(1) Real retail sales bottom and turn.

(2) Initial Jobless claims turn.

(3) The ISM manufacturing index turns above 50, i.e., signals actual growth.

(4) Industrial Production turns.

(5) ISM manufacturing index is above 53, ISM employment is at -5 or above, initial jobless claims are at least a sustained 16%-20% off peak, and both Industrial Production and Real retail sales have advanced at a rate of 2.5% or more year-over-year from the bottom.

By September, (1) through (4) had already happened. Number (5) is all about the strength of the turns. ISM and Real retail were already on the cusp of their final signals, and industrial production was growing, but not quite enough yet. Initial jobless claims were still only 15% or so off peak, dropping so slowly that it would take at least 3 more months at that rate to signal job growth.

I concluded with a prediction that payrolls would most likely hit bottom and turn around in November or December, +/- 1 month. How is that playing so far?

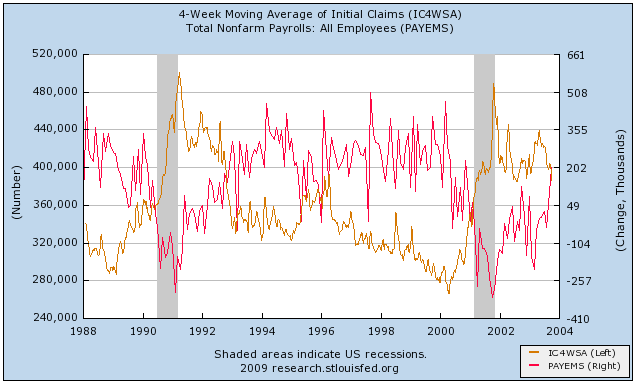

I. Initial Jobless Claims

In the first installment of the series, I looked at initial jobless claims. I noted that (1) in those recessions and recoveries where jobless claims fell steeply, peak unemployment occurred within 2 months of the point where jobless claims fell 12% from the peak; but (2) in those recessions and recoveries where jobless claims fell slowly, peak unemployment occurred not at the 12% mark, but only when new jobless claims were more than 16% less than peak claims, and stayed more than 16% off for at least 3 months thereafter.

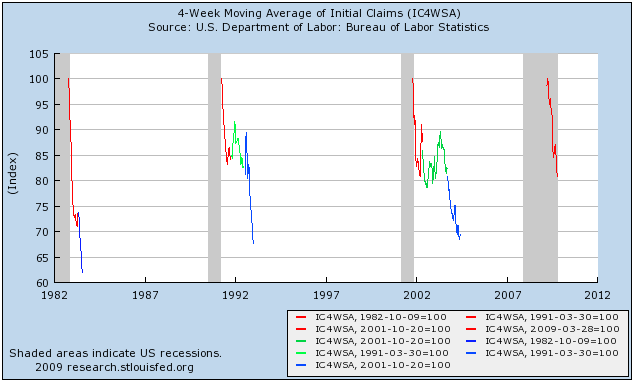

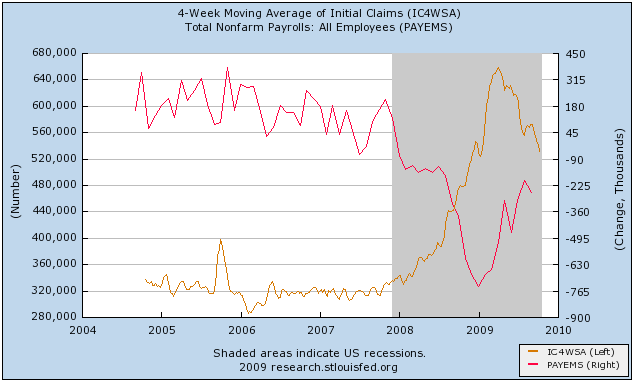

A month ago, initial claims were still less than 16% off their highs. That all changed in the last four weeks. Jobless claims have fallen substantially, and now the 4 week moving average stands at 531,500, almost 20% off the peak of 658,750, 6 1/2 months ago. Here is a graph comparing this recession with the two previous "jobless recoveries" and the V shaped deep recession of 1982 in terms of initial jobless claims:

In the graph above, the red lines represent the first 6 1/2 months off the peak of claims. As you can see, our recession/recovery is more comparable to the last two than to the 1982-3 recovery. The green lines represent the continuation of the "jobless recoveries" until the point where both jobs and the unemployment rate had bottomed. As you can see, jobless claims failed to penetrate the 20% off level except for a brief instance in summer 2002 (coinciding with a brief positive jobs number). There is no green line for 1983, because in that recovery payrolls immediately improved. The blue lines show how jobless claims dropped after both payrolls and unemployment reached their nadir.

