- by New Deal democrat

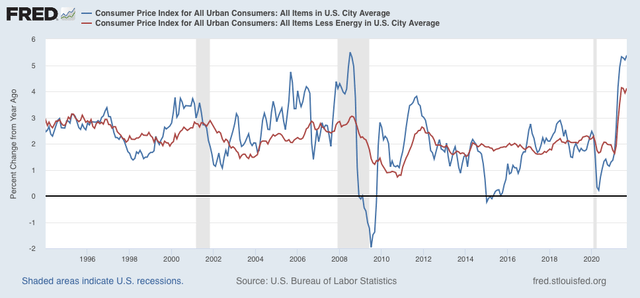

Inflation, along with the expiration of the emergency pandemic payments, is one of the two big threats to this expansion. This morning’s report on consumer inflation for September, at 0.4%, was certainly elevated compared with its typical pre-pandemic reading of 0.2%/month, but on the other hand was the third month in a row of sharp deceleration from springtime, during which inflation averaged 0.8%/month.

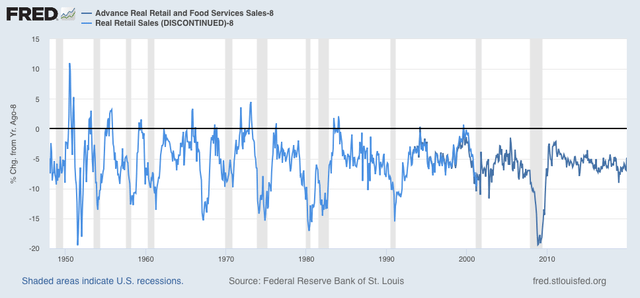

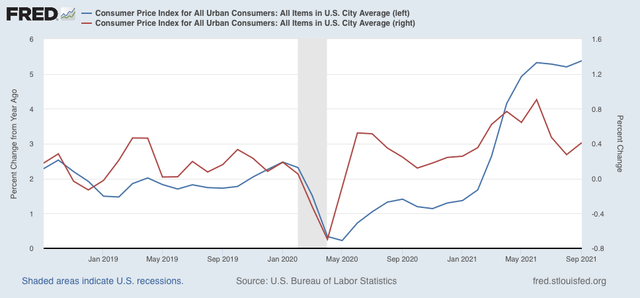

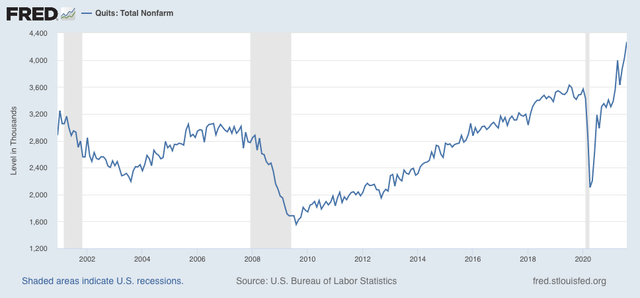

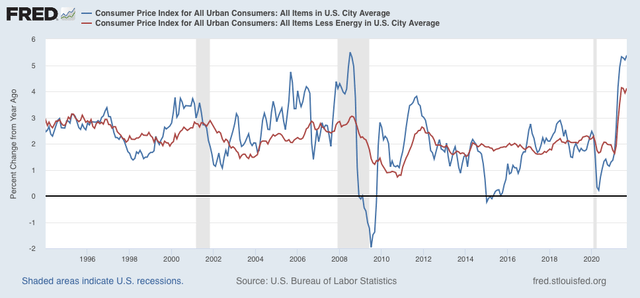

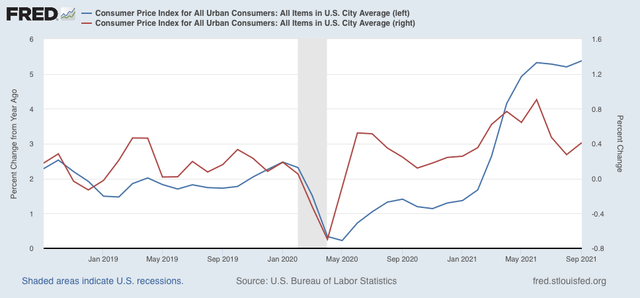

Typically inflation has not been a concern unless inflation ex-gas (red) has been in excess of 3.0%. YoY it is now 4.1%, as it has been for 2 of the 3 prior months. Meanwhile YoY total inflation (blue) is 5.4%, slightly higher than the last 3 months:

