- by New Deal democrat

Seasonally adjusted consumer prices rose 0.4% in February. As a result, over the past several months there has been a significant uptick in YoY inflation to 1.7% from 1.1% in November.

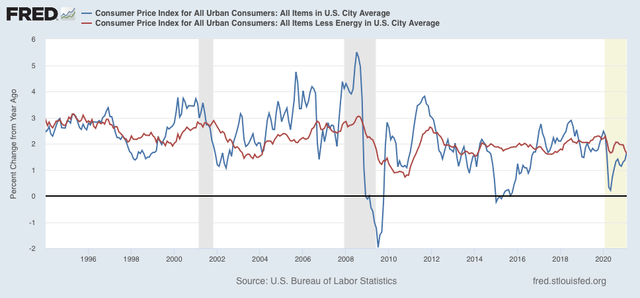

Aside from the pandemic, for the past 40 years, recessions had happened when CPI less energy costs (red) had risen to close to or over 3%/year, usually driven by increases in the price of oil by more than 40% YoY:

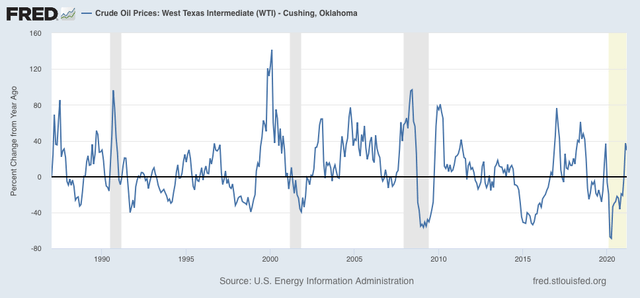

Despite recent increases in the price of oil, now up 30% YoY as shown in the graph below, as of this month CPI less energy is only 1.6%, showing no real price pressure at all:

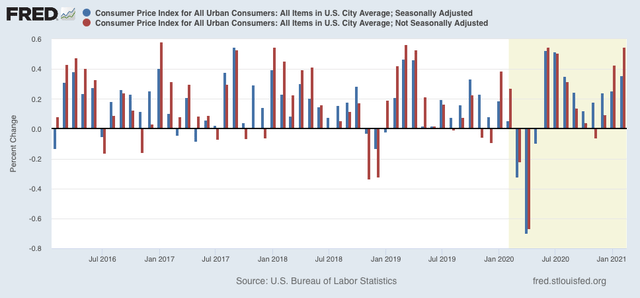

Because pandemic affects are probably influencing seasonality, below I show both the m/m adjusted and non-seasonally adjusted change in CPI:

Here are the non-seasonally adjusted m/m% increases in prices in February for the past 5 years:

2016 +.1%

2017 +.3%

2018 +.5%

2019 +.4%

2020 +.3%

This February the non-seasonally adjusted m/m% increase was +.6%, the highest since 2005. An increase in inflation, as vaccinations take hold, the pandemic ebbs, and ever increasing numbers of people resume close to normal lives - meaning increased demand for things like travel and entertainment activities - is very likely, but unless there is a much more meaningful increase in the cost of energy, I do not see any significant cause for concern.

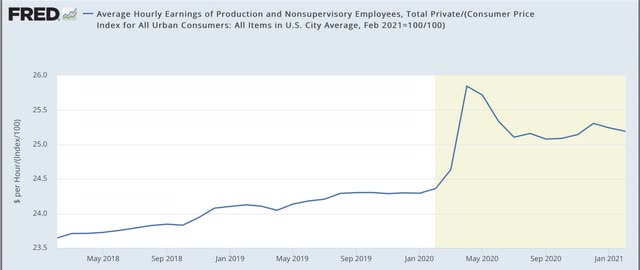

Now let’s take a look at how inflation has affected real wages. Because wages are “stickier” than prices, typically as recessions beat down prices (or at least price increases), in real terms wages rise, either during or just after a recession. That has been the case for the coronavirus recession as well. It is the “real” buying power of wages among those still securely employed during a recession that is one of the engines that usually restarts growth.

Real wages declined -0.2% in February, and are -2.5% off their all-time high last April. Since last June they have been in a narrow range of -2% to -3% off that peak. Much of the volatility over the past year, of course, has been as a result of the skew in layoffs, which have disproportionately affected those in low-wage leisure and entertainment industries:

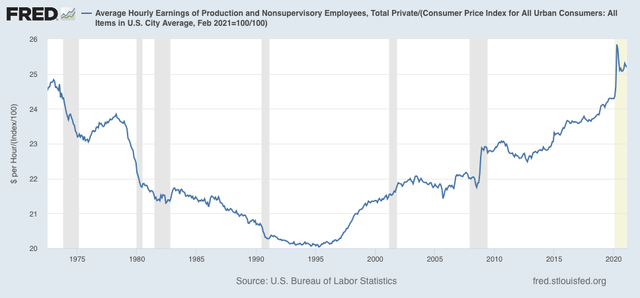

Here is the longer-term view, showing that current real wages remain above their previous 1973 peak:

A further decline in real wages as these workers are called back to employment is quite likely. That would be in accord with history, as real wages are a long lagging metric, that tend to increase long after an economic recovery has begun, and un- and under-employment fall to rates where employers must compete for relatively scarce workers.