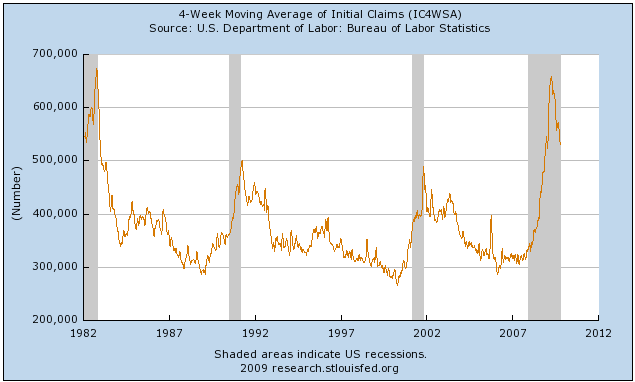

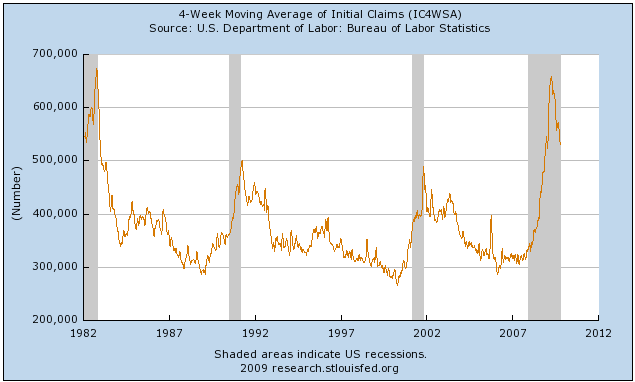

To remind you that the 1991 and 2001 recessions were very shallow compared with 1982 and the present, here is the actual number of claims from 1980-present:

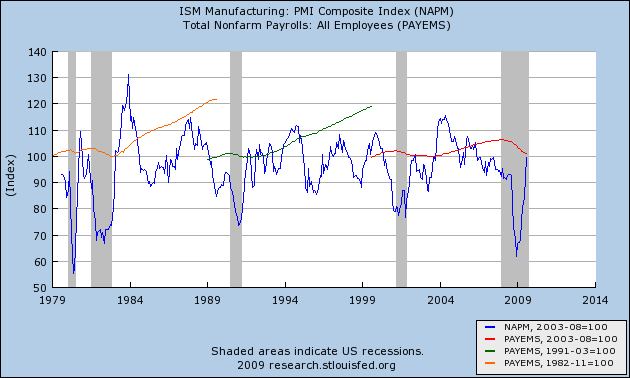

II. ISM Manufacturing

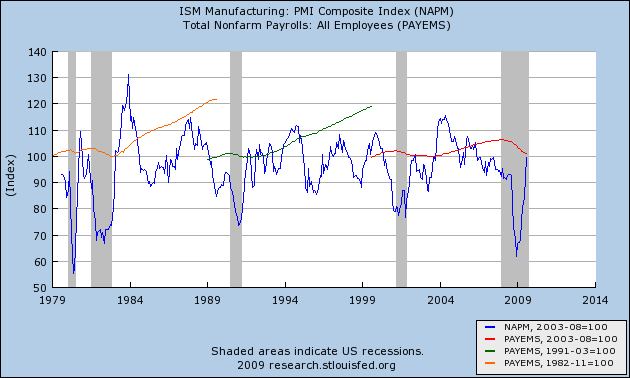

I next looked at the ISM Manufacturing Index, and concluded that the 53 level (50 is the dividing line between expansion and contraction) is the point where jobs began to be added in the very strong recovery after 1982, as well as during the week recoveries of 1992 and 2002. Further, a reading over 54 on the index has always coincided with actual job growth.

Additionally, whenever the hiring vs. firing sub-index is -5 or higher (i.e., no more than 5% more employers plan to fire than hire) and rising, where other evidence indicates a recession is ending, that has always indicated net employment growth was imminent, at least on a temproary basis; and also, whenever current staffing intentions were 65+. and hiring plans were 15+, that has always coincided with positive jobs numbers in the BLS survey, including during and after the "jobless recoveries" of 1992 and 2002.

The ISM manufacturing index stalled out at 52.6 in September, thus the graph looks the same (in the graph, the ISM reading of 53 is normed to 100):

To remind you that the 1991 and 2001 recessions were very shallow compared with 1982 and the present, here is the actual number of claims from 1980-present:

II. ISM Manufacturing

I next looked at the ISM Manufacturing Index, and concluded that the 53 level (50 is the dividing line between expansion and contraction) is the point where jobs began to be added in the very strong recovery after 1982, as well as during the week recoveries of 1992 and 2002. Further, a reading over 54 on the index has always coincided with actual job growth.

