Hey all. This is Bonddad. I haven't been around here in ... a really long time. As in, there was another president the last time I posted here. Since my last posting and this one, I've been a few places. NDD and I were over at XE.com for a long time. Then I migrated over to Seeking Alpha -- where I still write about the economy and economics (more on that below) -- largely because they have an exclusive author program that pays people. And, I like money.

But ... I'm back here now -- at least for this column.

So, what is the "Passive/Aggressive" investor? Simple: it's for people who take a hands-on (aggressive) approach to passive/index style investing. Instead of buying a stock or a company, you buy a group of ETFs, balance them a way that you like, and leave it there until something fundamental changes to make you reallocate your portfolio.

For example, suppose we're at the beginning of an expansion. The markets are cheap; after rallying at the end of the last expansion, bonds are probably selling off a bit. Certain sectors (basic materials, industrials) start to look attractive because they'll start to see their profits increase with the coming economic expansion. So, you put together a portfolio of small cap indexes (like the IWC, IWM), a few sector ETFs (like the XLB and XLI), and a broad-based emerging market ETF (like the VWO), balance it a certain way, and leave it there.

Throughout the expansion you reallocate based on economic fundamentals. For example, about 9-12 months into the expansion, news from Asia starts to pick-up. ISMs are rising, GDP is growing, trade in increasing and unemployment is declining. To take advantage of this trend, you add an ETF with broad exposure to Asia. At the same time, you think the rally in basic materials has run its course but you think consumer spending will pick-up. So, you sell your position in XLB and buy the XLY.

About 9-12 months later, you think the rally is entering mid-life, so you want to move from small caps (like the IWC or IWM that your purchased at the beginning of the rally) to a larger cap index like the QQQ or SPY. You also think that things are really heating up in Europe, so you add an ETF that broadly tracks that geography.

Then, when you think the rally is getting a little long in the tooth, you sell the QQQ and move to the SPY or OEF, trading up for even larger caps. You also sell your emerging markets and Asia exposure and buy some longer-dated bonds (which typically rally towards the end of an expansion). You also think the consumer is getting ready to slow his spending, so you sell the XLY and buy utilities and health care (the XLU and XLV), thinking that a more defensive position is what's needed.

There are a few concepts/ideas at the core of this investment style. First, it's slower moving. Instead of day-trading or looking for shorter-term trades, the style is based on holding periods of at least six months and probably longer. Second, it's intimately tied to the underlying economic data and being aware of it, because, (third) you're trading on broad investment themes rather than company-specific information.

So, what will I be covering on a regular basis? First, I'll be looking at the performance of the following broad-based equity ETFs.

Above are a number of US based ETFs that run the gamut from small (IWC and IWM) to mid (IJH) to large (QQQ, SPY) cap US stocks. I've also got ETFs that track Asia, Latin America, Europe, developing, and developed markets. Finally, I've got three dividend focused ETFs to add an equity income component.

Next up are the bond market ETFs:

Like the equity ETFs, I've chosen a broad-swath of sectors that run the gamut from the US to international, from short-term corporate to junk.

And finally, I'll by looking at the "dividend aristocrats" -- stocks that have consecutively increased their dividends for the last 25 years. However, I look at these companies a bit differently. Aristocrats are large companies with a very long track record. In some cases, they've been around for over a century. They're usually major international players with very sophisticated management. They're not going to grow that fast, if at all. And practically every major money manager has to buy them in some proportion. Due to all these factors, when they hit 52-week lows (or are trading near the bottom of their respective ranges) you should consider buying them. At that point, I think of these stocks like bonds trading below par. I look for a strong balance sheets and cash flow to make sure the dividend payments will keep coming. For example, right now, Exxon (XOM) is trading near a 52-week low with a yield slightly over 5% -- which looks really attractive when compared to the 10-year treasury's yield of 1.51%. That doesn't mean I think it's a good buy; the energy sector has performed poorly over the last few years and the current outlook is questionable. But since Exxon's trading near a 52-week low with a great yield, you could also argue that it can't get much lower.

In addition, to looking at these four investment areas, I'll also be looking at various portfolio construction ideas and concepts to give you ideas for how to put one together for yourself. And, once, I have a basic format down I may (repeat MAY) add in a general legal section that covers high-level issues like the retirement plan mechanics, basic estate ideas concepts, and other nuts-and-bolts financial things people would need information on.