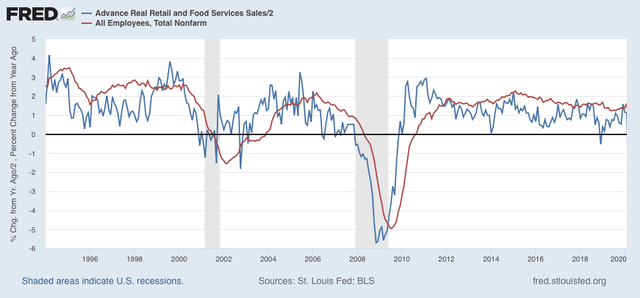

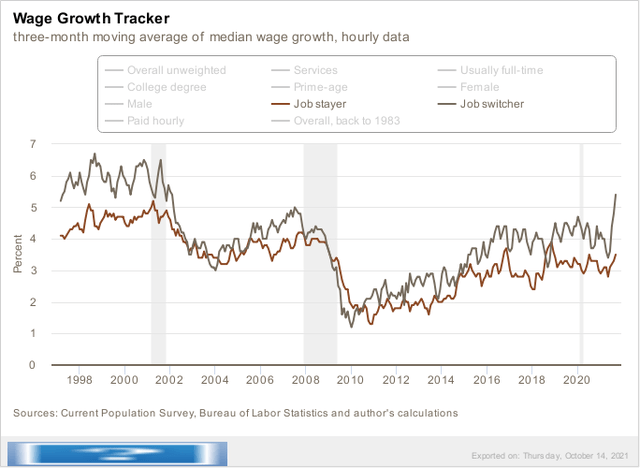

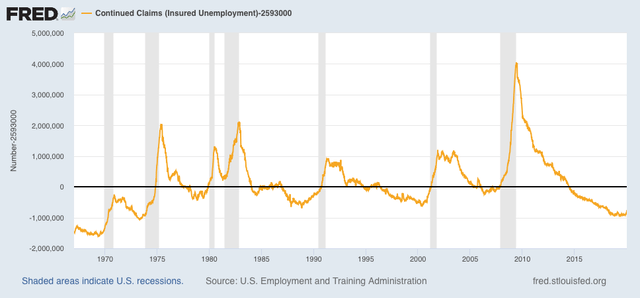

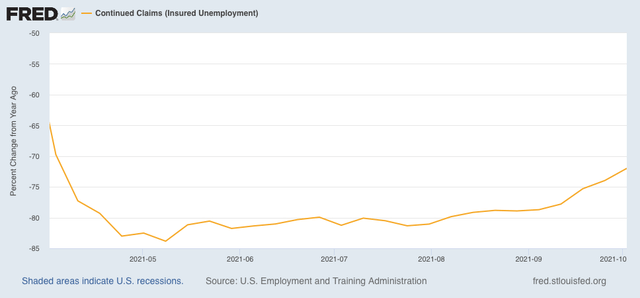

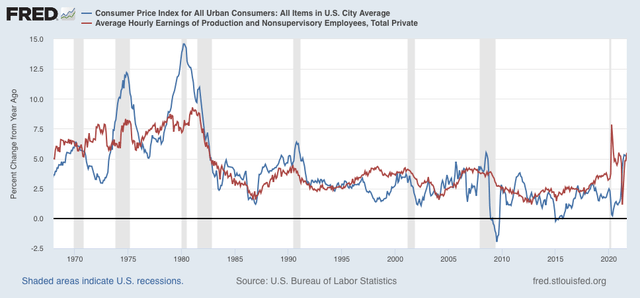

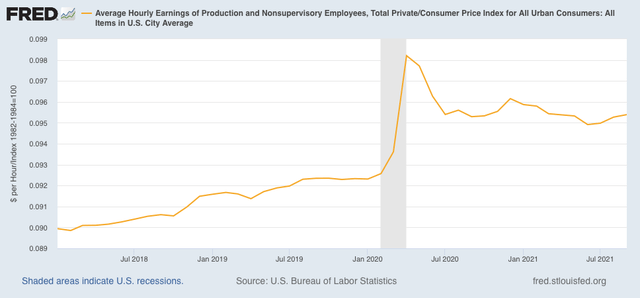

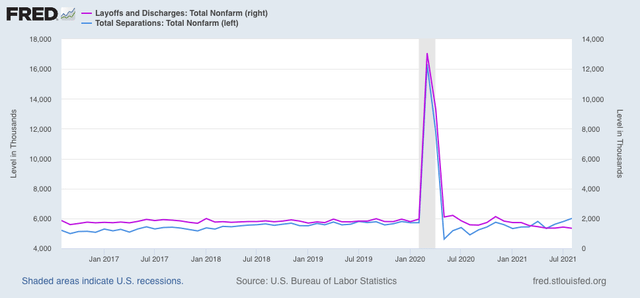

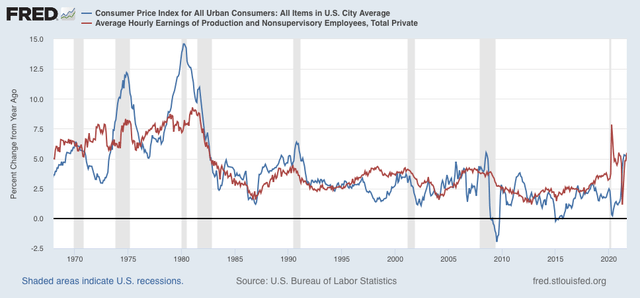

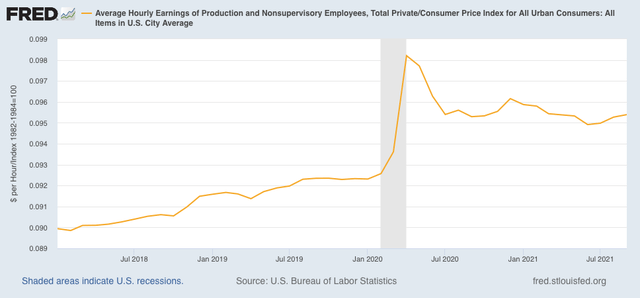

Just as importantly, one of the traditional “real” harbingers of a recession has been wages (more broadly, household income) failing to keep pace with inflation:

Since April, on a YoY basis wages had failed to keep pace with inflation. In September, they eked out a 0.1% gain.

In Absolute terms real wages have been more or less flat for over a year:

This does not necessarily portend a recession, but it is certainly consistent with a sharp slowdown.

