- by New Deal democrat

Here are the bottom line paragraphs from my 2015 forecast one year ago:

This [the Index of Leading Indicators] is pretty straightforwardly showing good growth in the first part of 2015. Prof. Moore's list of Short Leading Indicators (some of which are the same as the Conference Board's, and which also look forward about 4 to 8 months out, signals the same.....

... [I]n 2014, a deceleration in housing's contribution to GDP was offset by an increase in governments' contributions at all levels. Neither Federal nor state and local spending has returned to their pre-recession rates of growth, and at the state and local levels, it is likely there will be further improvement. Possibly Washington can manage to avoid more own-goals. If so, those are pluses for growth in 2015, which should continue to offset the impact on the broader economy of the housing slowdown of 2014.

In summary, when looking at the long leading indicators, all of them are moving in the right direction. [With a few caveats,] .... it is a safe bet that growth - including jobs and wages - will continue throughout 2015. Depending on what happens with governments' contributions (as set forth just above), my expectation is for YoY growth in 2015 to be approximately equal to its 2014 levels. If gas prices remain low, and housing picks up soon enough due to lower interest rates, then this may be the best year of the expansion yet.

I am scoring this as one hit and one miss.

We did manage to escape any negative quarters of GDP:

So far the Atlanta Fed's "GDPNow" estimator is calling for weak but positive growth in Q4 as well.

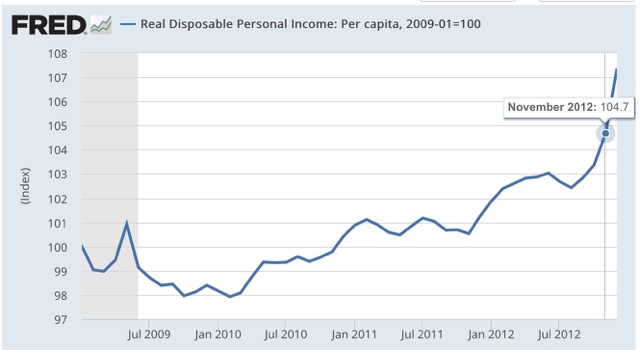

So I was correct to forecast continued growth this year in both the 6 and 12 month frames. And jobs and real wages did continue to grow YoY as well:

That's the hit.

But the YoY% change in GDP has declined this year compared with 2014:

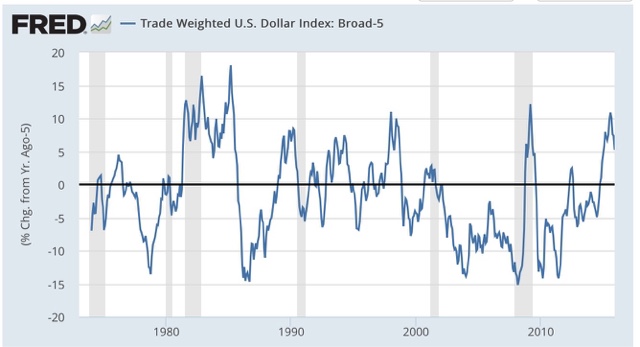

Even though housing did pick up as I forecast, and even though government expenditures stopped being a drag, the super-strong US$ clobbered the globally exposed portion of the economy, and just about all of my mid-cycle indicators have peaked and started to decline. That's the miss.

I always try to learn from my misses, and in this case that has caused me to integrate the US$ into my system as a short leading indicator.

In the next couple of weeks, I will issue my fearless forecast for 2016. In the meantime, Happy New Year!