- by New Deal democrat

This is a good time to look at the impact - or, better speaking, the lack thereof - of the BA.2 Omicron variant in the US.

Nationwide the 7 day average was 28,961 yesterday:

- by New Deal democrat

This is a good time to look at the impact - or, better speaking, the lack thereof - of the BA.2 Omicron variant in the US.

Nationwide the 7 day average was 28,961 yesterday:

- by New Deal democrat

[Programming note: I’ll discuss some of the innards of the March jobs report in further detail in the next day or two, as well as update the Coronavirus dashboard, with particular emphasis on the likely trajectory of BA.2. Since most States don’t bother any more to report on the weekends, there’s no point in doing that today.]

In addition to the jobs report, Friday gave us updates on manufacturing and construction.

The ISM manufacturing index, and especially its new orders subindex, is an important short leading indicator for the production sector. While the index remained positive, its more leading new orders component stumbled.

In March the index declined from 58.6 to 57.1, and the new orders subindex declined from 61.7 to 53.8, the lowest since 2020. Since the breakeven point between expansion and contraction is 50, these remain positive, (note the graph below does not contain the latest numbers):

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

The big news of the week was the spreading yield curve inversion in the Treasury market.* Needless to say, that puts another bullet in the body of the long leading forecast - but it’s still not negative.

As usual, clicking over and reading will bring you up to the virtual moment on the economic data, and my forecast both the short and long term, and I’ll get rewarded with a penny or two.

*Not to get into too much detail here, but just how negative an indicator a yield curve inversion is depends on (1) how long along the yield curve does it extend? (2) how deep is it? And (3) how long does it last.

Well, it just happened, and it’s pretty shallow for now. But it has definitely spread out along the yield curve. The entire curve from the 3 to 10 year maturity is inverted. The 2 to 10 year spread inverted yesterday. The 2 through 7 year maturities are even inverted vs. the 30 year.

- by New Deal democrat

- by New Deal democrat

Nominally personal income rose 0.5%, and spending rose 0.2% in February. That’s the good news.

The bad news is the personal consumption deflator, i.e., the relevant measure of inflation, rose 0.6%, so real income declined -01%, and real personal spending declined -0.4%.

While both real income and spending are well above their pre-pandemic levels, I have stopped comparing them with that, but instead with their level after last winter’s round of stimulus. Accordingly, the below graph is normed to 100 as of May 2021:

- by New Deal democrat

Initial claims (blue) rose to 14,000 to 202,000, just above last week’s 50 year low. The 4 week average (red) declined 3, 500 to 208,500 (vs. the pandemic low of 199,750 on December 25). Continuing claims (gold, right scale) declined 35,000 to 1,307,000, the lowest number since December 1969:

With Omicron in the rear view mirror, and BA.2 more of a ripple so far, we are having a COVID respite, and basically nobody is getting laid off.

- by New Deal democrat

I have a new post up at Seeking Alpha.

The US Treasury yield curve is fully inverted between the 3 and 10 year maturities.

And you probably have an idea what that means, dearest readers.

As usual, clicking over and reading should be educational for you (if nothing else, by teaching you what the title saying means!) and help inform you of what is likely ahead at some point in 2023.

And reward me with a penny or two for my troubles.

- by New Deal democrat

This morning’s Census Bureau JOLTS report for February shows that the game of musical job chairs continues.

As a refresher, several months ago I introduced the idea of a game similar to musical chairs, where employers added or took away chairs, and employees tried to best allocate themselves among the chairs. Because of the pandemic, there are several million fewer players trying to sit in those chairs, leaving many empty. As a result, wages have continued to increase sharply, as employers attempt to attract potential employees to sit in the empty chairs.

- by New Deal democrat

Very few US States reported over the weekend. The decline in new cases has stalled at roughly 30,000 per day. Deaths are still declining, and currently just below 800 per day.