Additionally, whenever the hiring vs. firing sub-index is -5 or higher (i.e., no more than 5% more employers plan to fire than hire) and rising, where other evidence indicates a recession is ending, that has always indicated net employment growth was imminent, at least on a temproary basis; and also, whenever current staffing intentions were 65+. and hiring plans were 15+, that has always coincided with positive jobs numbers in the BLS survey, including during and after the "jobless recoveries" of 1992 and 2002.

The ISM manufacturing index stalled out at 52.6 in September, thus the graph looks the same (in the graph, the ISM reading of 53 is normed to 100):

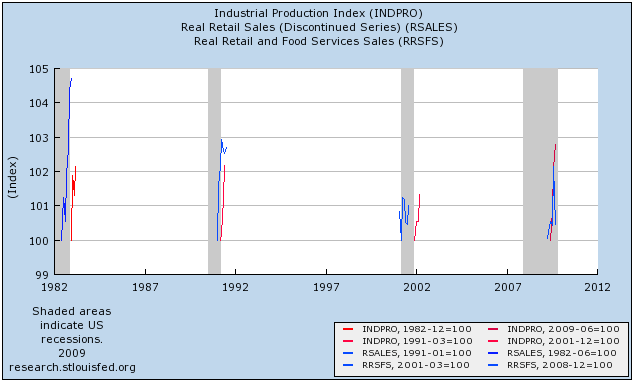

III. Industrial Production

In part 3 of the series I noted that industrial production tends to peak a median +2 months before payrolls, and to trough at the end of recessions a median +1 month before payrolls. Of the 10 troughs since World War 2, in 8 of them industrial production troughed within 2 months of the payrolls number. Further, the only times that industrial production has led employment growth by a relatively long period of time, it has also shown weak growth -- less than 5% a year. In more typical V shaped job recoveries, it has grown at a rate of 10% or more a year.

In September, industrial production continued its strong positive move. I show this graph in conjunction with my discussion of Real retail sales, next.

IV. Real Retail Sales

I described real retail sales as Holy Grail of Leading Indicators for job growth, noting that his consistently turned at both tops and bottoms, an average of 3-5 months before job growth or losses turned. When real retail sales stay flat, they generate a lot of noise, and a longer period between the turn in sales and payrolls. Strong turns in sales generate reliable subsequent moves in payrolls in subsequent months. In general, with regard to recoveries, an increase of about +2.5% a year is necessary to reliably generate a subsequent move in real retail sales.

Because of the unique nature of "cash-for-clunkers", it is difficult to read the last couple of months of this indicator. On a three month smoothed average, it bottomed in April of this year, and on that basis, they are still up only about 0.9% off that low.

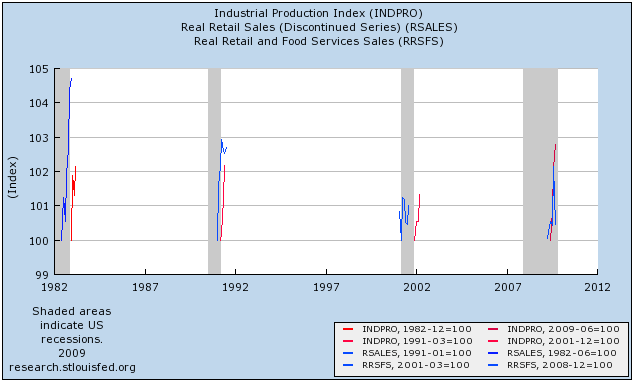

Here is a graph, showing the combined moves of Industrial Production which bottomed 3 months ago(in red), and Real Retail Sales which bottomed 7 months ago (in blue), 3 and 7 months respectively from their lows in the last three recessions as well as currently :

As you can see, because of Industrial production's continued growth in September, it is now up almost 3% -- in excess of the 10% annualized growth correlated with job growth. Industrial production is indeed having a "V" shaped recovery, growing even more than in 1983. By contrast, the expiration of cash-for-clunkers returned Real retail sales to very anemic growth similar to its pattern in the last "jobless recovery," below the 3% annual growth typically associated with job growth. Because of the unique contribution of car sales to this statistic, it is probably more appropriate to average the last two months. Until we see what happens to car sales in October, the jury is out on this number.

