Saturday, August 25, 2018

Weekly Indicators for August 20 - 24 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

There are about 4 of the long leading indicators that are fluctuating near the levels where their rating of positive/neutral/negative changes. To see the direction they fluctuated in, click on over and put a penny or two in my pocket in the process.

Friday, August 24, 2018

Is the rental vacancy rate a leading signal for the housing market?

- by New Deal democrat

Here is something I noticed while putting together my piece yesterday on the housing market.

Three of the series -- new home sales, existing home sales, and single family starts -- all peaked last November:

That made me go back and think about an anomaly I had noticed, but hadn't figured out, with regard to the rental vacancy rate:

which, according to the graph, peaked in the 3rd Quarter of last year, and has declined since.

It occurred to me that this is probably not a coincidence. If housing unaffordability has become a real constraint for potential buyers, then there should be an increasing number of such buyers who are forced to rent instead -- which would drive down the rental vacancy rate.

It also looks like the rental vacancy rate peaked in 1997-98 and early 2004, in advance of the last two cyclical housing peaks, which I suspect is also not a coincidence.

So, is there a leading signal for the housing market in the rental vacancy rate? My preliminary perusal makes me think it's complicated. I'm chewing it over.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

New and existing home sales for July 2018: UPDATED with link

- by New Deal democrat

Both new and existing home sales for July came in low. New home sales were at a 9 month low, and existing home sales at a 2 year low:

That's enough for both series to be scored as negatives, although the new home sales downturn could easily be revised away, and existing home sales are the least important of all housing indicators.

I'll have a full analysis of all home sales indicators up at Seeking Alpha, and when it comes online, I will link to it.

UPDATE: and here's the link!

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

Pew Charitable Trust confirms the "rental (and ownership) affordability crisis"

- by New Deal democrat

[Note: Unless there is a big surprise, I'll cover existing home sales, scheduled for release later this morning, together with coverage of tomorrow's more important new home sales release.]

In case you thought I was talking through my hat about the general lack of affordability of all types of housing, including both owning and renting, the Pew Charitable Trust has also stepped up with a nearly identical analysis. Go read the whole thing, but here are a few especially noteworthy excerpts:

[A]ccording to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies[, d]emand for rental properties has increased across age and socio-economic groups since 2008....

In the aftermath of the 2007-09 downturn, [... m]any families struggle to save enough for a down payment or lack a sufficiently strong credit profile to meet the stringent underwriting standards that were put in place in the wake of the crisis. But some renters—even with down payment assistance programs— simply cannot afford the monthly payments for homes that in many areas are commanding prices near those of the 2007 market peak

.... The steadily rising demand for rental properties over the past decade has reduced vacancy rates to near historic lows, fueling a rapid increase in rental market prices that has outpaced household incomes for many families. This imbalance is contributing to high rates of “rent burden” .... In 2015, 38 percent of all “renter households” were rent burdened, an increase of about 19 percent from 2001.

It's clear that the very high, and in some cases record cost of new housing has played an important role in the surge of households who rent. Here's my most recent graph comparing median housing costs with median household income (h/t Political Calculations):

That high cost of housing is one driving force behind the surge in rentership:

....[A] 2016 Pew Research Center survey found that 72 percent of renters said they want to buy a home at some point, and most cited financial reasons when asked why they rent. Another recent public opinion poll asked renters ages 18-34 why they were not buying homes, and 57 percent said they could not obtain a mortgage. On the other hand, a recent survey of Americans over 55 found that 71 percent of those who plan to move again said they intended to rent rather than buy. Most renters over 55 cited cost as a driver of their decision and said it makes the most sense for people their age to rent.

In summary, Pew found that

the increased demand for rental properties and their limited supply, along with the lingering effects of foreclosures, demographic changes, and a decline in the rate of renters transitioning to owning, have led to higher rents.

More specifically:

Between 2001 and 2015, the median rent rose from $512 a month to $678, a 32 percent increase.