Finally, you should read this column in conjunction with my work at Seeking Alpha, because they're part of a unified set.

Most trading days I write Technically Speaking, which looks at general economic trends and day along with the US markets. This will give you regular updates on the overall market direction.

On Friday's I write a longer Technically Speaking, which covers major international numbers and a brief economic overview of major geographic regions, a summer of major central bank activity, a US economic data summary and analysis, along with a look at the charts of the US markets.

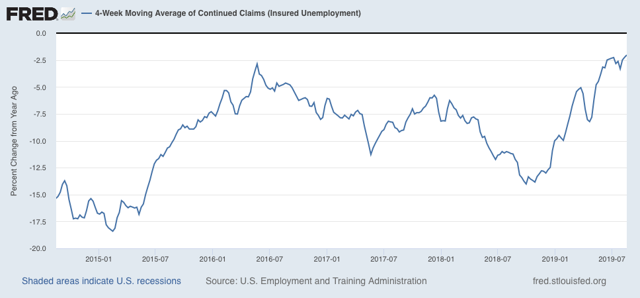

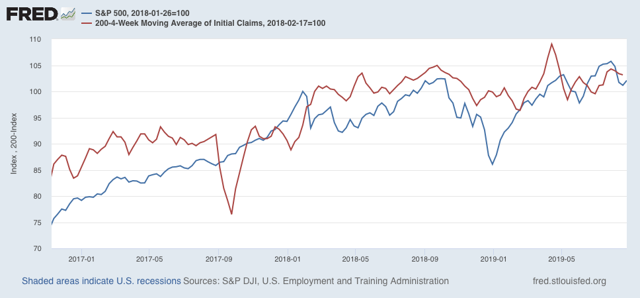

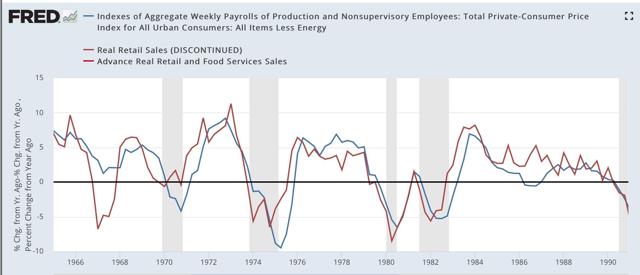

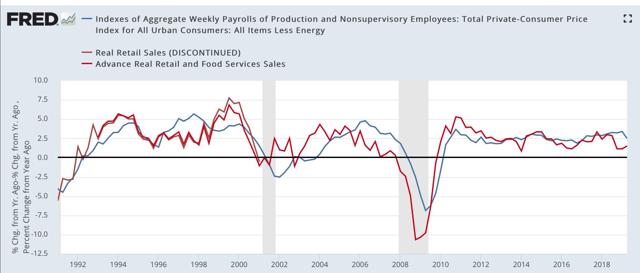

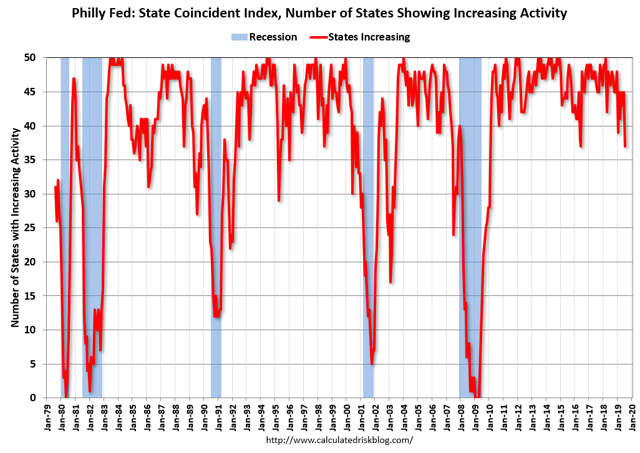

Most weekends, I write Turning Points, which uses the Arthur Burns, Geoffrey Moore system of long-leading, leading, and coincidental data to see how close or far the US is to a recession.

I've just started a once-a-month overview of geographic regions (starting with Asia) where I look at leading and coincidental data of major economies in each region.

In fact, all of those articles naturally feed into this column.

Any, it's good to be back.