V. Summary of the Leading Indicators for Job Growth in the last month

In summary, one indicator (the "holy Grail") Real retail sales, declined, but for unique reasons. One, ISM manufacturing, stalled. But two -- Initial Jobless Claims and Industrial Production -- are now at the levels they simply need to maintain for jobs to be added. Should the Empire State survey be a harbinger, in October ISM manufacturing will join them. Real retail sales, which may improve with renewed car sales, is still the laggard.

VI. How does the poor September Payrolls number fit in?

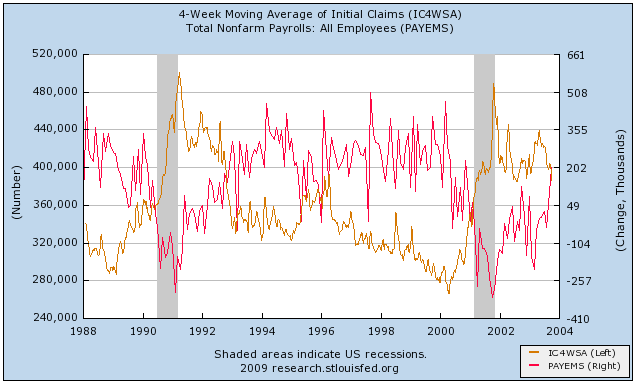

My painstaking analysis immediately got a good kick in the chops by the September jobs number, a more-than-expected decline of -263,000. But there are many paths to the point where a net +1 job is generated. Monthly nonfarm payrolls is a very noisy series compared with the 4 week moving average of initial jobless claims. Here's a graph demonstrating that point, using the two previous recessions and recoveries:

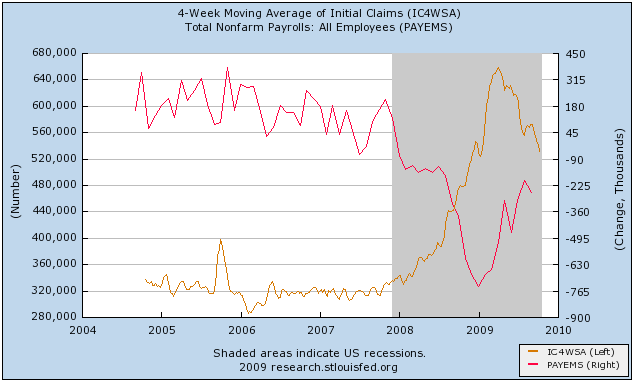

Sooner or later, however, the payrolls data and the jobs data always resolve in the same direction -- which for jobless claims has been continued improvement ever since April:

In other words, the September jobs setback could prove to be (painful) noise hiding an improving signal.

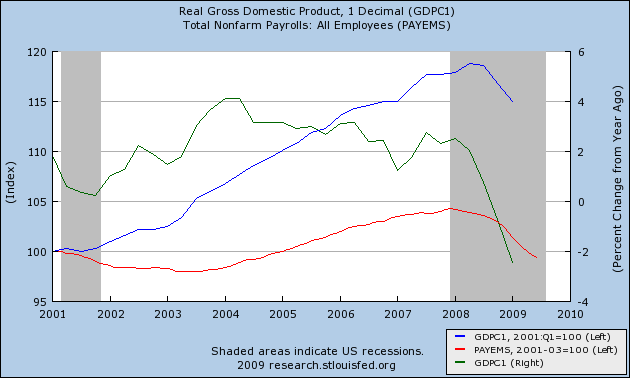

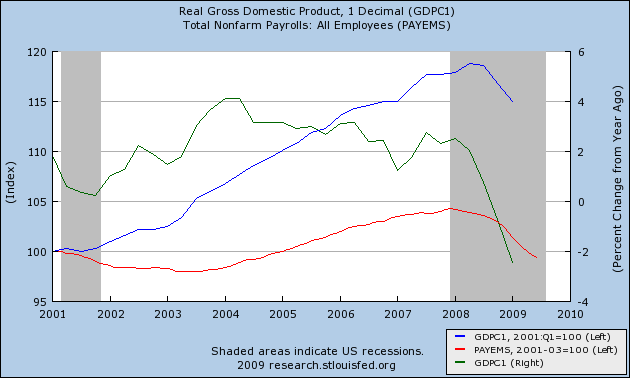

Additionally, I have previously shown in a discussion of "Okun's law" that over the last decade or more it has taken 2% YoY growth in GDP for even 1 net job to be added. Here's the relevant graph demonstrating that relationship (with YoY GDP growth shown in green, payrolls in red):

To reach 2%+ GDP growth by the end of this year, GDP must grow about 4.4% in the 3rd and 4th quarter combined. In that regard, 3Q GDP will be reported next week, and Prof. Krugman has a suspicion that it alone may show a 4% gain, which would put it very close to that +2% YoY figure. Yesterday he was seconded by UCSD Prof. James Hamilton of Econbrowser who said, "That kind of growth is inconsistent with a jobless recovery."