This is nearly an identical graph to the one I have posted several times, except that it uses the CPI for rents as opposed to the American Community Survey's "median asking rent" metric, in comparison with median household income.

One significant new piece of information that I hadn't considered is the change in demographic profile among renters. They note:

.... In 2015, nearly 43 million American households lived in rental housing, an increase of 9.3 million since 2004 and the largest rise since 1970.... However, unlike the early 1970s when young families drove the increase in renting, the 2015 spike is largely propelled by those 55 and older, largely baby boomers, who are responsible for a 4.3 million jump in the number of renters since 2005.

It seems that Boomers haven't quite finished being "the bulge in the belly of the python" as they compete with the equally large Millennial generation for the scarce resource of apartment housing.

The bottom line here is that incomes simply have not kept up with the costs of all sorts of housing, for both owners and renters. The best way to resolve this problem would be for much more multi-unit housing to be built. Why it isn't being built is something I have not seen authoritatively addressed. Some, like Matt Yglesias, think it's all about zoning. There is also the issue of whether building costs are too high for units aimed at lower income dwellers. Part of the issue may also be an increasing oligopolies of local builders.

Whatever the cause may be, it is a real problem, and interest rate hikes by the Fed, which make mortgages more expensive, are severely counter-productive.

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

How well do weekly purchase mortgage applications forecast monthly housing permits and sales?

- by New Deal democrat

Tomorrow purchase mortgage applications will get their regular weekly update. Their 4 week average went negative YoY last week, for the first time in over three years, after having made a new post-recession high only two months ago.

Of course, I have no idea if this declining trend will continue or not. But if it does persist, how reliable a portent is that for the housing market as a whole?

The purchase mortgage index has had some hits and misses in the past. [Note: Unfortunately the Mortgage Bankers Association does not permit FRED to publish their data, so the below graphs aren't as tidy as I would like them to be.]

First, here's an oldie from the early days of the Calculated Risk blog, showing purchase mortgage applications from 2001 through 2006:

Purchase applications had notable troughs roughly once a year before peaking in about June 2005. Let's compare that with single family and total permits:

Both measures of permits appear to have made equivalent troughs and the overall peak between 1 -3 months later.

But mortgage applications seriously lagged the big decline in housing in 2006-97 by about half a year, and then did not rebound until at least 2013. as shown in this graph of purchase mortgage applications compared with total new plus existing home sales, from the Yardeni blog:

The Mortgage Bankers Association put down their problem during the housing bust to compositional issues, i.e., not adequately picking up newer, non-bank issuers.

Indeed, since 2013, mortgage applications have coincided very well with new+existing home sales, increasing in 2013 with low rates and then decreasing in 2014 in response to the "taper tantrum." Last year - 2017 - both mortgage applications and permits had a downturn during the summer that resolved positively in autumn.

So if the MBA is correct, then if the current downdraft in applications continues, it should be mirrored in the monthly reports on permits and home sales within the next several months. Because "new home sales" are *very* volatile and *heavily* revised, I can't give any kind of specific forecast for this week's report, but in the spirit of making some sort of testable prediction, the argument here suggests that most likely the report will be higher YoY (above 558,000), but below the best levels of earlier this year (672,000).

Monday, August 20, 2018

How "replacement hiring" helps enforce the taboo against raising wages

- by New Deal democrat

Every month when the JOLTS report comes out, I rail against "job openings" as some sort of hard data, and in particular the notion that the US is at "full employment" because the number of "openings" exceeds the number of "unemployed" in the monthly jobs report.

