A glut of foreclosed homes of historic proportions is starting to drive down U.S. home prices faster as lenders put more properties on the market and buyers show signs of interest.

The ability of America's lenders to manage this fire sale will be crucial to determining how long the housing market stays in the dumps -- and how quickly blighted neighborhoods can heal. The oversupply is severe: In some major markets, including Las Vegas and San Diego, foreclosure-related sales have accounted for more than 40% of all sales in recent months.

On Monday, new data suggested that pressures like these are starting to drive prices low enough to attract some buyers back into the market. Sales of previously occupied homes jumped 2.9% in February from the month before, the National Association of Realtors said, the first increase since July.

The median price dropped 8.2% from a year earlier to $195,900, the biggest drop recorded by the Realtors in the current slump.

In some beaten-down markets, the price cuts have been stark. The Detroit Board of Realtors recently found that home sales in the city (excluding suburbs) in the first two months of this year jumped 48% from a year earlier, to 1,540. The average home price there sank 54% to about $22,000.

'Got to Move Things'

Banks and others holding foreclosed property have concluded "we've got to move things" and are finally willing to slash prices, says Thomas Lawler, a housing economist in Leesburg, Va.

The supply is piling up fast. Overall, the total number of lender-owned homes doubled last year but sales grew only 4.4%.

This is the first set of positive data we've seen. Don't expect this to be a rapidly improving situation. For the following reasons.

First, note the amount of raw inventory (graphs from Calculated Risk):

This translates into a huge months of supply:

Vacancy rates are at their highest levels since 1960.

This vacancy rate is already causing huge problems. From Reuters:

Like many cities in the United States where the home vacancy rate has scaled its highest since records began in 1956, the former textile mill city of Worcester in Massachusetts is turning to the courts to fight back.

Their target: banks who abandon properties and who leave behind a glut of empty, dilapidated houses that draw crime, cut tax revenue and depress nearby property values in a market already in a tailspin.

......

The city of 175,898 people, a munitions depot during the U.S. Revolutionary War, offers a window into how U.S. cities are grappling with a wave of foreclosures that has pushed the U.S. homeowner vacancy rate to a record 2.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2007 -- or about 1 million homes.

Like many U.S. mayors and city officials, O'Brien blames "predatory" lending practices prevalent in the U.S. property boom for the lion's share of about 4,220 mortgages in his city that are either in, or at risk of, foreclosure.

.....

In western New York, the city of Buffalo filed a lawsuit on February 21 against 36 lenders -- including big names like JPMorgan Chase & Co Inc and Countrywide Financial Corp -- who were involved in 57 foreclosures that led to properties being abandoned and ultimately demolished by authorities.

The struggling Rust Belt city, plagued by about 10,000 vacant homes and commercial buildings, estimated the 57 foreclosures cost Buffalo $1 million in demolition work and another $1 million in nuisance costs -- from police patrols to boarding up buildings, to the social toll on communities.

.....

Further east, Syracuse, New York, began selling vacant homes last year for $1 each to non-profit groups who promise to tear them down or renovate them. Last month, Syracuse Mayor Matthew Driscoll extended the deal to private companies.

In other words, the raw amount of supply out there is huge.

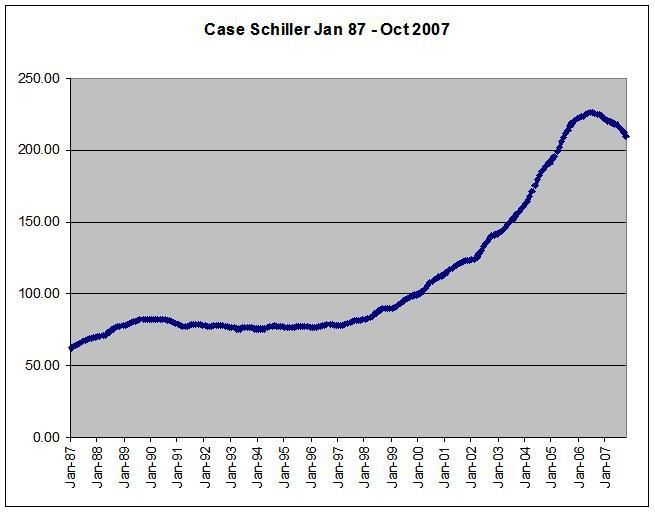

Prices still have a long way to go before we're at the end of price drops.

