- by New Deal democrat

If you’ve paid much attention to the financial press in recent days, you have probably read stories that the yield curve - the line that traces the difference in rates in different length bond maturities - has moved towards un-inverting. That is, the situation whereby short term rates are higher than long term rates is moving in the direction of reversing towards a more usual pattern of longer term rates being higher.

But you’ve probably also heard this referred to as a “bearish steepening.” That means that the un-inversion of the yield curve isn’t happening because short term rates are moving lower, but rather because long term rates have been headed higher.

Is a “bearish steepening” of the yield curve in fact bad? Yes, it is. That’s because it means that the interest rates that consumers and businesses have to pay on loans are also headed higher. Those loans become more expensive, and economic activity slows down.

So let’s go to the graphs.

First, here is a graph for the past 2 years of the Fed funds rate (red) compared with 10 year Treasury rates (blue):

When the red line moved above the blue line, that was an inversion. The inversion still exists, but the two lines reached their maximum difference in early May. Since then, and especially in the past month, the two lines have moved closer, mainly because Treasury rates have headed higher. That’s the “bearish steepening.”

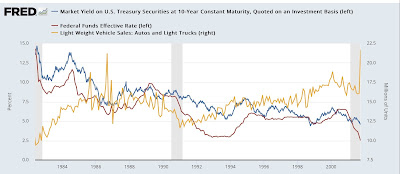

Has this happened before? Here’s a look at the same data over last 40 years:

Note that several times in the 1980s and 1990s (particularly 1984 and 1994) both the Fed funds rate and Treasury rates moved higher. There was also one instance where an inversion resolved to higher rates (1998).

Let’s take a close look at these. Below I again show 10 year Treasury rates (red, right scale) compared with the yield curve measured by the difference between 10 year and 3 month Treasury maturities (blue, left scale):

We can see at least 5 instances in the 1980s and 1990s when the yield curve became more positive (i.e., longer rates relatively higher than shorter rates) at the same time as long rates themselves moved higher: 1984, 1986, 1994, 1996, and 1998. As mentioned above, only in the last case had the yield curve inverted.

The good news is, in no case following these “bearish steepenings” did a recession happen in the next 12 months. But the bad news, in all but one of these cases for our purposes, is why.

Focus on the red line (Treasury interest rates). In 3 of the 5 cases - 1984, 1994, and 1996 - long term interest rates moved back down within 12 months to rates close to or even below the level they had been before the steepening began. This allowed consumers either to refinance mortgage debt at lower rates, or to buy new houses or vehicles at lower rates of financing.

To wit, here’s what happened with housing permits in the 1980s and 1990s (gold, right scale) compared with both long term rates and Fed funds rates:

In 1985, 1995, and 1997, housing permits increased significantly as buyers were able to lock in lower interest rate mortgages.

Although the data is noisier, the same thing happened with light vehicle sales:

Note there is a longer delay before vehicle sales moved higher or lower. This is because of a delay in the changes in motor vehicle financing rates:

But what about the other two times? In both 1986 and 1998, the economy was bailed out by 25% declines in gas prices (not shown). Even so, because interest rates did not decline to new lows in 1999, housing permits (see above) continued to decline, helping set the stage for the ultimate 2001 recession.

So what about now? Remember that housing permits follow interest rates with a 3-6 month lag. Permits recently improved, following the decline in interest rates earlier this year. That is very likely to reverse lower in the months ahead (possibly beginning with tomorrow’s report for September):

And motor vehicle sales are giving equivocal signals, suggesting that they may be peaking:

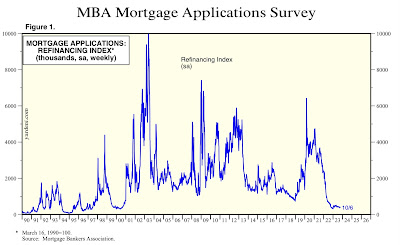

Finally, turning to refinancing itself, here is a long term graph from

Edward Yardeni of the Mortgage Bankers Association’s Refinancing Index:

Although the graph does not show the 1980s, note that refinancing all but stopped in 1994, but resumed with a sharp increase in 1995, and again in 1996-97. But it declined sharply and stayed down for a year or more in 1999-2000. The inability of consumers to refinance at lower mortgage rates, thus freeing up money for other spending, was a significant precursor to the 2001 recession.

As shown in the second graph from the top above, long term rates failed to make new lows for at least 3 years before the onset of the 1991, 2001, and 2008 recessions. As a result, as time went on, refinancing declined sharply. There were renewed bouts of refinancing after the Great Recession, and after the pandemic lockdowns, as long term rates hit new lows again. It is quite unlikely that we will see long term interest rates as low as they were in 2020 during our lifetimes, and 3 years have passed since then:

Now interest rates are at 10+ year highs, and as you can see from Yardeni’s graph, refinancing is all but dead. Even when interest rates go down again, because they are *very* unlikely to go as low as they were in 2020, refinancing is unlikely to be anywhere even remotely as common as it was between 2001-2020.

In conclusion, unless the yield curve actually un-inverts, the recession signal from its inversion remains. And the increase in long term interest rates can be expected to put further pressure on both business and consumer borrowing. It is indeed a “bearish steepening.”