Last Friday ECRI spokesman Lakshman Achuthan appeared on CNBC, CNN and Bloomberg television to defend his firm's 5 month old recession call. In the face of almost universal agreement that economic data has improved in the last few months, Achuthan insisted that it was beyond dispute that the real indicators had weakened, saying:

Since our recession call five months ago, the definitive, hard data used to determine official recession dates have gotten worse, not better, despite the consensus view that things have been improving. Okay? Since we made that call in late September, not a forecast, just looking at the incoming data.... those [are] key, hard facts. Nobody can get away from these no matter what you try to do.....I call Bullshit.

.... the hard data -- not a forecast, these are facts -- in plain English, economic growth is at its worst reading since early 2010. We are not cherry-picking the data. This is what is used to officially date the business cycle. They're the official, specific determinants of the business cycle.

.... the continued weakening in economic growth is consistent with our recession call from five months ago.

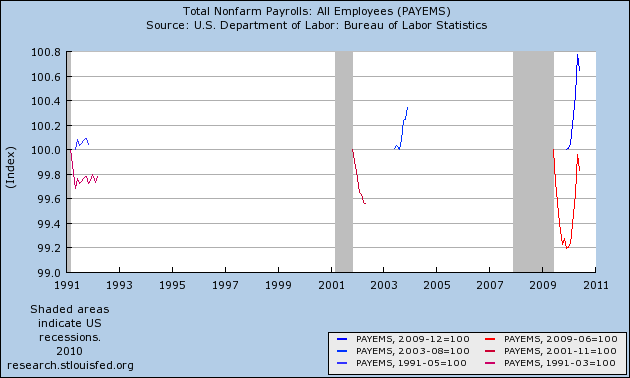

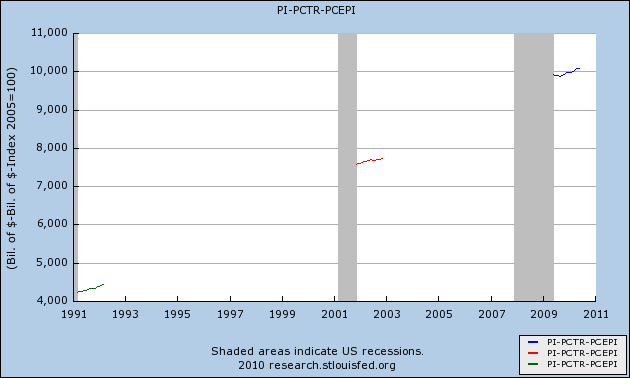

Achuthan based his argument on the performance of GDP and also the NBER's coincident measures of recession vs. expansion -- output, sales, income, and jobs. He also rightly noted that the monthly payrolls report actually lags slightly (note: specifically, it has always lagged real retail sales, which turn first), thus he focused on industrial production, sales, and income, saying that these as well as the GDP figures were hard data, not forecasts, and they were getting worse.

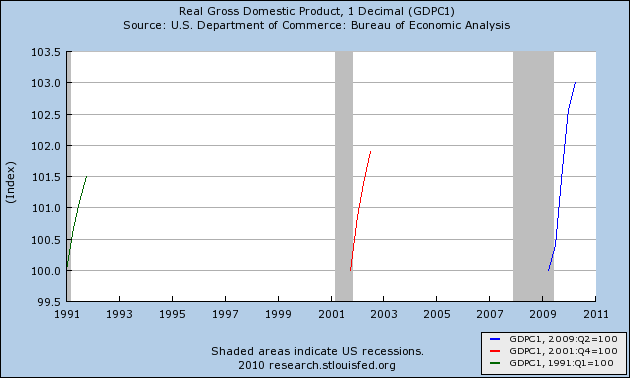

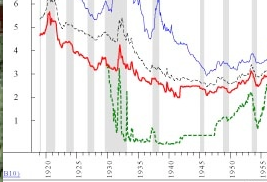

So here is a graph of GDP, normed at 100 at the bottom of the great recession:

Does that look like it's getting worse to you?

