- by New Deal democrat

First of all, let me join in full in the following from Calculated Risk:

These are not normal times, and I can't just post economic data and remain silent on other issues.

Mr. Trump's executive order is un-American, not Christian, and hopefully unconstitutional. This is a shameful act and no good person can remain silent.

I believe that the sheer heartlessness of Trump's Order is a feature, not a bug. It is designed for maximum media coverage in order to show his supporters that he is delivering on his promises.

It is likely that in a longer timeframe this will backfire, as the cruelty of separating families, turning away children, and refusing entry to people who already had legal permission to live here via visas and even green cards, turns people against Trump and his enablers.

Once upon a time, for academic reasons I read the same book that Trump was rumored to have by his bedside in NYC: the english translation of the full text of Adolf Hitler's speeches. Hitler's argument for getting ordinary Germans to go along with his extreme anti-Semitic agenda was masterful. It went in essence like this: "I know that there are a very few good Jews, and you may know a few of them. But the vast majority of Jews, who you don't know, are evil. In order to get rid of the vast majority of evil Jews, we have to sweep up a few of the good ones. So don't worry, we will take care of it." By getting people to overlook their own experience with Jews they knew, he prevailed.

In contrast - for example - gay rights triumphed when enough people knew gays in their ordinary lives, and realized that they were no different from anybody else. So they were unable to see any valid reason to discriminate against them.

This ban is much more like the second situation than the first. Hitler argued that he might have to inflict hardship on a few good people in order (allegedly) to get to the mass of bad apples. Trump is inflicting a lot of harm on a mass of good people in order (allegedly) to get to a few bad apples.

And we haven't even gotten to the point yet when the same heartlessness is going to be inflicted on DREAMers.

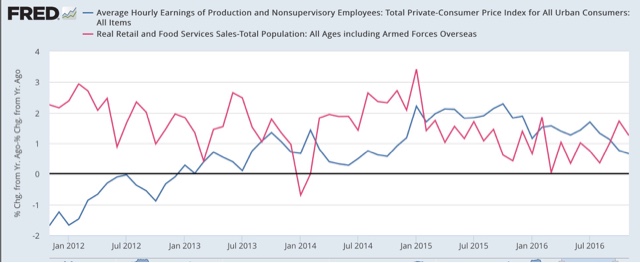

Second, a few days ago I pointed out that economic confidence has actually spiked again in the week after Trump's inauguration. But that does not appear to be translating into actual spending so far. In fact it is possible that the opposite is happening.

Here is a look at Gallup's economic confidence measure since its inception:

See that big downward spike in 2011? That's the debt ceiling debacle, where Congress threatened to default on debts the US had already incurred. Lots of economic data headed south at the same time, leading to ECRI saying (incorrectly) that a recession was imminent.

But consumer spending by Gallup held up throughout. Notice the *absence* of any observable movement in 2011 in that measure:

That consumers told Gallup they were still spending as before was my first sign that ECRI was wrong.

Now here is that same consumer spending graph over the last two years:

If you don't see any substantial upward movement particularly at the end, you would be correct. Consumer spending is very seasonal, with a big peak in the Christmas season, and a smaller bounce for back-to-school sales.

While December spending by consumers was up YoY, so far January is flat.

http://www.gallup.com/poll/201584/consumers-set-nine-year-high-december-spending.aspx

So while there has been a big spike in confidence (very partisan, as GOP confidence has risen more sharply than the decline shown by Democrats), so far it appears not to have translated into conviction via actual spending.