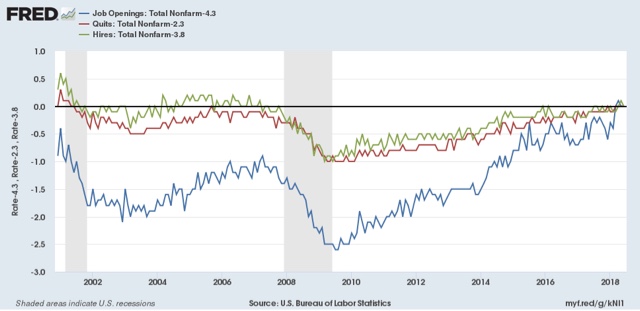

For example, here's a graph I ran last week, which strongly suggests that there has been a taboo against hiring at market-clearing higher wages, leading to an increase in quits to find better-paying jobs:

"Job openings" may be firms holding out for the candidate who will accept the job at the rate they want to pay, and/or keeping the listing open just to troll for resumes.

Well, it turns out it's worse than that.

Sushant Acharya and Shu Lin Wee of the New York Fed issued a report last week in June entitled "Replacement Hiring and the Productivity-Wage Gap." (pdf) in which they

For example, here's a graph I ran last week, which strongly suggests that there has been a taboo against hiring at market-clearing higher wages, leading to an increase in quits to find better-paying jobs:

"Job openings" may be firms holding out for the candidate who will accept the job at the rate they want to pay, and/or keeping the listing open just to troll for resumes.

Well, it turns out it's worse than that.

Sushant Acharya and Shu Lin Wee of the New York Fed issued a report last week in June entitled "Replacement Hiring and the Productivity-Wage Gap." (pdf) in which they

build[ ] a model where firms post long-lived vacancies and engage in on-the-job search for more productive workers. These features improve a firm's bargaining position while raising workers' job insecurity and the wedge between hiring and meeting rates. All three channels lower wages while raising productivity.... The socially efficient outcome features fewer low-productivity jobs and a 10 percent narrower productivity-wage gap.

What is a "replacement hire"? It's a hire that is not for a new position (per the Census Bureau), or in other words, to replace a currently occupied position. It could be in anticipation of worker(s) quitting, or it can also be trolling for "better" workers, in which existing workers will be fired.

Acharya and Wee found that "replacement hiring" increased by over 5% from previous levels in the 2000s expansion, and over 15% in the current one:

In fact, "replacement hiring" has exceeded 1990s levels during the entirety of this expansion, all the way back to 2009 when there was over 10% unemployment!

Further, it is clear that companies are using "replacement hiring" as a means to decrease wage demands from their current workforce. Acharya and Wee calculated the ratio of "voluntary quits" to "hires" from the JOLTS data, and compared that with the above graph on "replacement hiring:"

Only in the past several years has the ratio of quits to hires increased to the level it was at during the very robust 1990s expansion. But, even though it has narrowed, the level of "replacement hiring" exceeds the level of quits. In other words, the gap represents the "job openings" that firms have been using to search for new workers to displace existing workers,

And what is the result? From their Conclusion:

Acharya and Wee found that "replacement hiring" increased by over 5% from previous levels in the 2000s expansion, and over 15% in the current one:

In fact, "replacement hiring" has exceeded 1990s levels during the entirety of this expansion, all the way back to 2009 when there was over 10% unemployment!

Further, it is clear that companies are using "replacement hiring" as a means to decrease wage demands from their current workforce. Acharya and Wee calculated the ratio of "voluntary quits" to "hires" from the JOLTS data, and compared that with the above graph on "replacement hiring:"

Only in the past several years has the ratio of quits to hires increased to the level it was at during the very robust 1990s expansion. But, even though it has narrowed, the level of "replacement hiring" exceeds the level of quits. In other words, the gap represents the "job openings" that firms have been using to search for new workers to displace existing workers,

And what is the result? From their Conclusion:

[A] larger replacement hiring share, the higher market power of firms, larger job insecurity faced by workers, and lower measured matching efficiency in the labor market allow firms to reap productivity gains from replacing workers while still keeping wages low. Compared to the efficient benchmark, private agents in the decentralized economy do not internalize the rat race externality and tend to create too many low productivity jobs. This in turn raises the incidence of replacement hiring and widens the gap between productivity and wages.