Since the BA.2 variant continues to generate new headlines, with just about everybody warning of a new wave in the US, let’s take a look at what actually happened in Europe (and remember: there was no new BA.2 wave in South Africa, the Philippines, India, and a number of EU countries where BA.2 took over from BA.1 early).

BA.2 started a new wave in Europe beginning in the last week of February through the first week of March:

A week or two ago, the poster children for Europe’s big outbreak included countries like the UK, Germany, Belgium, Austria, the Netherlands, and Greece. Here’s what they (plus the other major countries of Italy and Spain, plus Portugal), look like now:

Declines everywhere. Italy just peaked earlier during last week, and the UK probably did as well (there was a data dump last Monday which will go out of the average tomorrow).

Here is where BA.2 is still increasing in Europe:

In short, four weeks after Europe’s BA.2 wave started, cases are already declining everywhere except France, Ireland, Luxembourg, Cyprus, and Malta. The last 4 countries have a combined population of 6.5 million. There may be a few small countries I’ve missed, but they wouldn’t materially affect the result.

Last Tuesday, the CDC reported that the BA.2 variant was a majority of new cases in the Northeastern Census region, 40% along the West coast and the upper Midwest, and 30% or below everywhere else. Here’s what cases in the US Census regions look like as of now:

Remember that the appropriate comparison with the CDC report is cases one week ago. Since then, the percentage of BA.2 infections has probably risen by about 15% (but we won’t know until at least tomorrow). One week ago cases were flat to declining everywhere except for the Northeast, where they were up 10%. Cases are still declining in the West, flat in the Midwest, and rising in the South and Northeast now.

For the EU as a whole, cases rose 50% from their bottom since then, and appear to have peaked in the last week. In the US, that would translate to 45,000 cases per day in about 2.5-3 weeks. The worst case countries saw their cases roughly double, which in the US would be 60,000. I’m more inclined to go with the former estimate than the latter.

And since, as of now, there is no new variant on the horizon, I expect a fast decline from peak just as we are seeing in the European countries now.

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

The walls closed in a little more on the long leading forecast this week, as now real money supply is beginning to falter.

As usual, clicking over and reading will bring you thoroughly up to date, and will reward me a little bit for giving you a heads up as to what awaits, economically, in the future.

- by New Deal democrat

This is an update on my yield curve post from earlier this week.

- by New Deal democrat

Initial claims (blue) declined 28,000 to 187,000, yet another new pandemic low (pending revisions!), and the lowest of all time going back nearly 60 years except for weeks during 1968 and 1969. The 4 week average (red) declined 11,500 to 211,750 (vs. the pandemic low of 199,750 on December 25). Continuing claims (gold, right scale) declined 67,000 to 1,350,000, also the the lowest number in over 50 years, since January 1970 (the 1960s were uniformly lower):

Well, I am now pleasantly wrong about having said that “we have probably seen the lows in initial claims for this expansion.” With the Omicron wave all but over (I am increasingly less concerned about BA.2), claims have resumed their downturn, as basically nobody is getting laid off.

- by New Deal democrat

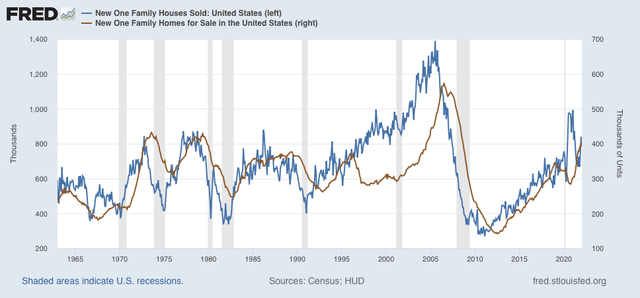

As of this morning Mortgage News Daily shows the 30 year mortgage rate up to 4.72%, 1.9% higher than their lows 15 months ago, and the highest in four years. That means the housing market is in some serious trouble. Let’s take a look at that via this morning’s new home sales report for January.

- by New Deal democrat

- by New Deal democrat