- by New Deal democrat

[Update: I see where Larry Summers has obviously read my piece below, and says, “I agree with NDD!” (Just teasing)]

In the past few days, I have seen a spate of articles and tweets from prominent partisans and economists telling Democrats not to worry about inflation, either because it is a transient supply chain issue, or else because Biden’s infrastructure and “Building Back Better” plans will not add to it.

I dissent. I think the evidence is compelling that inflation *is* becoming a problem. Not because of Biden’s plans - which may not add to inflation - but rather because inflation in the three most important things that consumers either notice or care about - gasoline, cars, and houses - is not so transient at all. In particular, I believe that elevated inflation numbers for housing, which is over 1/3rd of the entire metric, is going to persist for at least another year.

Let me take these in order.

Gasoline

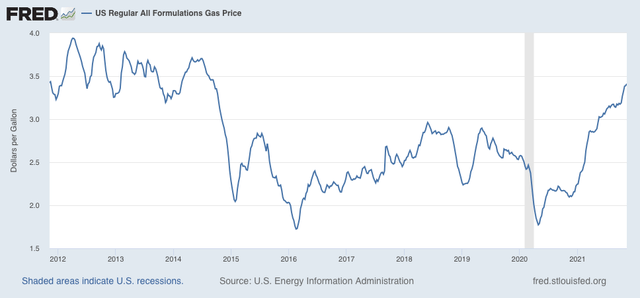

Noticing changes in the price at the pump is the most visible manifestation of inflation. And in the past 18 months, since just after the lockdowns ended, on average the price of gas has increased from $1.77 per gallon to $3.41 one week ago. Not only is this a near-doubling in price, but it is the highest in the past 7 years:

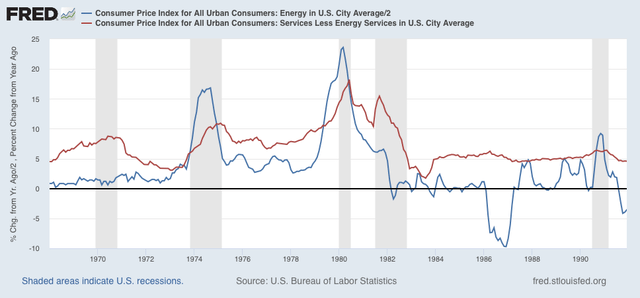

Not only that, but energy prices tend to feed through into the wider economy with a 6 to 12 month lag. This is shown in the next two graphs, which show the YoY% change in energy prices (blue) vs. the YoY% change in all other prices (red). Here are the higher inflation 1970s and 1980s:

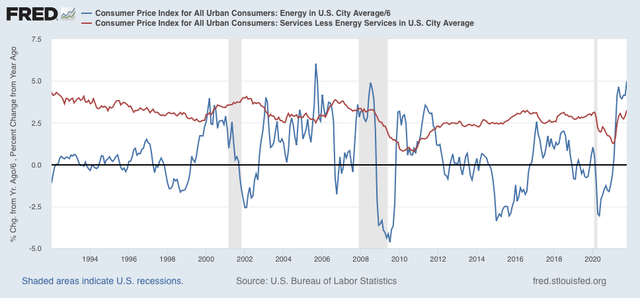

And here is our lower inflation era beginning in 1992:

(Note that I have divided energy prices by 2 and 6, respectively, in the two graphs for scale so that the relationship is better shown).

In 1974, 1979, 1991, 1999, the mid-2000s, and 2011, a substantial increase in gas prices was followed by an increase in the overall inflation rate for everything else. It certainly appears that the same pattern is happening now.

This suggests that, even if gas prices have peaked for now (quite possibly true), that inflation will continue to seep through into the overall inflation rate for the next 6 to 12 months.

Cars

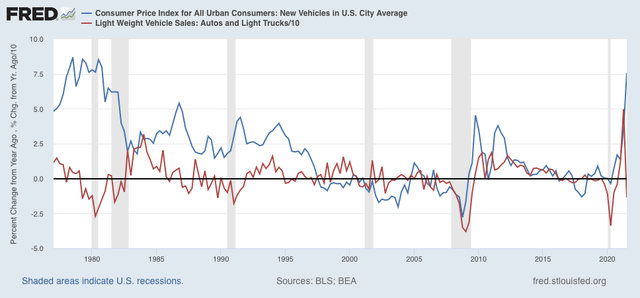

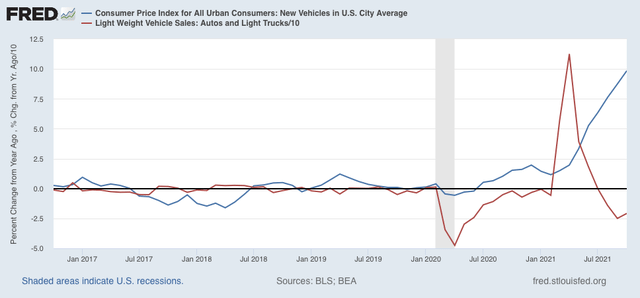

Below is a graph of the YoY% change in prices since 1976 in new motor vehicles (blue) vs. the YoY% change in the number of motor vehicles (excluding commercial trucks) sold (red), averaged quarterly (note sales /10 for scale):

With the sole exception of the period right after the Great Recession, whenever there has been a surge in prices of new vehicles, YoY vehicle sales have turned negative.

Now here is a close-up of the past 5 years, monthly:

The big YoY spike in sales this spring is an artifact of the huge decline during the spring 2020 lockdowns. Since then as prices have spiraled higher, now up almost 10% in one year alone, sales have turned negative.