In plain english, companies who are constantly holding the threat over current employees' heads that the firm has an ongoing quest to replace them, are companies whose workers don't demand increased wages.

Sunday, August 19, 2018

A graph for Sunday: 2012 Obama voters by 2016 vote

- by New Deal democrat

This is a graph I've been meaning to comment on, that I saw on Vox.com a couple of weeks ago. It breaks down Obama voters from 2012 based on who they voted for in 2016, and adds in Romney voters who voted for Clinton in 2016:

As an aside, note that the graphs measure opinions per group, and definitely *not* their number. Also, it's hardly a complete snapshot of voters, since it doesn't include all the others who voted for Trump. More on that below. But I wanted to make a couple of comments.

First of all, the Obama voters who then voted for Clinton, a third party candidate, or just stayed home all had a pretty similar worldview with the exception of Obamacare. The disaffected voters who abandoned Clinton almost certainly did so because of their views of the candidate, not their views of the issues. For them, Clinton was a warmonger, or a corporate shill, or a crook (because didn't Comey almost directly say so?), or had some other personal shortcoming.

By contrast, the Romney-Clinton voters were closer to the Obama-Trump voters than to the Obama-Clinton voters on everything except for xenophobia (the two issues furthest to the right on the graph). In short, Romney-Clinton voters were garden variety GOPers who simply could not stomach Trump personally -- i.e., the "never Trump-ers." If Trump is the GOP nominee in 2020, at least some of them will refuse to vote for him again.

Here's where it's a shame that the bar graphs don't include Romney-Trump voters. Because it would be nice to compare them with Obama-Trump voters. My sense is that Obama-Trump voters had a strong positive reaction to Trump's populism while either not being offended by, or at least not taking seriously, Trump's xenophobia and racism.

The former Obama-Trump voters are the ideological descendants of the old Dixiecrats: nativist-populists who believe in government programs, so long as those programs benefit *them,* and not ethnic or racial "others." They probably only voted for Obama because the economy was so bad in 2008, and had improved (just barely enough) in 2012.

The latter considered Trump's racist campaign comments as "part of the show." (I read an article about a union official from northeastern Pennsylvania who attended several Trump rallies with his buddies to find out why they were so attracted to him. The "part of the show" line was a direct quote. I wish I had saved the link to the article. Sorry!)

Here's the bottom line I see: if in 2020 the Democrats nominate a reasonably "safe" candidate, the Obama-third party and Obama-nonvoter voters are probably coming back. Depending on the state of the economy, so are some of those who didn't take Trump's racism seriously. (Yes, his racism wasn't a dealbreaker, but imo this group are reachable with reason).

Unless the economy in 2020 is as bad as it was in late 2008, the Dixiecrats are gone, and I see no reason to try to accommodate them.

Saturday, August 18, 2018

Weekly Indicators for August 13 - 17 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

There were 4 long leading indicators that were on the cusp of changing. To see what happened, please put a penny or two in my pocket by heading on over and reading!

Friday, August 17, 2018

Why don't I see any more Doomish commentary on how commercial and industrial loans are turning negative and ensuring a recession?

- by New Deal democrat

Oh, that's probably why.

I told you so, in July 2017, when I published a graph showing that commercial and industrial loans tend to lag the Senior Loan Officer Survey by about 6 quarters, and concluded:

"in the last three quarters, the Senior Loan Officers have reported a slight loosening of standards, which suggests that commercial and industrial loans will continue to flatline through about the end of the year, and improve in 2018."

Which is, of course, exactly what they did.

Which is, of course, exactly what they did.

My extended take on housing permits and starts at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My long-form take on housing sales, updated with yesterday morning's housing permits and starts report, is up at Seeking Alpha.

Like my Weekly Indicators posts, I make a penny or two when you decide to read. So decide to read!

