Saturday, February 3, 2018

Weekly Indicators for January 29 - February 2 at XE.com

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at XE.com.

Not surprisingly, stocks and bonds took center stage this week.

Friday, February 2, 2018

January jobs report: good headline growth, mostly negative internals. UPDATE: THE BOSSES GAVE THEMSELVES A RAISE

- by New Deal democrat

HEADLINES:

- +200,000 jobs added

- U3 unemployment rate unchanged at 4.1%

- U6 underemployment rate rose 0.1% from 8.1% to 8.2%

Here are the headlines on wages and the chronic heightened underemployment:

Wages and participation rates

- Not in Labor Force, but Want a Job Now: declined -137,000 from 5.308 million to 5.171 million

- Part time for economic reasons: rose +74,000 from 4.915 million to 4.989 million

- Employment/population ratio ages 25-54: fell -0.1% from 79.1% to 79.0%

- Average Weekly Earnings for Production and Nonsupervisory Personnel: rose +$.0.03 from $22.31 to $22.34, up +2.4% YoY. (Note: you may be reading different information about wages elsewhere. They are citing average wages for all private workers. I use wages for nonsupervisory personnel, to come closer to the situation for ordinary workers.)

Holding Trump accountable on manufacturing and mining jobs

Trump specifically campaigned on bringing back manufacturing and mining jobs. Is he keeping this promise?

Trump specifically campaigned on bringing back manufacturing and mining jobs. Is he keeping this promise?

- Manufacturing jobs rose by +15,000 for an average of +17,300 a month vs. the last seven years of Obama's presidency in which an average of 10,300 manufacturing jobs were added each month.

- Coal mining jobs increased by 100 for an average of -46 a month vs. the last seven years of Obama's presidency in which an average of -300 jobs were lost each month

The more leading numbers in the report tell us about where the economy is likely to be a few months from now. These were mixed.

- the average manufacturing workweek fell -0.2 hour from 40.8 hours to 40.6 hours. This is one of the 10 components of the LEI.

- construction jobs increased by 36,000. YoY construction jobs are up +226,000.

- temporary jobs increased by +1,800.

- the number of people unemployed for 5 weeks or less increased by +45,000 from 2,235,000 to 2,280,000. The post-recession low was set over two years ago at 2,095,000.

Other important coincident indicators help us paint a more complete picture of the present:

- Overtime was unchanged at 3.5 hours.

- Professional and business employment (generally higher- paying jobs) increased by +23,000 and is up +448,000 YoY.

- the index of aggregate hours worked in the economy rose by +0.2%.

- the index of aggregate payrolls rose by +0.4% .

Other news included:

- the alternate jobs number contained in the more volatile household survey increased by +409,000 jobs. This represents an increase of 2,354,000 jobs YoY vs. 2,114,000 in the establishment survey.

- Government jobs rose by 4,000.

- the overall employment to population ratio for all ages 16 and up is unchanged at 60. m/m and is up + 0.2% YoY.

- The labor force participation rate is unchanged at 62.7 m/m and is down -0.2% YoY at 62.7%

SUMMARY

This was a very mixed report. The headline jobs number was very good, but most of the internals were flat to negative, including an uptick in the underemployment rate, a decline in the manufacturing workweek, and a decline in prime age labor participation. Short term unemployment also increased slightly.

And of course, wage growth for non-managerial personnel continued to be somnolent.

So while we have a recent increase in employment growth, most of the other measures are either tepid or are fraying a little bit around the edges.

UPDATE: I see where the main item in most other discussions in this report is "the big jump in wages!

Ummm, not so fast. The "big raise" of 2.9% YoY is for ALL employees, including the bosses. The number for workers who aren't managers, as I report above, is a tepid 2.4%, right about where it has been for several years. So it workers got 2.4% YoY, but workers plus bosses got 2.9% YoY, then that means the bosses gave themselves big fat raises that have not been shared with the line workers.

I'm not impressed.

UPDATE: I see where the main item in most other discussions in this report is "the big jump in wages!

Ummm, not so fast. The "big raise" of 2.9% YoY is for ALL employees, including the bosses. The number for workers who aren't managers, as I report above, is a tepid 2.4%, right about where it has been for several years. So it workers got 2.4% YoY, but workers plus bosses got 2.9% YoY, then that means the bosses gave themselves big fat raises that have not been shared with the line workers.

I'm not impressed.

