- by New Deal democrat

No economic news of note today or tomorrow, except the (very late) Q3 Senior Loan Officers Report this afternoon, which will tell us about the state of credit, but is anticipated in much more timely - i.e., weekly - fashion by the Chicago Fed’s Financial Conditions Index.

So let’s take a look at some noteworthy items from last Friday’s jobs report.

As I headlined my blurb on Friday, this report continued the process of deceleration. In fact, we had the lowest amount of jobs growth since the pandemic lockdowns with the exception of December 2020:

And, to reiterate for the umpteenth time, consumption leads jobs. One good point I’ve seen others make, and is well taken, is that this year consumption has switched over from goods (Amazon et al delivering to your door) to services. Here’s a look at both, normed to 100 just before the pandemic hit:

You can see that retail spending boomed, especially after the 2021 stimulus, and has since declined somewhat, while the broader measure of consumer spending has continued to increase, at a slower pace.

Since real personal consumption expenditures is the flip side of the coin of real retail sales, but more broadly includes services spending, here’s a historical look of the YoY% change in that (/2 for scale) vs. payrolls:

Just like real retail sales, it has done a good job anticipating the near term changes in job growth.

Now here is the same metric for real retail sales (blue), real personal consumption expenditures (gold), and jobs (red) since just before the pandemic:

As noted in the first graph above, job growth has been slowing down, but not yet to the level of either of the measures of consumption. But it’s slowly getting there.

Another point I made last week several times is that jobless claims lead the unemployment rate. Here’s the updated graph of that relationship with Friday’s increase in unemployment added:

We’re probably now at the unemployment rate most consistent with the recent small rise in jobless claims.

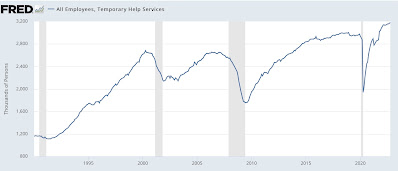

There are several other leading indicators in the jobs report. One is temporary hiring:

In the past, a downturn has started a number of months before any recession. That isn’t at all the case here.

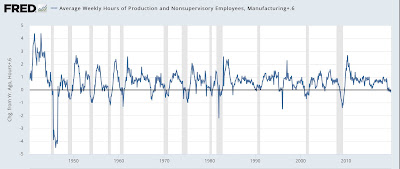

Another leading indicator is the number of hours in the average manufacturing work week. Manufacturing tends to turn down before services, and typically hours get cut before layoffs occur. In the past the recession threshold has been a decline of -0.6 hours YoY:

At present, there has been a decline of as much as -0.4 hours, and presently -0.2 hours, so not yet quite at the level indicating an oncoming recession:

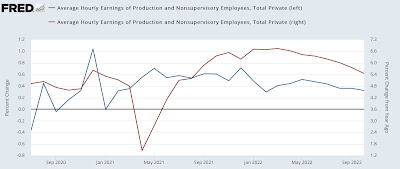

Turning from leading indicators to inflation concerns, i.e., wage growth, this has also decelerated. Below I show the monthly % change in wages (blue) vs. the YoY% change (red) for non-supervisory workers:

Wage growth has continued, but at a steadily decelerating rate for nearly a year. By way of comparison, in 2018 and 2019 wage growth averaged 3.3% annually, vs. 5.5% for the past 12 months vs. a peak of 6.7% past May.

Finally, real aggregate payrolls for non-supervisory workers (essentially, total real compensation for the working and middle classes) is an excellent coincident marker for the onset of recessions. Here’s the historical record for the past nearly 60 years:

This is an almost perfect indicator. There are no false positives, except possibly the 2002-03 near double-dip. And there are no false negatives either. In other words, if the rate of YoY inflation starts to exceed the rate YoY aggregate payroll growth, you are within a month or two before or after the onset of a recession, period.

As of September, payroll growth exceeded inflation by 1.1%. We know that payrolls growth slowed in October. We’ll find out about inflation later this week.

To sum up: on Friday I wrote that the jobs report showed deceleration and deterioration, which it certainly did. On the other hand, deceleration and deterioration don’t mean an actual downturn - and we’re not there at this point. But the long leading indicators, as well as consumption, have been screaming for months to expect more deterioration, and we should.