Also worth mentioning: my overall view of housing differs somewhat from that of Bill McBride a/k/a Calculated Risk. Like Bill, I don't think housing has already peaked. But unlike Bill, I see inventory as the tail, rather than the (a?) head. "Months' inventory" typically turns up precisely because sales turn down, so doesn't give me any new information. Also, Bill is really focused on the demographic tailwind, and on "pent-up demand." I'm not sure about the latter, since the bubble years where 2+ million units were added a year, coincided with the demographic *nadir,* i.e., there was a lot of excess housing to be absorbed. As to the former, high enough interest rates and prices will be enough to overcome it. I don't think we're quite there - yet.

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Housing starts turn negative, while permits remain positive

- by New Deal democrat

NOTE: I'll have a more comprehensive report up at Seeking Alpha later, and will link to it once it is posted.

This morning's report on housing permits and starts was a mixed bag.

Permits, while below their single family peak in February and their overall peak in March, were higher than last month. Their shorter term trend is neutral while the 12 month trend remains positive.

Starts, on the other hand, were lower YoY for the second month in a row. Single family starts had their lowest month since last December.

The data isn't up on FRED yet, so here is the Census Bureau's graph:

Because of their volatility, the best way to view starts is as a 3 month average. But even so viewing, starts made a 7 month low. The last two months are equivalent to the low readings of last summer, and no better than average compared with 2016.

Still, because permits tend to slightly lead starts, and single family permits are the least volatile measure of all, the trend in housing must continue to be counted as a weak positive.

This, by the way, contrasts with the weekly data on purchase mortgage applications, which is now down YoY even as measured over a 4 week average; and is among the lowest readings of the last 18 months.

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

Industrial production cools a bit; retail sales continue strong

- by New Deal democrat

Both industrial production and retail sales for July were reported this morning. Let's take a look at both.

First, industrial production increased m/m to another all time high (gray in the graph below), as did manufacturing (red):

At the same time, if you zoom in on the inset, you can see that manufacturing growth has slowed down somewhat this year. It is only up +0.8% in the last 5 months, after having risen 2% in the 6 previous months.

There has been some evidence in both the regional Fed reports and the ISM manufacturing index of a little cooling -- from white hot to red hot -- in manufacturing activity in the past few months. This report is of a piece with that cooling. Tomorrow both the Empire State and Philadelphia Fed regional manufacturing reports will be released, and may (or may not!) give evidence of further cooling this month.

Second, retail sales increased a strong +0.5% in July, but only after a -0.3% downward revision to June. Adjusting for inflation, real retail sales continue to grow on trend:

Real retail sales per capita also continued to grow on trend:

I expect per capita real retail sales to turn about a year before any downturn in the economy as a whole.

Since real retail sales are also a good short leading indicator for employment (red in the graph below), here is growth in both measured YoY:

This suggests continued strong employment growth in the next few months. One thing to watch for is what happens when last September's outsized +1.3% monthly increase drops out of the YoY calculations two months from now.

But the nowcast as indicated by the two reports is continued good growth in both production and consumption.

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

Can the Fed successfully steer between Scylla and Charybdis? An update

- by New Deal democrat

As I type this, the spread between 2 year and 10 year Treasuries is back to 0.25%, the level below which I switch my rating on the yield curve from positive to neutral. Already the spread is tight enough that, even if it never inverts, it suggests a slowdown in the next 6-12 months, as happened in 1984 and 1995 in the graph below of real YoY GDP growth and the Fed funds rate:

One aspect of what is happening in the bond market is that the 2 to 10 year spread is reaching equivalent levels at higher and higher absolute yields. Here's a graph I generated last week, where I normed both the 2 and 10 year Treasury yields to zero at a point where the spread between them was 0.30%:

Note that the two lines intersect (meaning the spread between them is 0.30% three times in the past 45 days: first when the 10 year bond was yielding about 2.83%, then when it was yielding 2.87%, and last week when it was yielding 2.98%.

In other words, the dynamic is that the yield on the 10 year bond has to be at higher and higher levels in order not to be too tight. And the higher those 10 year bond yields, the higher mortgage rates go as well, gradually strangling the housing market.

