- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

The biggest story of the week was the move higher in long term interest rates. This means that the “yield curve inversion” you’ve read so much about in the past year is over. At the same time, long term interest rates (e.g., for mortgages) haven’t moved back high enough to pose a danger to the housing market. In other words, they’re at a “sweet spot.”

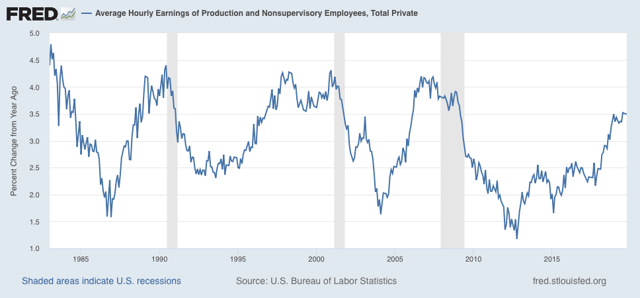

A note on the political implications: my specialty is telling you what the economy is likely to look like a year from now. And one year from now is the 2020 Presidential election. That all of the recent news in the long leading indicators has been improvement means that the economy is very likely to be doing better on Election Day than it is now. Which means that the incumbent candidate’s approval is likely to be higher then than it is now. That doesn’t necessarily mean that Trump wins, but it is fair to say that it does mean that if the Democratic candidate wins, it will be by a lower margin than the present polling suggests. (I owe you this in a much more detailed post, but I wanted to give you the Cliff’s Note version now.)

Anyway, as usual, clicking over and reading my post at Seeking Alpha should be educational for you, and reward me a little bit for my efforts.