Thursday, February 1, 2018

About that Trump wage boom

- by New Deal democrat

Over last weekend, I read a bunch of notes which indicated that Trump was claiming credit for a boom in wage growth.

Let's take a look:

THIS is a wage boom:

In the 1960s, real wages grew by almost 9% over 7 years, anaverage of 1.3% per year.

THIS is also a wage boom:

In the late 1990s, real wages grew by just over 9% in 7 years, again averaging 1.3% per year.

This is NOT a wage boom:

During the first year of Trump's term, real wages grew by 0.6%. This is less than half of the rate of a real wage boom.

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

What's behind the big Q4 decline in real median weekly wages?

- by New Deal democrat

[Note: This is a post I was working on last week. I hypothesized that the employment cost index would validate the analysis. Well, I didn't get around to posting it, and the ECI came out this morning. So, how did I do? ]

Last week the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that real weekly median wages declined by over 2% in the 4th quarter of last year! This is quite the anomaly in the face of generally good data that has been reported in the last few months.

Dean Baker put it in context, noting that for the year 2017, real weekly median wages rose signficantly over 2016:

But I thought I would dig deeper to see why the anomaly had occurred. So I took a detailed look at each of the three qualifiers: "real," "median," and "weekly." Where did the dowturn come from?

Well, part of it certainly had to do with inflation. Recall that one of my favorite measures, "real aggregate wages" actually peaked in July and has declined -0.8% since then, mainly due to an uptick in inflation. It is easy to break that out, since the BLS also releases nominal weekly wage data. So here are the two together for comparison:

The uptick in inflation is responsible for about 1/3 of the decline in real weekly median wages.

Next, let's take a look at average hours worked per week:

These actually increased between the 2nd and 4th quarters. So it's not that fewer hours are being worked per week.

Is something going on with the "median" vs. "average" measures? The next graph compares the weekly measure with real average hourly wages:

Median wages declined more than average wages. So that tells us that the main thing that probably happened had to do with the makeup of the labor force.

To check that, I compared job growth among professional and business workers (a high-paying category) vs. retail workers (a low-paying category). How much did each grow during recent quarters? Here's what I found:

Eureka! Professional and business hiring has remained fairly steady, even having a small bump in the second quarter. But the retail apocalypse manifested itself by outright declines in the 3rd and especially second quarters, vs. flatness in the 4th.

It appears the actual outliers were those two quarters rather than the 4th quarter. The downturn in low paying retail jobs in the middle quarters of 2017 made the median 50th percentile worker someone who worked in a somewhat higher paying job.

The best way to test this hypothesis is to see what happened quarter over quarter to pay for identical jobs. That is exactly what gets measured by the Employment Cost Index. If what mainly happened in the 4th quarter is that the mix of jobs in the economy changed, then the only decline we should see in the E.C.I. is that due to inflation. That report comes out next week, so we will have the answer soon enough.

----

AAAAND, this morning the Employment Cost index showed that wages *ROSE* 0.5% in Q4, and total compensation rose 0.6%. The nominalYoY% increase for each was 2.5%:

In real, inflation adjusted terms both wages median compensation declined -0.3%:

So the big dropoff in weekly median wages does indeed appear to be a story of a change in the mix of jobs, rather than a drop in actual pay of a job. Still, nominal wage growth in the latter part of 2017 was eclipsed by the uptick in inflation. This, by the way, adds to the evidence that the increase in consumer spending in the last few months has been driven by the wealth effect (increasing house and stock prices for the affluent and wealthy) and dipping into savings for everybody else.

----

AAAAND, this morning the Employment Cost index showed that wages *ROSE* 0.5% in Q4, and total compensation rose 0.6%. The nominalYoY% increase for each was 2.5%:

In real, inflation adjusted terms both wages median compensation declined -0.3%:

So the big dropoff in weekly median wages does indeed appear to be a story of a change in the mix of jobs, rather than a drop in actual pay of a job. Still, nominal wage growth in the latter part of 2017 was eclipsed by the uptick in inflation. This, by the way, adds to the evidence that the increase in consumer spending in the last few months has been driven by the wealth effect (increasing house and stock prices for the affluent and wealthy) and dipping into savings for everybody else.

Tuesday, January 30, 2018

Monday, January 29, 2018

Is the economy partying like it's 1999?

- by New Deal democrat

Suddenly I have a lot to say about the economy. My sense is that we are on to a new phase after the 2015 shallow oil-patch centered recession and 2016-17 rebound. The data has a feel to it of a late cycle blowoff.

