- by New Deal democrat

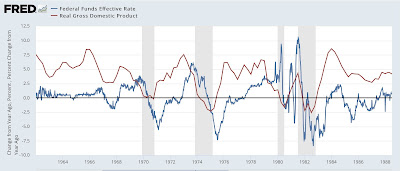

Yesterday the Fed raised rates another 0.75%. In the past 8 months, the Fed has raised rates a total of 3.75%. This is one of the steepest increases in interest rates ever, only exceeded by the pace of the two 1970s oil shocks (1974 and 1979) and Volcker’s inflation jihad of 1981, as shown in the below graph of the YoY% change in the Fed funds rate. Note yesterday’s increase does not yet show on the graph, so I have subtracted 3.75% to show the current rate as 0:

How does that compare historically? In the 1970s, the Fed reacted to inflation rates as high as 12.2% (November 1974) and 14.6% (April and May 1980) by hiking rates from 3.3% to 13.0% in the 2.5 years between February 1972 and July 1974, and from 10.0% to 19.1% in the 2 years and 2 months between April 1979 and June 1981, paces of 4 to 4.5% annually, peaking at 5.9% YoY in 1973 and 10.0% in July 1981:

This year peaked at 9.0% in June. As noted above, in 8 months the Fed has already hiked rates 3.75%, a pace of over 5.5% annually:

With the exception of Volcker’s 1981 jihad, this is equal to the steepest pace of Fed rate hikes in history.

We already know the general economic backdrop for this, but I want to focus on two points.

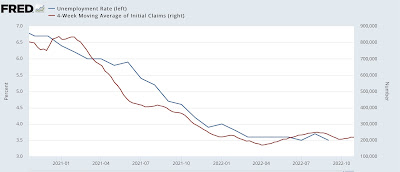

First, the pace of wage hikes, while high by historical standards, has already slowed in the past several months. Via Wolf Street, here is a graph from yesterday’s ADP National Employment Report for October, comparing YoY wage increases for job stayers (7.7%) vs. job changers (15.2%):

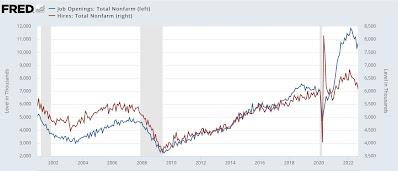

This is the game of reverse musical chairs I’ve been describing for nearly a year. With so many job openings, changing jobs for higher pay has been a lucrative decision.

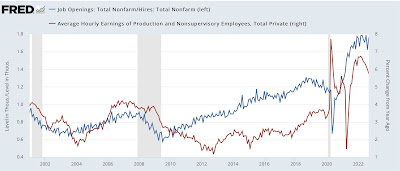

And here is a graph showing the ratio of job openings to actual hires from the JOLTS report (blue) vs. the YoY% change of non-supervisory wages (red):

Generally speaking, wages lag job tightness. Only *after* the ratio of job openings to actual hires has risen or fallen has the pace of wage hikes similarly increased or descreased. The exception has been the past few months, where the pace of wage increases slowed before job openings significantly turned down.

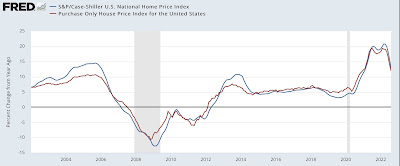

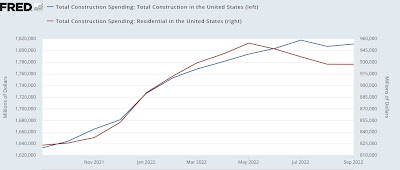

Next, here is the graph I ran a couple of weeks ago as to house prices, showing that, while the YoY% change in house prices is still high by historical standards, both of the big indexes have shown steep deceleration in the past few months (and indeed, on a seasonally adjusted monthly basis have actually turned down):

Finally, here are gas prices for the past year:

In other words, three of the big sources of inflation - house prices, wages, and gas prices - are already moving in the right direction, i.e., decelerating, although in absolute terms they have still incrreased sharply YoY.

For historical comparison, as I wrote several months ago, this is very similar to the immediate post-WW2 Boom of 1946-48, which featured inflation peaking at almost 20% per year (including a similar increase in house prices, and wages). The Fed did *absolutely nothing!* There was a 10 month relatively shallow recession (-1.7% decline in real GDP) in 1948-49:

With that in mind, and since Fed rate hikes operate with a lag, you might expect that the Fed would have signaled a “wait and see” attitude as to whether rate hikes that have already happened would continue to bring inflation down.

But that’s not at all what the Fed, and Chairman Powell, said. Here’s a quote from the official rate hike statement:

The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time. In determining the pace of future increases in the target range….”

And here are a few quotes from Powell’s subsequent press conference:

“We have to raise to the level that is sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation to 2% target over time. We put that into our post-meeting statement. Because that really does become the important question now, how far to go.

“We think there is some ground to cover before we meet that test. That’s why we say that ongoing rate increases will be appropriate. As I mentioned, incoming data between the meetings, both the strong labor market report but particularly the CPI report, suggest to me that we may move to higher levels than we thought at the September meeting. That level is very uncertain, though. I would say we’re going to find it over time.

“As we move more into restrictive territory, the question of speed becomes less important than the second and third questions. That’s why I’ve said it’s appropriate to slow the pace of increases. So that time is coming. And it may come as soon as the next meeting or the one after that. No decision has been made. It is likely we’ll have a discussion about this at the next meeting.”

And…

“Let me say this, it is very premature to be thinking about pausing. When they hear ‘lags,’ they think about a pause. It’s very premature in my view to be thinking about or talking about pausing our rate hikes. We have a ways to go. We need ongoing rate hikes to get to that level of restrictive.”

And …

“I would also say it’s premature to discuss pausing. It’s not something that we’re thinking about. That’s really not a conversation to be had now. We have a ways to go.”

Far from taking a wait and see attitude, Powell bluntly said that the Fed was going to continue to hike, and might continue to hike at similar 0.75% increases in future meetings.

So let’s take a look at what happened in response to the huge Fed interest rate increases in the 1970s and early 1980s:

There were two 18 month long recessions, with declines of -3.1% (1974) and -2.6% (1982) in real GDP.

Since Powell apparently intends to match Volcker, that is my template for the recession that lies ahead.