Houses

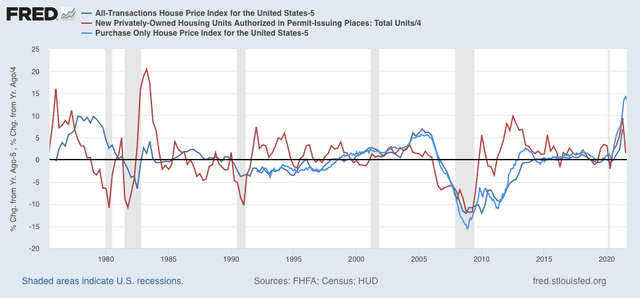

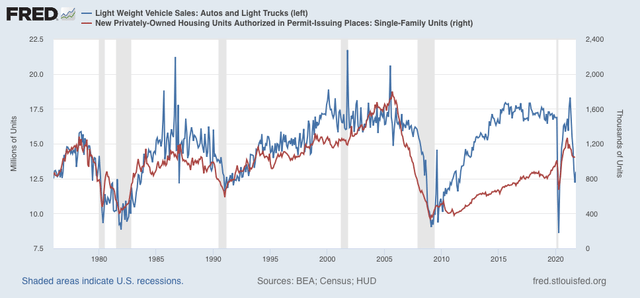

The pattern is similar for housing, as measured by the FHFA (dark blue) and Case Shiller (light blue) house price indexes. Big YoY changes in the price of houses, by 5% or more, have typically been followed by a decline in new houses sold as measured by building permits (red, /4 for scale) (note graph subtracts 5% for both house price indexes, so a 5% YoY increase shows as 0, better to show the relationship):

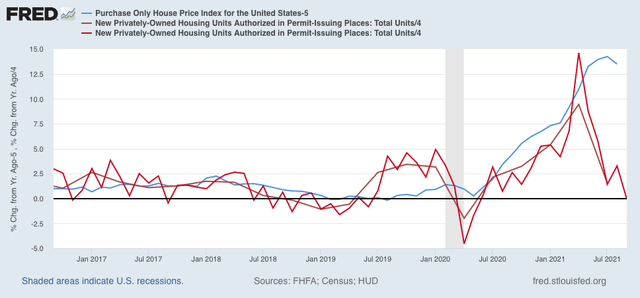

The above graph averages permits by quarter to cut down on noise. Below is the same data for the past 5 years, including monthly changes in permits:

Permits are now virtually unchanged from one year ago.

Consumer reaction

Unsurprisingly, consumers have decided that now is the worst time to buy a house, car, or major household appliances since the 1980-82 recessions:

They’re not wrong, and this isn’t good for Democrats.

Further, not only are the increase in gas prices likely to seep through into wider inflation in 2022, but so is housing, due to the unusual way that housing inflation as measured. I referred to this in an article last week, but want to spell it out further.

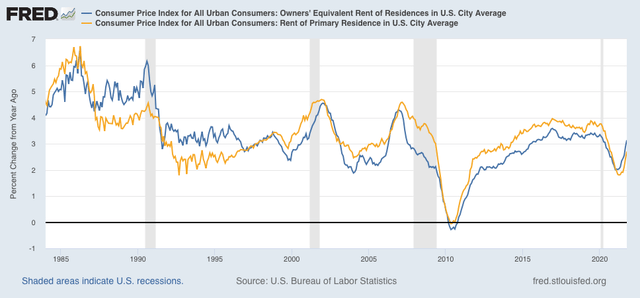

The CPI for housing is measured by something called “owners’ equivalent rent,” or, “how much could I rent my house out for if I wanted to?” It’s bizarre, but for this post just take it as a given.

Owner’s equivalent rent (blue in the graph below) typically tracks very close to the inflation measure for “rent of primary residence,” i.e., how much are renters paying each month? (gold):

Note the big YoY increases in rent, and owners’ equivalent rent, associated with 3 of the last 4 recessions. Note also the big increase in the YoY level of each in the past 6 months.

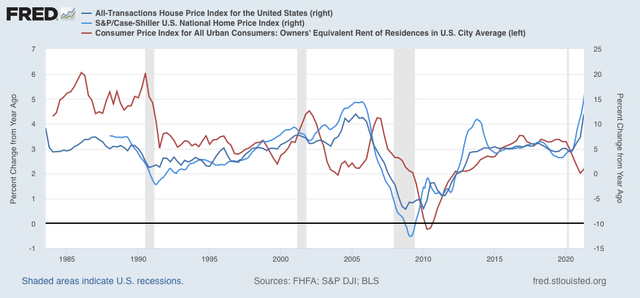

Now here are the two house price indexes (blue and gray, /2 for scale) compared with owners’ equivalent rent (red):

While the relationship is somewhat noisy, it does appear that big increases in house prices have correlated with big increases in owners’ equivalent rent with a lag of 12 to 24 months (bottoms in the former tend to lead bottoms in the latter by about 6 to 12 months). That’s probably because big increases in house prices drive people out of that market, and into the market for apartment rentals.

In other words, not only are higher gas prices likely to feed into higher rates of overall inflation in the next year, but “owners’ equivalent rent” also is likely to contribute elevated readings to CPI during that time frame as well.

Historically, big declines in sales of new houses and cars of over 20% has typically given rise to recessions over the past 40+ years:

New home sales, as measured by permits, is down over 15% but not 20% at present. Car sales, however, are depressed at levels typically associated with recessions before.

Needless to say, continued inflation at rates not seen since the 1970s in 2022 is not “transitory” and is not going to be good for Democrats.

I hasten to add that my array of long and short leading indicators are not pointing to recession at this time. Interest rates and bank lending are very accommodative, and producers are still going full-tilt. The key for consumers is going to be whether they pull back in overall purchases. We will get important information about that in tomorrow’s retail sales report for October.