There's an old economic maxim: prices have a way of reverting to the mean (or sometime like that). It simply means there is a historical/average/median price that we can find from simple math. Notice on the above chart we're way outside of that norm.

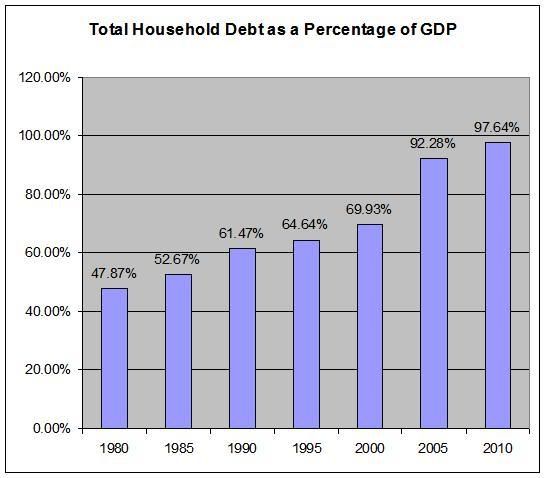

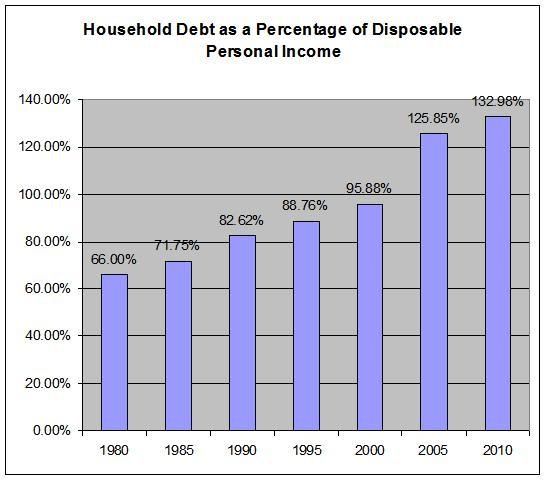

Finally -- who is going to buy these houses? The US consumer is already in debt up to his eyeballs:

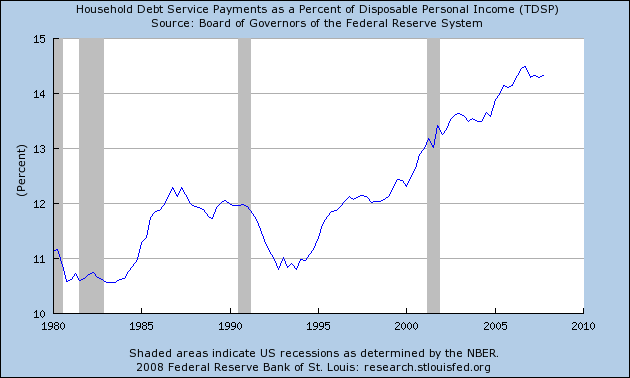

Debt service payments are at all time highs

Household equity is at all time lows.

And high commodity prices are taking their toll as well:

By the end of 2007, 36 percent of consumers' disposable income went to food, energy and medical care, a bigger chunk of income than at any time since records were first kept in 1960, according to Merrill Lynch.

And this is before any discussion about who is going to lend the money to consumers? The financial sector is still reeling from tons of writedowns. And this is before we consider information from the latest Quarterly Banking Survey: