- by New Deal democrat

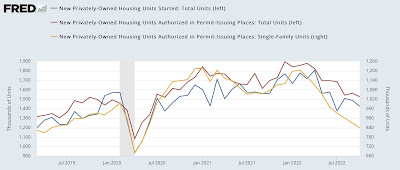

The monthly numbers for housing permits, starts, and single family permits all declined this month. Permits (red in the graph below) declined -38,000 annualized to 1.526 million annualized, and starts (blue) declined -62,000 annualized to 1.425 million, both the lowest since summer 2020. Single family permits (gold, right scale), which have the most signal and least noise, declined -31,000 annualized to 831,000, the lowest since May 2020 and before that, the lowest since April 2019:

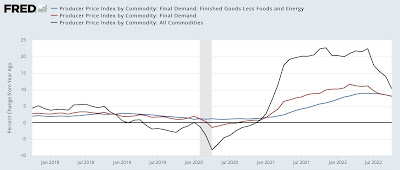

Perhaps more importantly, here’s a variation on a graph I have run many times over the past 10 years, comparing the YoY change in interest rates, in this case mortgage rates (inverted, *10 for scale) with the YoY% change in total housing permits (red) and single family permits (gold):

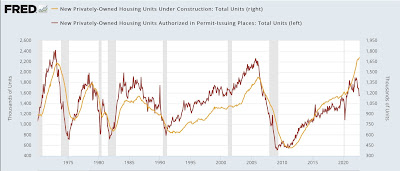

These are well within the ranges of declines that have previously been consistent with recessions, with the exception of 1966, although frequently (not shown) the actual recession hasn’t started until there has been a -40% decline.

As I always point out, interest rates lead housing permits roughly by 3 to 6 months. As shown above, for example, this year mortgage rates turned negative (i.e., higher) YoY in April. Housing permits in total and for single family units followed in August. As of now, YoY interest rates have risen almost 4%, an increase only exceeded by 5% and 6% increases in 1980 and 1982 respectively, which coincided with -50% declines in housing permits (not shown). Thus, we should expect housing permits to have declined by about -40% by about January or February, to levels of 1.100-1.150 million and .700-.740 million units annualized, putting a likely recession start date in the 1st quarter of 2023.

BUT, this time it really is slightly different. In the past, housing permitted and not yet started, and housing units under construction, have typically turned down well in advance of the onset of any recession:

But because of a shortage of building materials, there have been record numbers of housing units that have been permitted, but have not yet been started (blue in the graph below), which appears to have peaked in July, and consequently a big lag in housing under construction (red), which rose slightly again this month, although it has only risen 3.2% in the past 6 months:

Because housing under construction is the actual economic activity, this suggests that residential housing has continued to contribute ever so slightly to GDP growth.

This is reinforced by the generally coincident nature of employment in residential construction (gray in the graph below) compared with housing units under construction:

With the sole exception of the 2020 pandemic lockdown recession, construction, which is an even smoother metric than single family permits, has always peaked at least 6 months before the onset of recession, with a median time of 18 months, and as much as 47 months; and has declined at least 6.5%, and as much as 34%, with a median decline of 20% from peak:

In other words, there is a significant element of “it’s different this time,” in that construction has in the past typically followed a decline in permits by 0 to 11 months, with a median of 5.5 months. Further, a recession has typically followed a decline in construction by between 6 and 47 months, with a median time of 18 months; and has declined at least 6.5%, and as much as 34%, with a median decline of 20% from peak.

We are now 10 months out from the peak in permits, and construction has not yet rolled over. Nor has residential construction employment, which has also typically turned down months in advance of any recession. Thus past history would suggest no recession begins until at least 6 months from now, and possibly much later - depending on how quickly construction rolls over and how abruptly it declines.