Can the Fed successfully steer between the Scylla of an inverted yield curve and the charybdis of a housing market downturn?

Possibly. The San Francisco Fed's staff just published a paper in which they suggested that the "neutral Fed funds rate" was 2.5%, as shown in this graph which they generated:

If the Fed stops after two more hikes, it's at least possible that there could be a tight but not inverted yield curve with 10 year bonds yielding roughly 3%.

But the Fed's own "dot plot" from their meetings suggest that they intend to hike the Fed funds rate to at least 3%. If that happens, I see no way the economy doesn't wind up on the rocks.

Monday, August 13, 2018

Gimme Shelter: the rental affordability crisis has worsened

- by New Deal democrat

About half of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, up from 18 percent a decade ago, according to newly released research by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Twenty-seven percent of renters are paying more than half of their income on rent.This is a serious real-world issue. I have been tracking rental vacancies, construction, and rents ever since. The Q2 2018 report on vacancies and rents was released a few weeks ago, so let's take an updated look. In this post I will look at four measures:

- real median asking rent, as calculated quarterly using the Census Bureau's American Community Survey

- two rental measures from the monthly CPI reports

- HUD's quarterly rental affordability index

- Rent Cafe's monthly rental index

As we will see, regardless of which measure used, rent increases continue to outpace worker's wage growth, meaning the situation is getting worse. Most likely this is a result of increased unaffordability in the housing market, driving potential home buyers to become or remain renters instead.

Real median asking rent

In the second quarter of last year, median asking rents zoomed up over 5% from $864 to $910. In the two quarters since, they have remained at that level:

Here is an updated look at real, inflation adjusted median asking rents. The entires prior to 2009 show the interim high and low values from the previous 20 years. Since 2009, real rents have almost continuously soared -- and reached yet another record high in the quarter just ended:

The big increase in unaffordability is unfortunately of a piece with the rental vacancy rate which, after appearing to have bottomed in 2016, tightened again in this report:

| Year | Median Asking Rent | Usual weekly earnings | Rent as % of earnings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 330 | 382 | 86 | |

| 1992 | 401 | 437 | 92 | |

| 1993 | 422 | 450 | 88 | |

| 2000 | 478 | 568 | 84 | |

| 2002 | 545 | 607 | 90 | |

| 2004 | 599 | 629 | 95 | |

| 2009 | 680 | 739 | 92 | |

| 2012 | 717 | 768 | 93 | |

| 2013 | 734 | 778 | 94 | |

| 2014 | 762 | 791 | 96 | |

| 2015 | 813 | 809 | 100 | |

| 2016 | 859 | 832 | 103 | |

| 2017 | 896 | 8860 | 104 | |

| 2018 Q1 | 954 | 881 | 108 | |

| 2018 Q2 | 951 | 876 | 109 | |

The monhtly CPI report also includes two measures of inflation in rents. The CPI for actual rent (blue) continued an apparent slow deceleration, while owner's equivalent rent (red), the major component of inflation, remains near the highest levels in a decade, at over 3% YoY:

HUD's Rental Affordability Index

Yet another metric is HUD's Rental Affordability Index which, similarly to my chart above, compares median renter income with median asking rent. In its most recent (Q1) uupdate, it, like the median household income data, shows both rents and renters' income bottoming out in 2011-12, but with rents outpacing income ever since:

As a result, the trend in "rental affordability index," according to HUD, which had been easing since 2011, has declined in the past year to matchits worst levels:

.

Note that HUD's measure of housing affordability also generally deteriorated in 2017, making home-buying the least affordable since 2008, although better than during the bubble years.

But the strong suggestion is that, as housing has become less and less affordable, more households are forced into renting, which has responded by *also* becoming less affordable.

[Paranthetically, I'm not sold on HUD's method, mainly because it relies upon annual data released with a lag. In other words, the entire last year plus is calculated via extrapolation.]