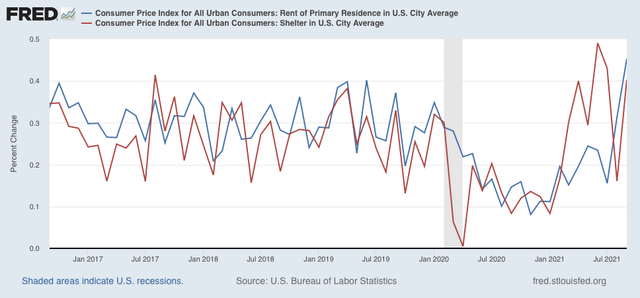

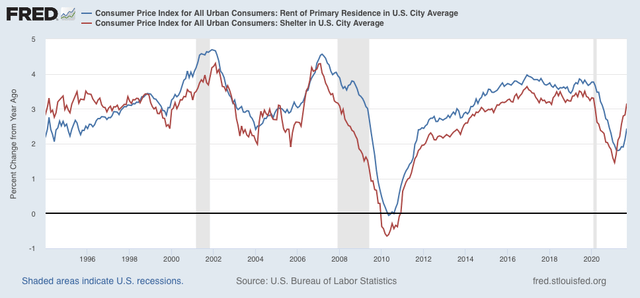

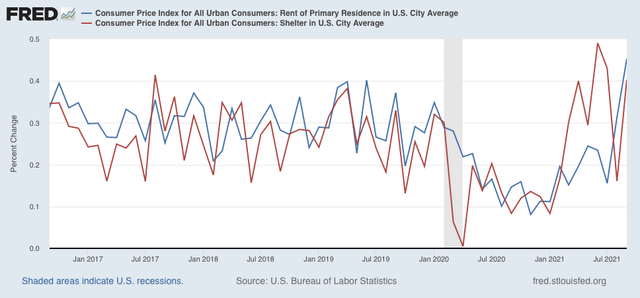

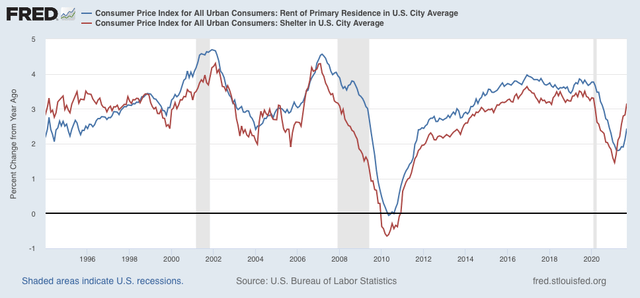

Taking a somewhat more granular look at inflation, housing (shelter) is over 1/3 of the entire index, and reflects households’ biggest monthly expense. The bad news is that on a monthly basis both inflation in shelter (blue in the graph below) and rent increases (red), which had been within their normal ranges in August, are now both running hot (particularly with the expiration of the eviction moratorium):

This has caused the YoY indexes to also turn up:

This will bleed over into the general shelter inflation index, which has already been telegraphed for many months by price increases as measured by the FHFA and Case-Shiller Indexes.