Let's start with this morning's personal income and spending. In the last 4 months, personal consumption expenditures, like retail sales, have taken off:

Typically after mid-cycle personal consumption expenditures outpace retail sales (10 of the 11 previous cycles, to be precise). This is so regular that it is a primary mid-cycle indicator for me.

Well, as you can see, in the last 4 months, retail sales have come roaring back, even compared with PCE's. But if you cast your eyes to the left edge of the graph, you can see the tail end of the same phenomenon in 1999. Although I haven't posted the nominal (vs. inflation adjusted) numbers, the same thing happened in the late 1990s. In 1999, both retail sales and PCE's accelerated, but retail even more than PCE'S. When the stock market peaked at the beginning of 2000, both started declining rapidly, culminating in a recession 15 months later.

That we might be entering a blowoff stage is confirmed by the personal saving rate, as shown below:

Rapid declines in this rate tend to happen after mid-cycle. On the one hand, they are signs of economic confidence, as consumers are willing to go further out on a limb with finances. On the other hand, the lower savings rate leaves consumers vulnerable to future shocks.

In 1999, the blowoff was highlighted by the wealth effect. The recent melt up in the stock market may be energizing the same behavior. In particular, soaring consumer confidence in the last 4 months is concentrated on GOPers:

Even democrats feel a little more confident, and independents significantly more so. In 2013, the situation was reversed, where it looked like increased spending was powered by confident democrats (GOPers thought we were in the abyss).

Another facet of the data that suggests a blowoff might be underway is the surge in interest rates. Below is a graph of 2-, 10- and 30 year rates since just before the presidential election:

As of this morning, 2 year rates are 2.14%, and 10 year rates are above 2.70%, a nearly 4 year high.

I don't profess any insight as to whether interest rates will continue to rise or not, but it is interesting that the 30 year bond has not broken out of its high one year ago.

Which brings me to the point that, like gas, the cure for high interest rates is -- high interest rates.

Here's a graph of 30 year mortgage rates:

Like the 30 year bond, these have not made a new 1 year high. As of this morning, conventional 30 year mortgage rates are 4.28%, about 0.10% below their 52 week high of 4.38%.

Housing stalled for several quarters last year in the face of aa 1% increase in mortgage rates, and slowed down even more in 2014 when mortgage rates rose 1.4% off their bottom. If mortgage rates hit 4.4% and stay above that level for several months, I expect another housing slowdown to begin, although given the demographic tailwind from the Millennial generation, I wouldn't expect an outright downturn in housing unless mortgage rates rise all the way to about 5%.

Housing stalled for several quarters last year in the face of aa 1% increase in mortgage rates, and slowed down even more in 2014 when mortgage rates rose 1.4% off their bottom. If mortgage rates hit 4.4% and stay above that level for several months, I expect another housing slowdown to begin, although given the demographic tailwind from the Millennial generation, I wouldn't expect an outright downturn in housing unless mortgage rates rise all the way to about 5%.

In other words, it is probably OK to party like it was 1999. There wasn't a recession until 2001, and this blowoff isn't likely to give way to a recession in the immediate future either.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Weekly Indicators for January 22 - 26 at XE.com

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at XE.com. Aside from more mixed long leading indicators, there has been this anomalous decline in rail and steel.

Friday, January 26, 2018

Leading components of Q4 GDP forecast continued growth in 2018

- by New Deal democrat

This morning's release of Q4 2017 GDP was in line with estimates, rising 2.7% on a preliminary basis. As usual, my attention is focused less on where we *are* than where we *will be* in the months and quarters ahead.

There are two leading components of the GDP report: real private residential investment and corporate profits. Because the latter will not be released until the second or third revision of the report, I make use of proprietors' income as a more timely if less reliable placeholder.

So let's take a look at each.

The news on real private residential fixed investment was mixed. Measured both by itself (blue), and by the more precise method of its share of the GDP as a whole (red), residential investment rose. But although it came close, it has not made a new high since three quarters ago:

Together these are pretty strong evidence that the economy will continue to expand through the rest of 2018.

