- by New Deal democrat

December consumer prices indicate that we are leaving the immediate post-covid era and seeing a rebalancing of sectors, as sectors that declined sharply in the past several years rebound.

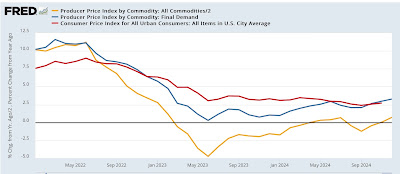

As in November, the only two categories of “hot” numbers showing price increases of 4.0% a year or more are two laggards: shelter and transportation services. All of the former problem children are now more or less in line.

As per usual, the biggest dichotomy in the numbers is shelter vs. ex-shelter, but let’s start with the headline and core CPI readings. For the record the former increased 0.4% for the month, while the latter increased only 0.2%. On a YoY basis, headline prices are up 2.9%, an increase of 0.5% from their 2.4% low three months ago. Core prices excluding food and energy are up 3.2% YoY:

Now let’s look at CPI for shelter vs. ex-shelter:

Shelter prices increased 0.3% for the month. Everything else all together rose a sharp 0.5%. On a YoY basis, shelter increased a little under 4.6%, its lowest such reading since January 2022. Despite the “hot” monthly reading, all other prices increased 1.9% YoY, the 20th month in a row they have risen less than 2.5%.

As it has been for several years, in the broadest terms inflation in excess of the Fed target remains almost all about shelter.

Within shelter, both actual rents and “owners equivalent rent,” the fictitious measure of house prices, increased 0.3%. On a YoY basis, rent increased 4.3% while OER increased 4.8%. Both of these are the lowest since early 2022:

While the deceleration in shelter inflation has been slow, it is continuing as forecast from both the leading house price and new apartment rent indexes. To reiterate what I wrote last month, the Philadelphia Fed’s experimental new and all rent indexes, which are designed to lead the CPI for rents, for the last two quarters have forecast a decline below 4% YoY, and at the current pace of deceleration, that forecast could come to fruition within the next 2 to 3 months.

Turning to the other remaining problem child, transportation services (mainly insurance and repair costs); recall that these lag vehicle prices. In December, new vehicle prices increased 0.5%, and used car prices increased 1.2%. These have been strong monthly numbers in th past few months. But on a YoY basis, new car prices are down -0.4%, and used car prices down -3.3%. In other words, this is a rebound from the pullback since 2023 [Note: instead of YoY, graph is normed to 100 as of just before the pandemic, better to show the surge in prices and the stagnation or decline afterward]:

In December transportation services costs increased 0.5%. On a YoY basis, they rose from 7.1% to 7.3%, which is still nearly the “best” reading in 3 years:

Within transportation services, motor vehicle repairs are up 6.2% while insurance is up 11.3%.This is the real problem child is motor (for which unfortunately FRED does not provide a graph).

What the above all means is that if we were to take out the two areas that we know lag, shelter and transportation services, consumer inflation would probably be up only something like 1% YoY.

Another former problem child of food away from home increased 0.3% this month, and is up 3.6% YoY, the lowest increase in over 4 years:

Last month I wrote that another emerging sector of concern is medical care services. This month they increased 0.2%, while the YoY measure decelerated to 3.4%, which is good news, as in the context of the past 10 years, this increase is only a little above average:

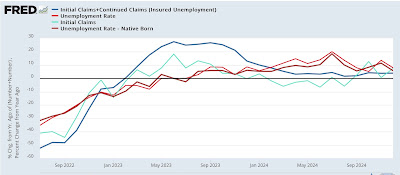

Before I finish, let me also update one important labor sector graph.

Nominally aggregate payrolls increased 0.4% in December, which means that after adjusting for today’s inflation number, real aggregate payrolls were unchanged, but at their record high:

This is consistent with continued economic expansion over the near term.

So let’s conclude. The lagging sectors - shelter, and motor vehicle repairs and insurance - are the primary sources of remaining high inflation. But both are decelerating as expected. At these same time, new and used car prices are rebounding from their stagnation (new cars) and deep declines (used cars) of the past several years, as are energy prices. Because the former are decelerating more slowly than the latter are rebounding, headline inflation has started to increase again.