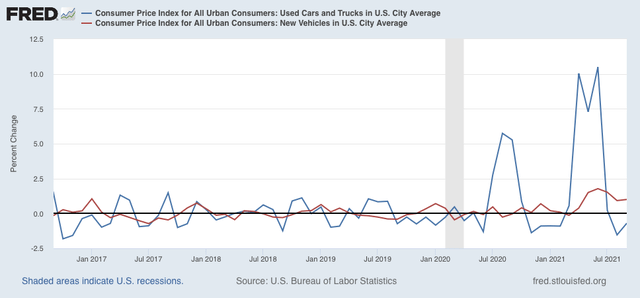

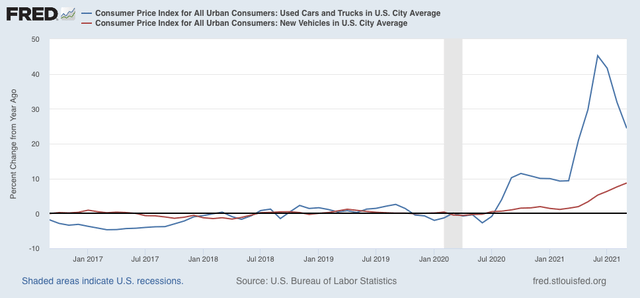

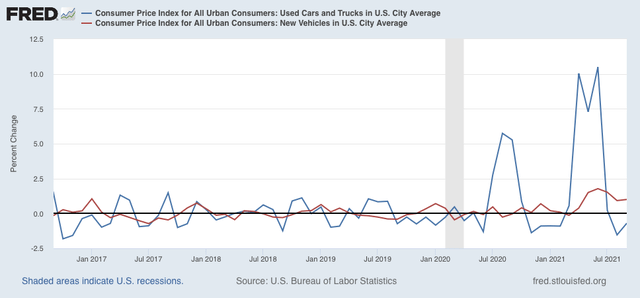

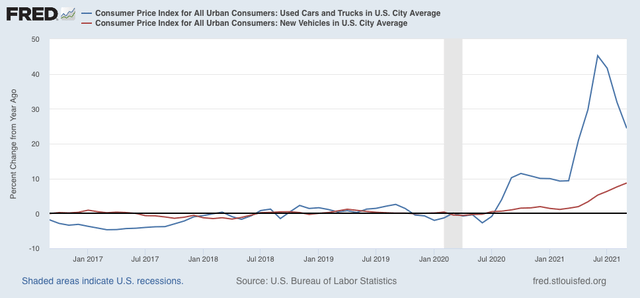

Turning to motor vehicles, new car prices (red) continued to increase at an elevated pace in September, while used car prices (blue) hit a wall in July and have decreased for two month is a row since then:

On a YoY basis, used car prices, which had been up over 40%, are now up “only” 24%, while new car prices are now up nearly 10%:

Finally, although I won’t bother with a graph, there have been renewed gas price pressures in the past several weeks, with prices up about $.10/gallon in that time.

What is the conclusion from all of this?

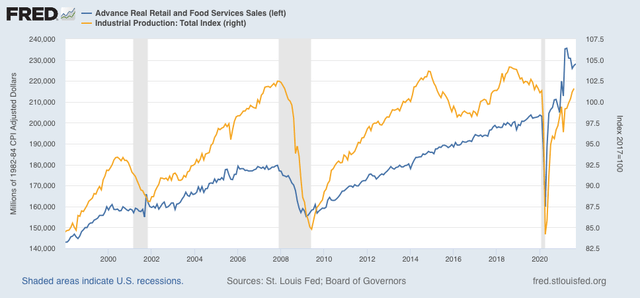

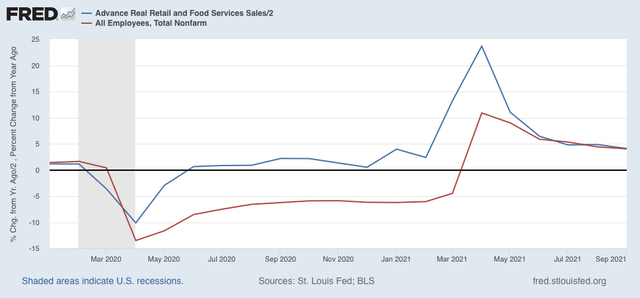

First of all, price pressures in these very important sectors of the consumer economy - housing, vehicles, and gas - are constraints going forward into 2022. As I wrote in connection with last month’s report, heightened inflation has gone on long enough now that I expect some damage to show up in consumer spending. It hasn’t yet, probably because in the aggregate personal savings is up over 20% since just before the pandemic began. That’s quite a cushion! Additionally, “real” wage earnings have generally kept pace with inflation, as opposed to declining, so that suggests that consumers can maintain at least a steady level of “real” spending - and it is spending that drives production and jobs.

Secondly, there has been a real deceleration in inflation between the second quarter, during which consumer prices increased at an 8.4% annualized pace (red, monthly right scale vs. YoY, blue, left scale), and the third quarter, during which they increased at a 6.6% annualized pace:

I expect inflation in both wages and consumer prices to decelerate further from here, with a very important caveat that inflation in rents is a wild card.

To me this adds up to a sharp slowdown in the economy, but not enough evidence at this point - certainly not in the long or short leading indicators - to suggest a recession in the immediate future.