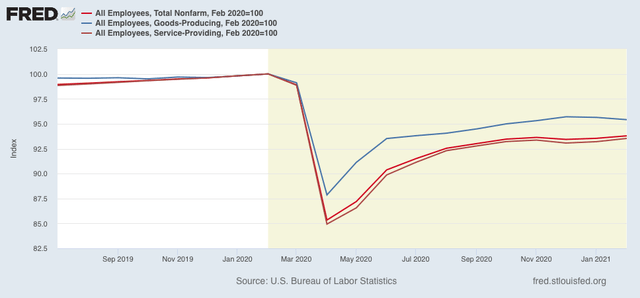

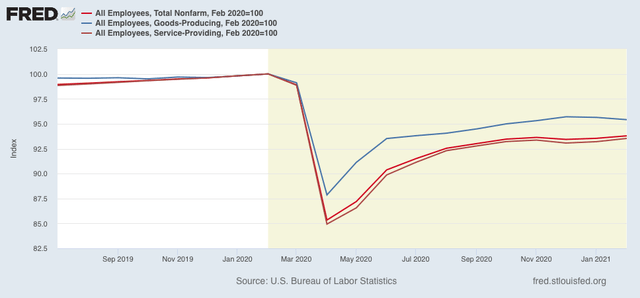

Now let’s slice up the jobs market by sectors to see where the deepest cuts have been. In all of the following graphs, I have normalized employment just prior to the pandemic (as of February 2020) to 100. Thus the graphs show the percentage of jobs lost.

Broadly speaking, employment can be broken down into goods producing and service providing sectors. The latter is by now about 6x the size of the former, which has been deeply cut by offshoring and mechanization. Here’s what that looks like for the pandemic:

Goods producing jobs are down by “only” 4.6% as of last month, while service jobs are down 6.5%.

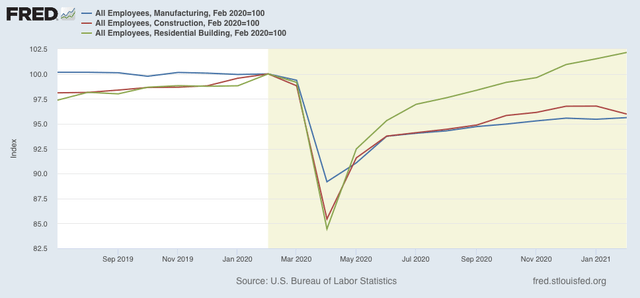

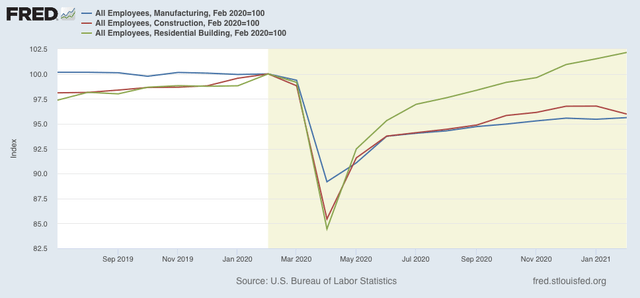

The two biggest portions of goods-producing jobs are manufacturing and construction, shown below along with the very leading sector of residential construction:

The housing boom brought about by super-low mortgage rates has enabled jobs in that sector to grow, while both construction as a whole and manufacturing are both down by roughly 4%, with losses of roughly 300,000 and 450,000 from the pre-pandemic peak, respectively.

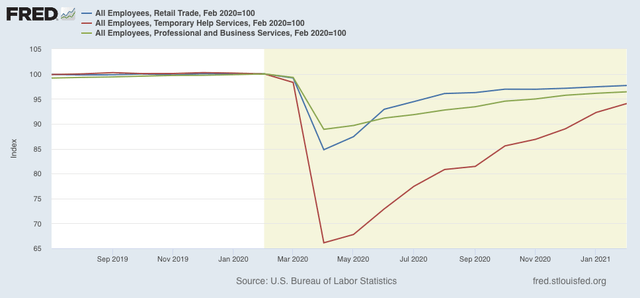

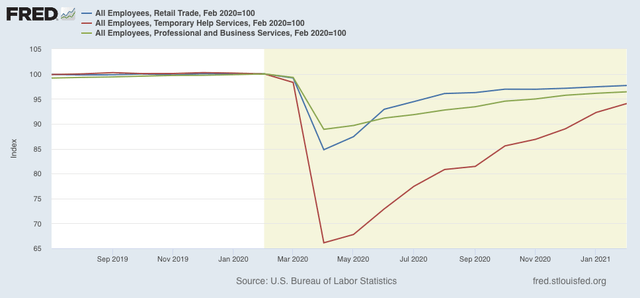

Turning to the services sector, retail trade has not been that badly hit, off 350,000 jobs or -2.3%. Temporary help, another very leading indicator for employment (employers generally hire temps first before extending full time offers), is off -6%, but this is a lower number at 175,000 jobs. The big decline is in professional and business services as a whole, off 770,000 jobs or -3.6%:

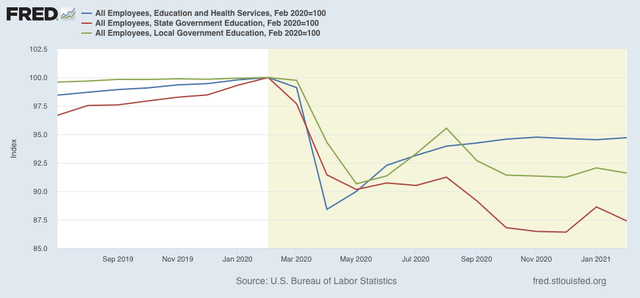

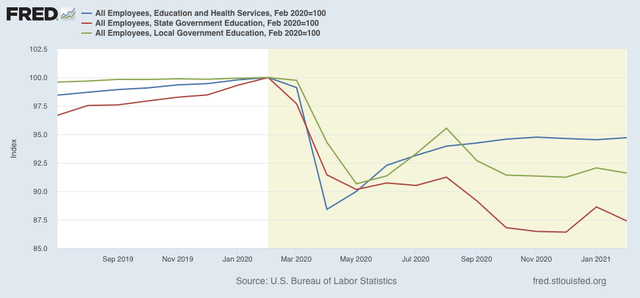

The educational sector has been a much bigger loser, off 1.3 million jobs in total, a decline of -5.3%. Local education is down -8.4%, for a loss of 700,000 jobs, and state education off -12.6%, or 350,000 jobs:

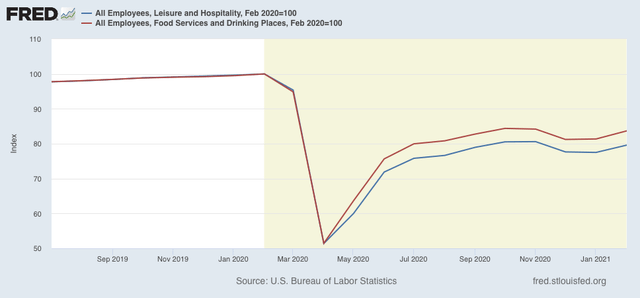

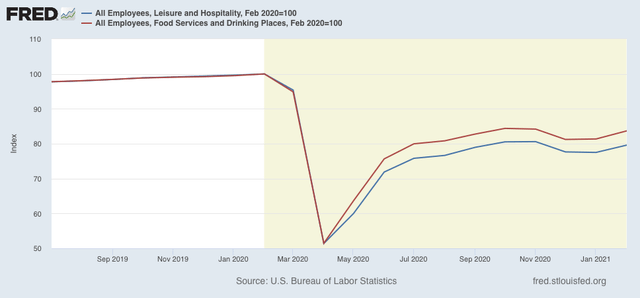

Finally, leisure and hospitality has been the hardest hit part of the economy, with a loss of about 3.5 million jobs, or over 20% of the entire employment in that sector. The food and drinking component is down -16.3%, or just over 2 million:

Putting the data together, we see that the lion’s share of the continuing losses in employment are:

- leisure and hospitality, including food and drinking -3.5 million

- education, -1.3 million

- professional and business services, -770,000

- manufacturing, -450,000

- retail trade, -350,000

- construction, -300,000

Leisure and hospitality, being an indoor activity focused on adults, and the food and drink components requiring being unmasked, is probably going to be the last sector to recover.

Since children are mainly a concern for spreading the disease to adults, once older adults are largely immunized, the worry fades. In other words, it seems very likely that normal, or close to normal, instruction will be a able to begin in September.

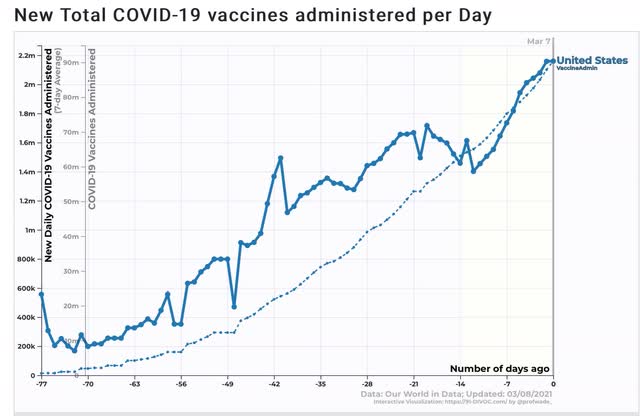

The remaining big areas of losses should all start to improve in tandem with the percentage of the adult population that is immunized, so I would expect to see good improvement throughout the spring and summer. In other words, we might see substantially better jobs reports than we have seen in the past few months going forward from now through summer, and another jump with the beginning of the next school year. It would not be a surprise, though, to see a continuing slump in leisure and hospitality right through the end of the year, or until there is herd immunity (which means a large share of GOP ignoramuses getting vaccinated)