One final note: although the GDP reports have been good for the last three quarters, I'm not expecting any big positive breakout. This goes back to the relative flatness or restrained growth in housing. The below two graphs show the leading relationship between housing permits (using the less volatile single family measure) and GDP broken up into two roughly 30 year periods:

The YoY% change in permits for the last 3 years has been roughly 10% (divided by 4 for purposes of scale in the above graphs shows a number of ~2.5%). While there is certainly not a 1:1 relationship in the numbers, continued roughly 2.5% YoY growth of GDP for the next few quarters is a reasonable projection.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

Housing: sales and prices accelerate in Q4 2017

- by New Deal democrat

With the exception of rental vacancies and pricing, which should be released next Tuesday, with the morning's release of new home sales we now have a good look at the very forward-looking housing market through the end of 2017.

Both sales and prices have started to accelerate. This post is up at XE.com.

Wednesday, January 24, 2018

A note on December existing home sales

- by New Deal democrat

First of all, sorry for the light posting this week. There's not much news until tomorrow and Friday, and yesterday was a travel day. So.....

While existing home sales are about 90% of the entire housing market, they are the least important economically, because of their much more limited impact since they do not involve any new construction.

That being said, December's existing home sales, at 5.57 million annualized, were only 1% above last December's pace. First and foremost, that's a matter of higher mortgage rates this year. In fact, mortgage rates haven't made a meaningful new low since 2013 -- although they briefly neared that low in late 2016 -- and that has shown up in a gradual deceleration of the pace of sales since that time, as show by Bill McBride's graph below:

Here is a close-up of the last three years from FRED, excluding today's report, which hasn't been posted yet:

Here's the same data YoY, compared with housing starts in red, averaged quarterly to cut down on the volatility:

The same pattern of decelerating growth is shown in both series.

Although sales turn before either prices or inventory, the consistent price increases and lack of inventory are playing a role in this deceleration, contra which is the demographic tailwind.

Tomorrow the more important, and leading (but very volatile) new home sales report will be released. I am expected a significant downward revision in November's blowout number.

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

Recent increased interest rates probably won't derail housing

- by New Deal democrat

In the last couple of weeks, long term interest rates have moved significantly higher. As of yesterday, the 10 year bond closed at roughly 2.66%, its highest yield in 3 1/2 years. If this move is sustained for a few months, I expect it to have an effect on the housing market, but how much?

Here is an updated variation on a graph I have run many times over the last 5 years: the YoY change in the 10 year treasury bond, inverted (blue), versus the YoY% change in housing permits for single family homes (green). I'll explain the red line below:

In general, the housing market responds first and foremost to interest rates. So when interest rates rise (shown as a negative YoY in the graph), permits historically have fallen.

But in this expansion, permits have responded by decelerating increases rather than by actual declines. A decent estimate is that the demographic tailwind of the large Millennial generation arriving at home-buying age is that it has added 7.5% growth YoY vs. what we would otherwise expect. That is what is shown by the red line in the graph above.

I still expect a few months of restrained *YoY* growth (not m/m, which has already increased to new highs) before improvement in that metric.

But the above graph does not show the uptick in rates this month, so the below is the same graph, limited to the last year, but with daily values in treasury rates:

The bottom line is that the recent increase in rates isn't enough to derail the housing market. I suspect that rates would have to go above their 2013 high of 3.03% for that to happen.

Finally, there is another factor to consider, which is monthly mortgage payments. As I pointed out several months ago, monthly mortgage payments got downright cheap at the bottom of the housing market, and still are quite reasonable compared with their 2005 highs. Here's an update graph of real, inflation-adjusted mortgage payments from Core Logic:

This is probably also a factor in why housing has responded relatively tepidly to changes in interest rates. Especially with soaring rents and constrained supply, owning is -- relative to renting -- still a bargain. It will probably take another 10% increase in real monthly carrying costs for that to become at all comparable to its surge during the housing bubble.

Sunday, January 21, 2018

Saturday, January 20, 2018

Weekly Indicators for January 15 - 19 at XE.com.

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at XE.com.

The new 40 year low in jobless claims was overshadowed by the jump in interest rates.

Friday, January 19, 2018

The intensity of Fed rate hikes as a precursor to recessions

- by New Deal democrat

Between 1931 and the mid-1950s, the yield curve never inverted, and yet there were 5 recessions (1938, 1945, 1948, 1950, and 1954). In particular, the 1938 "recession within the depression" was one of the worst of the 20th century.

So in a low inflation and low interest rate environment, where the yield curve may not invert, are there other signals from the bond market that are reasonably reliable?

A month ago I noted that spreads between corporate bonds and government securities have a very spotting record during more deflationary eras.