Rent Cafe's monthly rental index

Rent Cafe's monthly rental index

Finally, there is a monthly rental index calculated by Rent Cafe. This has the benefit of being much more timely. Since it is not seasonally adjusted, the index must be compared YoY. While Zumper only includes 12 months of data in their monthly releases, at the beginning of this year they did publish the historical YoY record of their index (blue in the graph below). Rent Cafe's measure of rent shows that a surge to over 5% increases YoY occurred in 2015 and early 2016, and has abated to less than 4% YoY since, in contrast to the CPI measures and also to HUD's and the Census Bureau's data:

Through 2017, their measure of rents was continuing to grow at about 3% YoY. Below are the last 12 months through July:

Here's the bottom line, from all 4 sources: regardless of which measure we use, rents are growing faster than nominal wages for nonmangerial workers,which have onl increased at 2.7% YoY through last month.

In particular, this quarter's Census report not only indicates no relief from the "rental affordability crisis," it, like all the other metrics, shows that it is becoming worse, as -- most likely -- more and more households are being shut out of the home-buying market due to 5%+ YoY increases in house prices and increased interest rates, and are forced to compete for apartments instead.

In particular, this quarter's Census report not only indicates no relief from the "rental affordability crisis," it, like all the other metrics, shows that it is becoming worse, as -- most likely -- more and more households are being shut out of the home-buying market due to 5%+ YoY increases in house prices and increased interest rates, and are forced to compete for apartments instead.

Saturday, August 11, 2018

Weekly Indicators for August 6 - 10 at Seeking Alpha

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at Seeking Alpha.

Two long leading indicators are within 1% of turning negative. And two short leading indicators are also weakening considerably.

A friendly reminder that not only is the post informative, but I get compensated the more people read it, so by all means please read it!

Friday, August 10, 2018

Real wages decline YoY, while real aggregate payrolls grow

- by New Deal democrat

With the consumer price report this morning, let's conclude this weeklong focus on jobs and wages by updating real average and aggregate wages.

Through July 2018, consumer prices are up 2.9% YoY, while wages for non-managerial workers are up 2.7%. Thus real wages have actually declined YoY:

In the longer view, real wages have actually been flat for nearly 2 1/2 years:

Because employment and hours have increased, however, real *aggregate* wage growth has continued to increase:

Real aggregate wages -- the total earned by the American working and middle class -- are now up 25.8% from their October 2009 bottom.

Finally, because consumer spending tends to slightly lead employment, let's compare YoY growth in real retail sales, measured quarterly (red), with that in real aggregate payrolls (blue):

Here's the monthly close-up on the last 10 years:

Since late last year real retail sales growth has accelerated YoY, so we should expect the recent string of good employment reports to continue for at least a few more months.

Thursday, August 9, 2018

Four measures of wages all show renewed stagnation

- by New Deal democrat

This is something I haven't looked at in awhile. Since 2013, I have documented the stagnation vs. growth in average and median wages, for example here and here. I last did this in 2017. So let's take an updated look.

We have a variety of economic data series to track both average and median wages:

- The most commonly known measure is that of average hourly pay for nonsupervisory workers, which is part of the monthly jobs report.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which conducts the household employment survey, also reports "usual weekly earnings" for full time workers each quarter.

- The BLS also measures the Employment Cost Index quarterly.

- The BLS also measures "business sector compensation per hour" quarterly.

Let's start with nominal wages. The first graph below shows the YoY% growth in each of the four measures:

While each is noisy, the overall trends are clear:

- First, in this cycle as in the last, wage growth declined coming out of recessions, then rose as the expansion continued.

- Second, by most measures nominal growth has picked up somewhat in the last year.

- Third, secularly there has been an undeniable slowdown in wage growth, which (while not shown) was 4-6% in the late 1990s peak and 3-4% at the 2000s peak. So far in this expansion it is no better than 2.5%-3%. I believe this is in part due to how weak the employment situation was for so long into this expansion, but also secularly due to shifts in bargaining power, as employers learn over time that employees can be retained with lower and lower annual increases in compensation.