In other words, despite the setback of September payrolls and sideways real retail sales, December may yet be the turning point after which the economy will actually add jobs. Much depends on how real retail sales develop. Again, as I said in my concluding installment last month: let me be the first to acknowledge that this is not a scientific truth or certainty, but a best estimate based on a logical review of existing data with a long history that accommodates both traditional and "jobless" recoveries.

In part 3 of the series I noted that industrial production tends to peak a median +2 months before payrolls, and to trough at the end of recessions a median +1 month before payrolls. Of the 10 troughs since World War 2, in 8 of them industrial production troughed within 2 months of the payrolls number. Further, the only times that industrial production has led employment growth by a relatively long period of time, it has also shown weak growth -- less than 5% a year. In more typical V shaped job recoveries, it has grown at a rate of 10% or more a year.

In September, industrial production continued its strong positive move. I show this graph in conjunction with my discussion of Real retail sales, next.

IV. Real Retail Sales

I described real retail sales as Holy Grail of Leading Indicators for job growth, noting that his consistently turned at both tops and bottoms, an average of 3-5 months before job growth or losses turned. When real retail sales stay flat, they generate a lot of noise, and a longer period between the turn in sales and payrolls. Strong turns in sales generate reliable subsequent moves in payrolls in subsequent months. In general, with regard to recoveries, an increase of about +2.5% a year is necessary to reliably generate a subsequent move in real retail sales.

Because of the unique nature of "cash-for-clunkers", it is difficult to read the last couple of months of this indicator. On a three month smoothed average, it bottomed in April of this year, and on that basis, they are still up only about 0.9% off that low.

Here is a graph, showing the combined moves of Industrial Production which bottomed 3 months ago(in red), and Real Retail Sales which bottomed 7 months ago (in blue), 3 and 7 months respectively from their lows in the last three recessions as well as currently :

As you can see, because of Industrial production's continued growth in September, it is now up almost 3% -- in excess of the 10% annualized growth correlated with job growth. Industrial production is indeed having a "V" shaped recovery, growing even more than in 1983. By contrast, the expiration of cash-for-clunkers returned Real retail sales to very anemic growth similar to its pattern in the last "jobless recovery," below the 3% annual growth typically associated with job growth. Because of the unique contribution of car sales to this statistic, it is probably more appropriate to average the last two months. Until we see what happens to car sales in October, the jury is out on this number.

V. Summary of the Leading Indicators for Job Growth in the last month

In summary, one indicator (the "holy Grail") Real retail sales, declined, but for unique reasons. One, ISM manufacturing, stalled. But two -- Initial Jobless Claims and Industrial Production -- are now at the levels they simply need to maintain for jobs to be added. Should the Empire State survey be a harbinger, in October ISM manufacturing will join them. Real retail sales, which may improve with renewed car sales, is still the laggard.

VI. How does the poor September Payrolls number fit in?

My painstaking analysis immediately got a good kick in the chops by the September jobs number, a more-than-expected decline of -263,000. But there are many paths to the point where a net +1 job is generated. Monthly nonfarm payrolls is a very noisy series compared with the 4 week moving average of initial jobless claims. Here's a graph demonstrating that point, using the two previous recessions and recoveries:

Sooner or later, however, the payrolls data and the jobs data always resolve in the same direction -- which for jobless claims has been continued improvement ever since April:

In other words, the September jobs setback could prove to be (painful) noise hiding an improving signal.

Additionally, I have previously shown in a discussion of "Okun's law" that over the last decade or more it has taken 2% YoY growth in GDP for even 1 net job to be added. Here's the relevant graph demonstrating that relationship (with YoY GDP growth shown in green, payrolls in red):

To reach 2%+ GDP growth by the end of this year, GDP must grow about 4.4% in the 3rd and 4th quarter combined. In that regard, 3Q GDP will be reported next week, and Prof. Krugman has a suspicion that it alone may show a 4% gain, which would put it very close to that +2% YoY figure. Yesterday he was seconded by UCSD Prof. James Hamilton of Econbrowser who said, "That kind of growth is inconsistent with a jobless recovery."

In other words, despite the setback of September payrolls and sideways real retail sales, December may yet be the turning point after which the economy will actually add jobs. Much depends on how real retail sales develop. Again, as I said in my concluding installment last month: let me be the first to acknowledge that this is not a scientific truth or certainty, but a best estimate based on a logical review of existing data with a long history that accommodates both traditional and "jobless" recoveries.