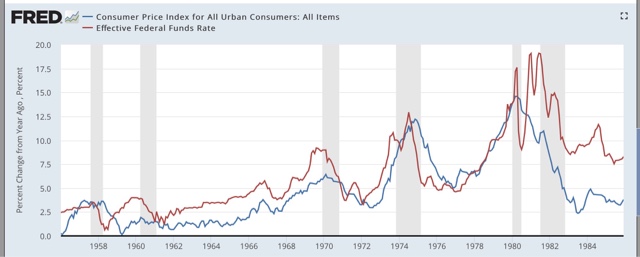

Today let's approach the issue from another angle. Is there something about the *intensity* of Fed moves that correlates with recessions? Below is a graph of the YoY change in the Fed funds rate since 1955, minus 1.5%, so that a YoY increase of 1.5% in the Fed funds rate = 0:

Twelve to eighteen months prior to 8 of the last 9 recessions, the Fed increased rates YoY by 1.5% or more.There were 4 false positives, two of which involved hikes of 1.5% or 1.75% (1962 and 1966), and one potentially false negative (a 1.5% increase in the Fed funds rate preceded the 1957 recession by 21 months). In the case of the false positives, there were slowdowns in GDP growth even though there was no outright recession.

So, in the most generous interpretation, a YoY Fed rate hike of 1.5% or more is almost certain to be followed by a slowdown, and more often than not by a recession. That's pretty decent even if not perfect.

That suggests that the very gradual Fed rate hikes of the last several years need not give us much concern. And indeed there is one (and only one) episode in the last 60 years that seems to bear this out. In the first half of the 1960s, the Fed gradually raised rates from 1% to 5% (blue line in the graph below):

These rate hikes coincided with economic growth of between 5% to 10% annually! Only when the Fed increased the pace of their hikes beginning in late 1965 did a slowdown occur, as shown by annualized real GDP in the graph below:

Of course, correlation is not causation, and one obvious candidate for causation is that the Fed is simply reacting to an increase in inflation either already underway or correctly anticipated. To check this, the below two graphs show the YoY% change in inflation, together with the YoY change in the Fed funds rates:

Indeed, with a few exceptions, sharp 1.5%+ increases in the Fed funds rate YoY tend to occur along with equally sharp increases in inflation.

But there are several exceptions, all having to do with the low interest rate environment.

In the first place, as recently as 2011, inflation rose from 1% to 3.8%. The Fed stood pat. No recession occurred.

Now let's take a look at the 1950s:

Here we have two completely different examples. In the period of 1954-57, the Fed hiked rates by a total of 2.25% while inflation went from negative to just under 4%. In contrast, during the inflationary 1960s-1980s period, the Fed raised rates by 2% or more multiple times without a recession ensuing.

In contrast, in the 1958-60 period, inflation remained under 2%, but the Fed aggressively raised rates from under 1% to 4%, and a recession ensured.

What we are left with is, even without looking at the yield curve, we can say that *either* a sharp rise in interest rates, *or* a sharp rise in inflation, almost always precedes to a slowdown, and more often than not precedes a recession. Right now, we have neither.

Thursday, January 18, 2018

A quick note on housing permits and starts

- by New Deal democrat

I'll do a more detailed analysis next week, once new home sales are reported, but for now a quick synopsis about December housing permits and starts:

- single family permits (the least volatile, most forward looking metric) made another new high

- total permits are just slightly below their October high

- the three month moving average of the more volatile housing starts made a new high save for the three month average from 10 months ago.

YoY interest rates are no longer a drag on the market, and I am impressed with the strength of the demographic tailwind. While not perfect, this was a very positive report.

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

Industrial production and retail sales both had strong 4th Quarters

- by New Deal democrat

Whether due to a bounce from hurricane interruptions, or some other reasons, both real retail sales and industrial production have now completed very strong 4th Quarters.

Together they point to a good GDP print next week.

This post is up at XE.com.

Monday, January 15, 2018

Minority unemployment: progress vs. prejudice

- by New Deal democrat

On this Martin Luther King Day, let's take a look at minority unemployment. This got a little attention earlier this month when the December jobs report showed the smallest gap ever between the unemployment rates of blacks and whites.

On this Martin Luther King Day, let's take a look at minority unemployment. This got a little attention earlier this month when the December jobs report showed the smallest gap ever between the unemployment rates of blacks and whites.

