- by New Deal democrat

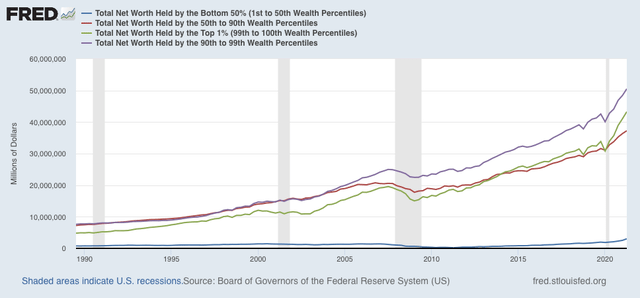

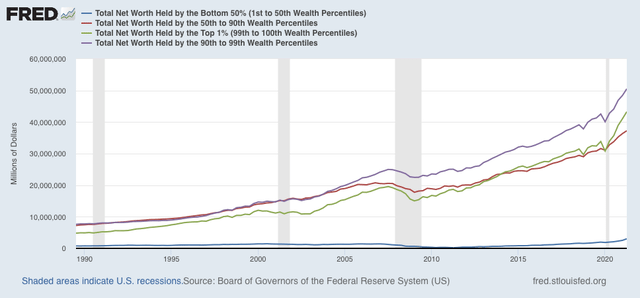

The desert of new economic data this week continues today. But last week the Fed released its quarterly data on wealth distribution in the US, and it shows an important point about the efficacy of the emergency pandemic assistance. Let’s take a look.

Let’s start with the raw absolute levels of total wealth held by the bottom 50%, 50%-90%, 90-99%, and top 1% of the US population:

The total net worth of the US as of Q2 of this year was about $134 trillion (yes, trillion). Of that, only $3 trillion was held by the entire bottom half of the population. At the other extreme, the top 1% alone held assets worth $43 trillion.

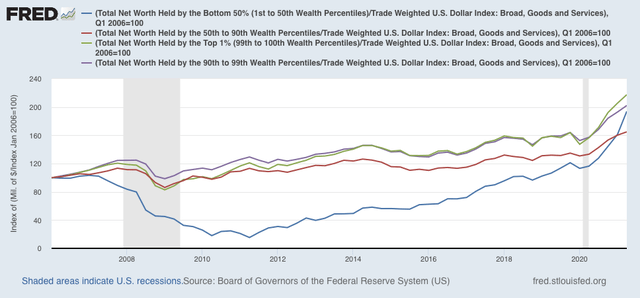

Since the bottom half of the distribution shows up as squiggles at the bottom of the graph above, to better show the fluctuations among the groups, here is the same information normed to 100 as of the beginning of the series in 1989:

Most noteworthy is the virtual collapse - by nearly 90%! - in assets held by the bottom 1/2 of the population between its temporary peak in 2000 and several years after the end of the Great Recession in 2011. By contrast, with the exception of the stock market pullbacks during the tech crash and the first part of the Great Recession, the value of assets held by the top 1% has almost relentlessly increased in the past 30+ years.

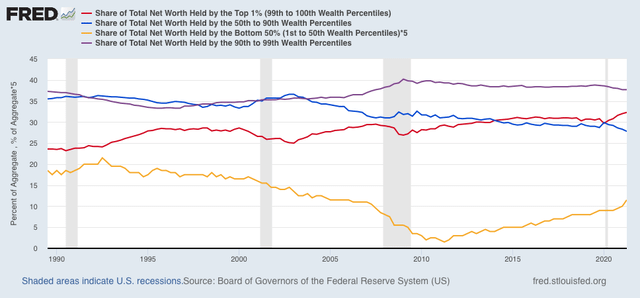

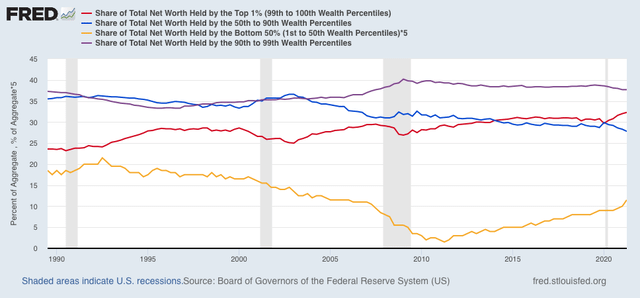

Another way of looking at this is the %age share of total net US assets held by each wealth percentile, shown below:

Again, with the brief exception of stock market pullbacks, the share of US assets held by the top 1% (red line) has increased almost continuously since 1989. By contrast, the share held by the bottom 50% (gold, multiplied *5 so that it shows up as more than squiggles) declined by 93% from 4.3% in 1992 to 0.3% in 2011. A secondary phenomenon in both the absolute and %age share numbers is that the 50th-90th%iles (blue) and the 90th-99th%iles (purple) held roughly steady with one another until the 2000s, after which the wealthier cohort pulled away from the middle class cohort, and has retained that advantage since.

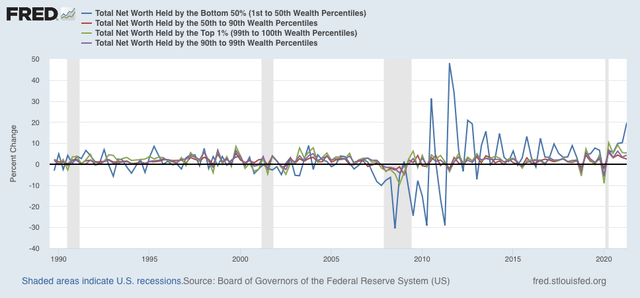

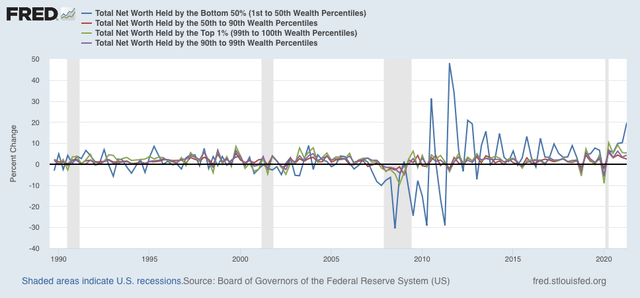

Next, let’s look at the YoY% change in wealth for each group:

What is most noteworthy here, aside from the pasting that the poorer half of the US wealth distribution took during and after the Great Recession (frankly, a real indictment of both Bush’s and Obama’s emergency packages that bailed out Wall Street and the banks and left Main Street dangling), is the ground made up by the bottom half of the wealth distribution in the latter part of the last expansion and even more dramatically as a result of the emergency measures put in place to deal with the pandemic. In absolute terms, the bottom 50% holds more wealth than at any point in the series (note, of course, this is not adjusted for inflation), but also the highest share of total assets than at any point since early 2006 - but still, only slightly more than 1/2 as much as the share they held at the end of the 1980s.

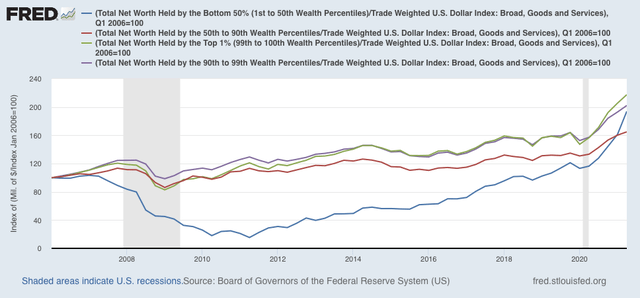

Finally, to give some indication of how this plays out in “real” terms, here are the total wealth amounts normed to 100 in 2006, and adjusted for the trade weighted value of the US$:

Again, how badly the poorer half of the US was treated during the Great Recession and the first part of the recovery thereafter shows up strongly, as does how well they did relatively speaking in the latter part of the expansion, and even moreso with the emergency pandemic assistance.