The Federal Reserve has its own language. As a tax lawyer, I am well aware of bizarre language (ever try and work with the tax code?) The Fed is the same way. They have their own way of talking.

There have been a few recent fed speeches that seem to indicate the Fed is deeply concerned about the markets and will most likely lower interest rates at their next meeting.

Let's start with San Francisco Federal Reserve President Janet Yellen:

With these developments in mind, let me review the economic situation. By the time of the October meeting, the data indicated that the economy had turned in a very strong performance in the second and third quarters. However, the fourth quarter is sizing up to show only very meager growth. The current weakness probably reflects some payback for the strength earlier this year—in other words, just some quarter-to-quarter volatility due to business inventories and exports. But it may also reflect some impact of the financial turmoil on economic activity. If so, a more prolonged period of sluggishness in demand seems more likely. The timing of the slowdown certainly matches well with the financial turmoil explanation. Of course, much of the data that drove the third quarter strength cover the earlier part of that quarter, just the very beginnings of the turmoil in July and August, and therefore probably do not reflect its effects very much. However, the data for the end of the quarter—that is, for September—did come in on the soft side, and the data for the beginning of the fourth quarter in October have shown even more of a slowdown.

While correlation does not usually mean causation -- that is, just because things happen at the same time does not mean one causes the other -- her statement that, "The timing of the slowdown certainly matches well with the financial turmoil explanation." makes a great deal of sense. Credit is the life blood of the economy; when its harder to get, everybody suffers.

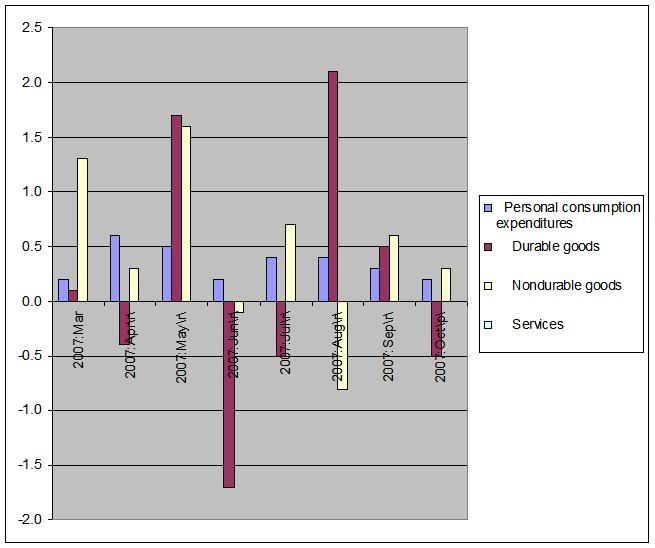

In addition, recent numbers have not been good. Personal consumption expenditures were weak, as were durable goods. Oil is a drag. Retail sales are fair but not great. In short, the numbers could be a lot better.

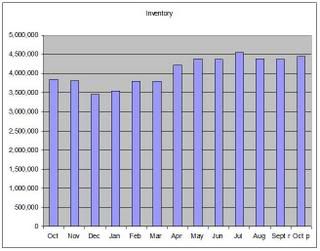

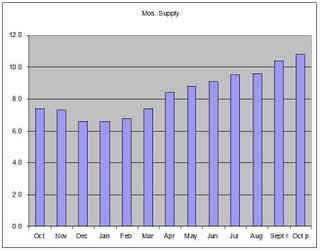

I’d like to go into this “story” in more detail. First, the on-going strains in mortgage finance markets seem to have intensified an already steep downturn in housing. Indeed, forward-looking indicators of conditions in housing markets are pointing lower. Housing permits and sales are dropping, and inventories of unsold homes are at very high levels. Moreover, rising foreclosures will likely add to the supply of houses on the market. It’s well known that foreclosures on subprime adjustable rate mortgages have increased sharply over the past couple of years. More recently, we’ve begun to see increases in foreclosures on subprime fixed-rate mortgages and even on prime ARMs. The bottom line is that housing construction will likely be quite weak well into next year before beginning to turn around.

Turning to house prices, many measures at the national level have fallen moderately, and the declines appear to be intensifying. Indeed, the ratio of house prices to rents, which is a kind of price-dividend ratio for housing, remains quite high by historical standards, suggesting that further price declines may be needed to bring housing markets into balance. This perspective is reinforced by futures markets for house prices, which indicate further—and even larger—declines in a number of metropolitan areas this year.

Here Yellen gives a great overview of the basic problems of the housing market. Excess supply = lower prices. Rising foreclosures = more supply for an already bloated market = lower prices.

In addition, with the credit market turmoil listed above, it's harder for people to get loans to buy houses. That means demand is drying up.

In shorter version, here is a chart of the total existing homes available for sale:

And here is a chart of months of inventory available for sale at the current sales pace:

This weakness in house construction and prices is one of the factors that has led me to include a “rough patch” in my forecast for some time. More recently, however, the prospects for housing have actually worsened somewhat, as financial strains have intensified and housing demand appears to have fallen further.

I couldn't have said it better myself. Bottom line: it's getting worse.

Moreover, we face a risk that the problems in the housing market could spill over to personal consumption expenditures in a bigger way than has thus far been evident in the data. This is a significant risk since personal consumption accounts for about 70 percent of real GDP. These spillovers could occur through several channels. For example, with house prices falling, homeowners’ total wealth declines, and that could lead to a pullback in spending. At the same time, the fall in house prices may constrain consumer spending by changing the value of mortgage equity; less equity, for example, reduces the quantity of funds available for credit-constrained consumers to borrow through home equity loans or to withdraw through refinancing. Furthermore, in the new environment of higher rates and tighter terms on mortgages, we may see other negative impacts on consumer spending. The reduced availability of high loan-to-value ratio and piggyback loans may drive some would-be homeowners to pull back on consumption in order to save for a sizable down payment. In addition, credit-constrained consumers with adjustable-rate mortgages seem likely to curtail spending, as interest rates reset at higher levels and they find themselves with less disposable income.

Consumption spending was moderately above trend in the third quarter, and though I had built in some slowing for it in my October forecast, there are signs suggesting even more moderation over the next year or so. For example, although consumers will continue to receive support from gains in employment and personal income, they will also confront constraints because of the declines in the stock market and house prices, the tightening of lending terms at depository institutions, and higher energy prices.

First, note that Yellen admits the importance of mortgage equity withdrawal (MEW) for the current economy. In addition, she also admits the impact of declining wealth on personal consumption behavior which is negative. In short, the housing mess stands a chance of really hitting about 70% of the economy and that's a cause for serious concern.

Here is a chart of personal consumption expenditures from the latest GDP report.

Overall, PCEs were the same from July to August. But they have declined since then. The durable goods number is also cause for concern, as it has jumped around quite a bit.

Moreover, there are significant downside risks to this projection. Recent data on personal consumption expenditures and retail sales are not that encouraging. They have begun to show a significant deceleration—more than was expected—and consumer confidence has plummeted. Reinforcing these concerns, I have begun to hear a pattern of negative comments and stories from my business contacts, including members of our Head Office and Branch Boards of Directors. It is far too early to tell if we are in for a sustained period of sluggish growth in consumption spending, but recent developments do raise this possibility as a serious risk to the forecast.

Short version: Consumer spending is slowing and business leaders are worried. And well they should be.

Next up was Donald Kohn:

Central banks seek to promote financial stability while avoiding the creation of moral hazard. People should bear the consequences of their decisions about lending, borrowing, and managing their portfolios, both when those decisions turn out to be wise and when they turn out to be ill advised. At the same time, however, in my view, when the decisions do go poorly, innocent bystanders should not have to bear the cost.

In general, I think those dual objectives--promoting financial stability and avoiding the creation of moral hazard--are best reconciled by central banks' focusing on the macroeconomic objectives of price stability and maximum employment. Asset prices will eventually find levels consistent with the economy producing at its potential, consumer prices remaining stable, and interest rates reflecting productivity and thrift. Such a strategy would not forestall the correction of asset prices that are out of line with fundamentals or prevent investors from sustaining significant losses. Losses were evident early in this decade in the case of many high-tech stocks, and they are in store for houses purchased at unsustainable prices and for mortgages made on the assumption that house prices would rise indefinitely.

To be sure, lowering interest rates to keep the economy on an even keel when adverse financial market developments occur will reduce the penalty incurred by some people who exercised poor judgment. But these people are still bearing the costs of their decisions and we should not hold the economy hostage to teach a small segment of the population a lesson.

I love this paragraph. While paying lip-service to the idea of moral hazard, Kohn basically says, "the needs of the many out weight the needs of the few" (yes, I was a Trekkie). In other words, ignore what he said in the first paragraph and let the interest rate cuts begin.

Related developments in housing and mortgage markets are a root cause of the financial market turbulence. Expectations of ever-rising house prices along with increasingly lax lending standards, especially on subprime mortgages, created an unsustainable dynamic, which is now reversing. In that reversal, loss and fear of loss on mortgage credit have impaired the availability of new mortgage loans, which in turn has reduced the demand for housing and put downward pressures on house prices, which have further damped desires to lend. We are following this trajectory closely, but key questions for central banks, including the Federal Reserve, are, What is happening to credit for other uses, and how much restraint are financial market developments likely to exert on demands outside the housing sector?

Some broader repricing of risk is not surprising or unwelcome in the wake of unusually thin rewards for risk taking in several types of credit over recent years. And such a repricing in the form of wider spreads and tighter credit standards at banks and other lenders would make some types of credit more expensive and discourage some spending, developments that would require offsetting policy actions, other things being equal. Some restraint on demand from this process was a factor I took into account when I considered the economic outlook and the appropriate policy responses over the past few months.

An important issue now is whether concerns about losses on mortgages and some other instruments are inducing much greater restraint and thus constricting the flow of credit to a broad range of borrowers by more than seemed in train a month or two ago. In general, nonfinancial businesses have been in very good financial condition; outside of variable-rate mortgages, households are meeting their obligations with, to date, only a little increase in delinquency rates, which generally remain at low levels. Consequently, we might expect a moderate adjustment in the availability of credit to these key spending sectors. However, the increased turbulence of recent weeks partly reversed some of the improvement in market functioning over the late part of September and in October. Should the elevated turbulence persist, it would increase the possibility of further tightening in financial conditions for households and businesses. Heightened concerns about larger losses at financial institutions now reflected in various markets have depressed equity prices and could induce more intermediaries to adopt a more defensive posture in granting credit, not only for house purchases, but for other uses a well.

This is a really long-winded paragraph, isn't it?

Here's the short version:

1.) Everybody thought house prices would go up forever.

2.) Because everyone thought house prices would go up forever, lenders got really lax in their lending standards. If you had a pulse, you could get a loan (actually, both of my dogs were recently solicited for a mortgage)

3.) Oooops! Number 1 didn't happen.

4.) That means number 2 was a really bad and stupid idea.

5.) Because of number 2, lenders are not really thrilled about making new loans right now.

6.) In fact, lenders are buttoning down their hatches right now.

7.) In fact, if you want to get a loan, lenders will actually look at things like your credit score and payment history, rather than if you have a pulse.

8.) In fact, even if you have a decent credit score, it's stil going to be harder to get a loan largely because the two largest mortgage purchasers (Fannie Maw and Freddie Mac) are bleeding pretty badly right now.

Central banks have been confronting several issues in the provision of liquidity and bank funding. When the turbulence deepened in early August, demands for liquidity and reserves pushed overnight rates in interbank markets above monetary policy targets. The aggressive provision of reserves by a number of central banks met those demands, and rates returned to targeted levels. In the United States, strong bids by foreign banks in the dollar-funding markets early in the day have complicated our management of this rate. And demands for reserves have been more variable and less flexible in an environment of heightened uncertainty, thereby adding to volatility. In addition, the Federal Reserve is limited in its ability to restrict the actual federal funds rate within a narrow band because we cannot, by law, pay interest on reserves for another four years.

At the same time, the term interbank funding markets have remained unsettled. This is evident in the much wider spread between term funding rates--like libor--and the expected path of the federal funds rate. This is not solely a dollar-funding phenomenon--it is being experienced in euro and sterling markets to different degrees. Many loans are priced off of these term funding rates, and the wider spreads are one development we have factored into our easing actions. Moreover, the behavior of these rates is symptomatic of caution among key marketmakers about taking and funding positions, and this is probably impeding the reestablishment of broader market trading liquidity. Conditions in term markets have deteriorated some in recent weeks. The deterioration partly reflects portfolio adjustments for the publication of year-end balance sheets. Our announcement on Monday of term open market operations was designed to alleviate some of the concerns about year-end pressures.