Now let's turn to the real, inflation-adjusted measures. Our first graph starts out normed to 100 for each measure in the fourth quarter of 2007.

After a spike during the Great Recession due entirely to the collapse of gas prices at that time, real wage growth declined through 2013 time frame, then rose significantly from late 2014 through early 2016 mainly due to the decline in gas prices. Since that time, 3 of the 4 measures (all except the ECI) have turned flat if not worse. Further, note the divergence between the mean measure of the average hourly earnings (blue) and median measures in usual weekly earnings (red) and the employment cost index (green), strongly suggesting that gains have been skewed towards the upper end of the income distribution.

Finally, let's look at the YoY% real growth in the four measures:

Here the picture continues to be not good at all. After growing 2-3% in real terms during 2014-15, in 2016 real wage growth decelerated to only 0.5%-1.5% across the spectrum of measures, and as of the most recent readings is between -0.5% to +0.5% .

In my last look at this data over a year ago, I concluded that the prospects for further meaningful wage growth for the broad mass of American workers during this cycle was dim. Nothing that has happened since that time has changed this poor result. What little nominal acceleration in gains there has been in any of the four series has been entirely negated by inflation. What gains in income have been made at the household level appear to be due exclusively to declines in the unemployment and underemployment rates.

Wednesday, August 8, 2018

June 2018 JOLTS report evidence of both excellent jobs market and taboo against raising wages

- by New Deal democrat

Yesterday's JOLTS report remained excellent, suffering only in comparison to last month:

- Hires were just below their all-time high of one month ago

- Quits were just below their all-time high of one month ago

- Total separations made a new 17-year high

- Openings were just below their all-time high of two months ago

- Layoffs and discharges rose to their average level over the past two years

In short, the JOLTS report for June confirmed the excellent employment report of one month ago.

So let's update where the report might tell us we are in the cycle, remaining mindful of the fact that we only have 18 years of data.

So let's update where the report might tell us we are in the cycle, remaining mindful of the fact that we only have 18 years of data.

Let's start with the simple metric of "hiring leads firing." Here's the long term relationship since 2000, quarterly:

Here is the monthly update for the past two years measured YoY:

In the 2000s business cycle, hiring and then firing both turned down well in advance of the recession. Both are still advancing through the end of the second Quarter this year, and their YoY strength has rebounded.

In the 2000s business cycle, hiring and then firing both turned down well in advance of the recession. Both are still advancing through the end of the second Quarter this year, and their YoY strength has rebounded.

In the previous cycle, after hires stagnated, shortly thereafter involuntary separations began to rise, even as quits continued to rise for a short period of time as well. Here's what that looks like quarterly through midyear 2018 (note: involuntary separations are inverted, and quits are multipiled *2 for scale):

Unlike the 2000s cycle, it looks like involuntary separations may have already made their low for this cycle, while both hires and quits are still increasing. This in no way looks like a late-cycle report.

Finally, let's compare job openings with actual hires and quits. As you probably recall, I am not a fan of job openings as "hard data." They can reflect trolling for resumes, and presumably reflect a desire to hire at the wage the employer prefers. In the below graph, the *rate* of each activity is normed to zero at its June 2018 value:

Looked at this way, the data is very telling. While the rate of job openings is at an all time high, the rate of actual hires isn't even at its normal rate during the several best years of the last, relatively anemic, expansion. Meanwhile quits are tied for their best level since 2001 (at the end of the tech boom).

In other words, in econospeak, "wages are sticky to the upside." In everyday language, there is an employer taboo against raising wages. In response, employees are reacting by quitting at high rates to seek better jobs elsewhere.

In short, the June JOLTS report confirms a thriving employment market, but a market that is not in wage equilibrium, as employers are failing to offer the wages that employees demand to fill openings.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)