- by New Deal democrat

- Whether there is further deceleration in jobs gains compared with the last 6 month average

- Whether the unemployment rate is neutral or decreasing; or whether there is further weakness; and

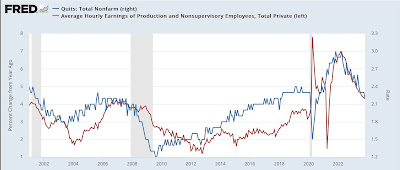

- Based on the leading relationship of the quits rate to average hourly earnings, weather YoY wage growth continues to decline slightly

The news on all three was good. The six month average of jobs gained has steadied, at 198,500 an increase from last month. The unemployment rate remained steady at 3.7%. Average hourly wages for nonsupervisory workers also remained steady at 4.3%.

There is an important caveat about this month’s numbers: data from the household report’s seasonal adjustments was changed. This means that m/m changes in those metrics (which were otherwise very bad) need to be taken with a hefty dose of salt.

Here’s my in depth synopsis.

- 216,000 jobs added. On a YoY basis, jobs rounded to up 1.7%, down -0.1% from last month, and the lowest % gain since March 2021

- Both October and November were revised downward, by -45,000 and -26,000 respectively, for a total of -71,000. This continued the steady drumbeat of downward revisions that we saw almost all last year. The 3 month moving average declined from 180,000 to a new post-pandmic low of 165,000.

- Private sector jobs increased 164,000. Government jobs increased by 52,000.

- The alternate, and more volatile measure in the household report, declined by -683,000. November, which was originally reported as a big rebound of 747,000, was also revised downward to 586,000. More importantly, the YoY% gain in this report - which avoids issues with seasonal adjustment - declined to +1.2%, the lowest since the pandemic lockdowns.

- The U3 unemployment rate remained at 3.7%. The civilian labor force, the denominator in the figure, declned by -676,000, while the numerator, the number of unemployed, rose a tiny 6,000.

- The U6 underemployment rate increased +0.1% to 7.1%, 0.6% above its low of December 2022.

- Further out on the spectrum, those who are not in the labor force but want a job now increased 328,000 to 5.671 million, vs. its post-pandemic low of 4.925 million set last March.

- the average manufacturing workweek, one of the 10 components of the Index of Leading Indicators, declined another -0.1 hours to 40.4, equal to its lows earlier this year and down -1.1 hours from its February 2022 peak of 41.5 hours.

- Manufacturing jobs rose 6,000.

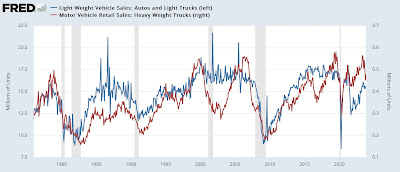

- Within that sector, motor vehicle manufacturing jobs declined 2,100.

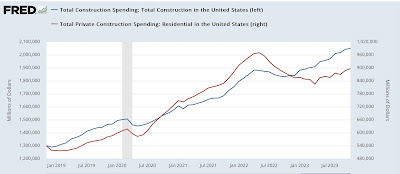

- Construction jobs increased by 17,000.

- Residential construction jobs, which are even more leading, rose by 3,900. This is a new post-pandemic high.

- Goods jobs as a whole rose 22,000 to a new expansion high. These should decline before any recession occurs. They remain up 1.0% YoY, which is an average pace compared with most of the last 40 years, although the trend continues to be slight deceleration.

- Temporary jobs, which have generally been declining late 2022, declined again, by -33,300, and are down about -250,000 since their peak in March 2022.

- the number of people unemployed for 5 weeks or fewer rose 122,000 to 2,191,000.

- Average Hourly Earnings for Production and Nonsupervisory Personnel increased $.10, or +0.3%, to $29.42, a YoY gain of +4.3%. This is unchanged from one month ago, but remains the lowest since June 2021.

- the index of aggregate hours worked for non-managerial workers fell -0.1%, but is up 1.4% YoY, an improvement from October’s low of 1.0%.

- the index of aggregate payrolls for non-managerial workers rose 0.2%, and is up 5.8% YoY. This is 0.3% above the YoY low set in October, and 2.7% above the most recent inflation rate, meaning average working class families have more buying power.

- Leisure and hospitality jobs, which were the most hard-hit during the pandemic, rose another 40,000, which is still -163,000, or -0.9% below their pre-pandemic peak.

- Within the leisure and hospitality sector, food and drink establishments rose 22,100,. This sector has completely recovered from its pandemic downturn.

- Professional and business employment increased 13,000. These tend to be well-paying jobs, This series has declined by -71,000 since last May, and is currently up only 0.6% YoY. This appears to be mainly fueled by retrenchment in tech jobs.

- The employment population ratio declined -0.3% to 60.1%, vs. 61.1% in February 2020.

- The Labor Force Participation Rate also declined -0.3% to 62.5%, vs. 63.4% in February 2020.