The underlying causes of the persistence of relatively wide-term funding spreads are not yet clear. Several factors probably have been contributing. One may be potential counterparty risk while the ultimate size and location of credit losses on subprime mortgages and other lending are yet to be determined. Another probably is balance sheet risk or capital risk--that is, caution about retaining greater control over the size of balance sheets and capital ratios given uncertainty about the ultimate demands for bank credit to meet liquidity backstop and other obligations. Favoring overnight or very short-term loans to other depositories and limiting term loans give banks the flexibility to reduce one type of asset if others grow or to reduce the entire size of the balance sheet to maintain capital leverage ratios if losses unexpectedly subtract from capital. Finally, banks may be worried about access to liquidity in turbulent markets. Such a concern would lead to increased demands and reduced supplies of term funding, which would put upward pressure on rates.

Boy, he's a long-winded guy, isn't he?

OK -- here's the short version.

1.) Financial institutions are hording cash right now. Why? Because a lot of them are taking big hits to their capital.

2.) Financial institutions aren't thrilled about lending money to other financial institutions right now. Why? All of those write downs we've been hearing about indicate that a borrower might not be around in 90 days when a short-term loan comes due. This is called "counterparty risk above."

3.) Financial institutions are really concerned about their own capital positions right now. Why? Because chances are they bought some of the sub-prime crap out there and they'll have to write down their assets in the near future. Therefore, they're hoarding cash. This is where the phrase. "the ultimate size and location of credit losses on subprime mortgages and other lending are yet to be determined" comes into play.

4.) The Fed really can't do much about this. Why? It doesn't matter how much cash you have if you don't want to lend it to somebody. But the Fed will try anyway by flooding the market with as many dollars as possible. Hey -- at least it's something, right?

And finally, we have Bernanke's speech:

With respect to household spending, the data received over the past month have been on the soft side. The Committee will have considerable additional information on consumer purchases and sentiment to digest before its next meeting. I expect household income and spending to continue to grow, but the combination of higher gas prices, the weak housing market, tighter credit conditions, and declines in stock prices seem likely to create some headwinds for the consumer in the months ahead.

Core inflation--that is, inflation excluding the relatively more volatile prices of food and energy--has remained moderate. However, the price of crude oil has continued its rise over the past month, a rise that will be reflected in gasoline and heating oil prices and, of course, in the overall inflation rate in the near term. Moreover, increases in food prices and in the prices of some imported goods have the potential to put additional pressures on inflation and inflation expectations. The effectiveness of monetary policy depends critically on maintaining the public’s confidence that inflation will be well controlled. We are accordingly monitoring inflation developments closely.

The incoming data on economic activity and prices will help to shape the Committee’s outlook for the economy; however, the outlook has also been importantly affected over the past month by renewed turbulence in financial markets, which has partially reversed the improvement that occurred in September and October. Investors have focused on continued credit losses and write-downs across a number of financial institutions, prompted in many cases by credit-rating agencies’ downgrades of securities backed by residential mortgages. The fresh wave of investor concern has contributed in recent weeks to a decline in equity values, a widening of risk spreads for many credit products (not only those related to housing), and increased short-term funding pressures. These developments have resulted in a further tightening in financial conditions, which has the potential to impose additional restraint on activity in housing markets and in other credit-sensitive sectors. Needless to say, the Federal Reserve is following the evolution of financial conditions carefully, with particular attention to the question of how strains in financial markets might affect the broader economy.

OK -- here's the translation:

1.) People aren't spending as much because food and gas prices are rising.

2.) The financial markets aren't doing that well and people are noticing. That is adding downward pressure to the markets.

What's really important here is all of the Fed governors have noticed the credit market is in terrible shape. That's the common theme through all of these speeches. And the problems in the credit market were caused by housing -- which isn't going to get better anytime soon. And finally, these problems are starting to negatively impact consumer sentiment and spending.

In short, the Fed is actually paying attention to the economy. The problem is will a rate cut be enough? I've said this over and over again, but the central problem isn't liquidity: it's confidence. When no one has any confidence that a borrower will be around in 90 days, it's difficult to lend money even in the short term. And cutting rates won't do squat about that.