So let's start by confirming the good news. Indeed last month saw the smallest gap ever between the unemployment rates of the two groups:

The secular trend over the last 40 years has been very slow progress, as the relative low in unemployment from the early 1970s was superseded in the 1990s, which in turn was superseded by that of the 2000s, and now that too has been eclipsed. But of course, the black unemployment rate has for that entire time been higher than that for whites.

Next, let's compare black and Latino unemployment:

Similarly, for the entire forty year period, the rate of African American unemployment has been higher than that of Latino unemployment. What is most telling is that this metric hit a low point over 20 years ago. Since 1995 the proportion of Latino unemployment has decreased compared with black unemployment.

I believe this has had important political consequences. Like African American unemployment, the Latino unemployment rate has risen relative to white unemployment during and after recessions, and improved as expansions continues. Unlike black unemployment, however, Latino unemployment never blew out in the late 1970s and 1980s, and more strikingly, in both of this and the last expansion has come within 1.2% of white unemployment:

On the one hand, while we don't have any historical statistics that I am aware of with earlier immigrant groups, I suspect that Latinos hare having a typical immigrant experience: the first generation establishes the beachhead, and the second and thir d generations approach the employment norms of the majority natives.

But on the other hand, I think this has played a significant role in the backlash that gave us Donald Trump. Remember that the single issue which most changed in importance motivating voters between 2012 and 2016 was immigration:

On the one hand, while we don't have any historical statistics that I am aware of with earlier immigrant groups, I suspect that Latinos hare having a typical immigrant experience: the first generation establishes the beachhead, and the second and thir d generations approach the employment norms of the majority natives.

But on the other hand, I think this has played a significant role in the backlash that gave us Donald Trump. Remember that the single issue which most changed in importance motivating voters between 2012 and 2016 was immigration:

Considering that employment in smaller metro areas and rural ares has not grown so strongly during this expansion, and especially bearing in mind that roughly 1/4 of the Latino population (about 12 million of 48 million) are undocumented workers or illegal aliens, depending on your preference, I suspect that the ethnic backlash by Trump voters and the relatively good performance of Latino vs. white unemployment is not a coincidence.

Finally, in view of the continued difference between black and white unemployment rates, I wanted to take a look at how that breaks down by education, since the disparity in college educations may be one reason for the difference in in the rates.

But that isn't the case. Here are two separate graphs of unemployment, one of which also includes Latinos and Asians, and the other of which brakes down education by 5 levels:

When we consider that even with a conquerable education, the rate of black unemployment is still above that of Latino unemployment, and that black college graduates have an unemployment rate equivalent to that of whites who don't even have an associates degree, I am afraid that racial prejudice still plays a role in the jobs market.

Sunday, January 14, 2018

Saturday, January 13, 2018

Weekly Indicators for January 8 - 12 at XE.com

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators post is up at XE.com.

This week a lot of the data was affected by holiday seasonality, because it was for the week of New Year's Day.

Friday, January 12, 2018

Real wages in 2017

- by New Deal democrat

Now that we have the report on consumer prices for December, let's take a look at what happened with real wages in 2017.

Consumer prices increased +0.1% in December, and wages for non-managerial workers rose 0.3%, This for that month the average worker earned 0.2% more.

For the year, the nominal wages of non-managerial workers rose 2.4%, while prices increased 2.1%, meaning that for the entire year workers saw a whopping 0.3% increase in real pay:

Consumer prices increased +0.1% in December, and wages for non-managerial workers rose 0.3%, This for that month the average worker earned 0.2% more.

For the year, the nominal wages of non-managerial workers rose 2.4%, while prices increased 2.1%, meaning that for the entire year workers saw a whopping 0.3% increase in real pay:

Here's a close-up of the last 5 years:

But because inflation accelerated slightly in the second half of the year, and nominal pay increases slackened, real pay has actually decreased roughly -0.8% since peaking in July, and is barely up at all over the last 24 months.

Next let's take a look at the real aggregate pay that non-managerial workers earned in 2017. I like this measure because it tells me how much the economy as a whole has delivered to the middle and working class during the economic expansion. Here's the graph:

For the entire expansion, real aggregate pay has increased ~23%. On a YoY basis, aggregate real payrolls increased about 2.5%, about the average for this expansion:

In other words, consumers have more money in the aggregate, but only because the number of hours and jobs in the economy has increased, and almost not at all because their individual hourly pay increased in real terms in 2017.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)