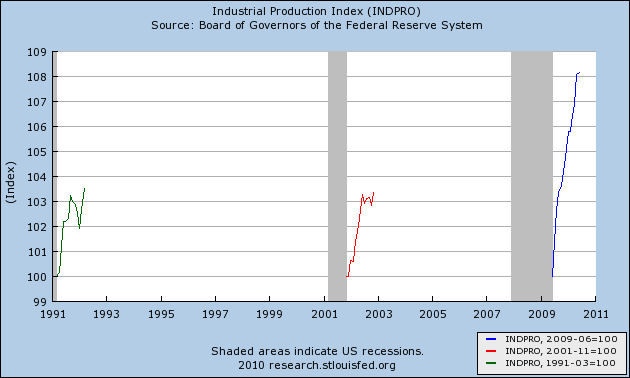

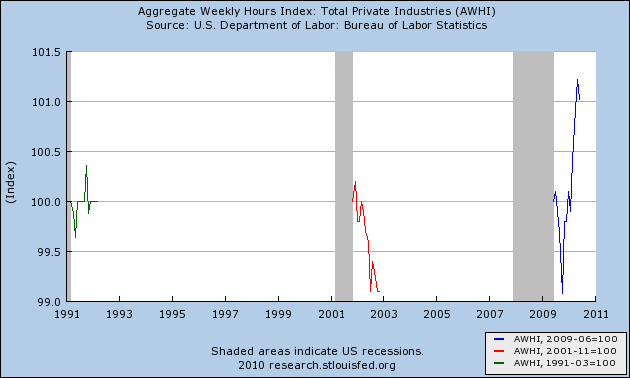

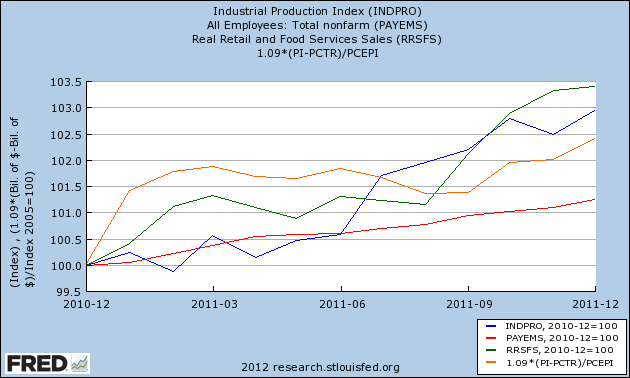

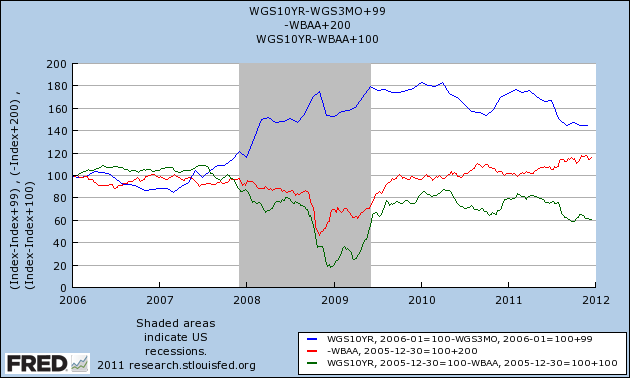

Now, here is a graph of industrial production, real retail sales, and real disposable personal income, averaged together, also normed at 100 at the bottom of the great recession:

Does that look like it's getting worse to you?

In fact, the real coincident data doesn't look like it's getting worse because it's not getting worse!

Achuthan's argument was based entirely on the second derivative of the coincident indicators. In other words, they're getting better, but they're getting better at a worse rate. Not only that, instead of relying on real-time month over month or quarter over quarter data, his argument was based on year over year trends.

Frequently it is necessary to use YoY data because much data is seasonal (e.g., housing sales, rail carloads). Other times it is useful to describe longer term trends by smoothing out the data. But where seasonally adjusted data exists, the use of YoY trends badly lags turning points -- exactly the opposite of what ECRI claims to be doing. And it makes a crucial difference in analysing their argument.

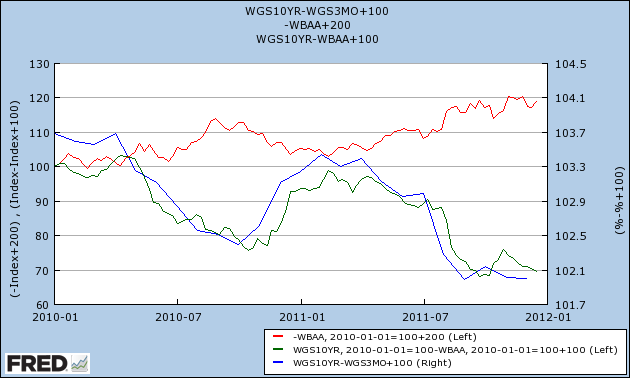

To show you how, let's first look at YoY% growth in GDP, a graph used by Achuthan:

This seems to support ECRI's claim that the coincident indicators are getting worse (although, as others have already shown, similar declines have happened as recently as 1987, 1993, and especially 1996 without demonstrating any imminent recession).

Now let's look at the same data, not YoY but quarter over quarter:

The real-time non-lagging GDP data shows improvement since the dismal first quarter of 2011.

Finally, let's compare the two. In the graph below, quarter over quarter GDP growth, annualized, is again shown in red exactly as above, and compared with the YoY% GDP growth in blue:

It is crystal clear that the red series of q/q GDP change turned first before and after both the 2001 and 2008 recessions. And yet Achuthan is basing his case that we are on the cusp of a recession not on the more forward looking red q/q series but on the lagging blue YoY series!

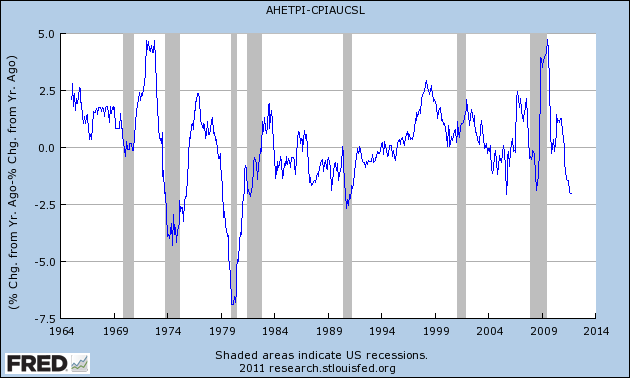

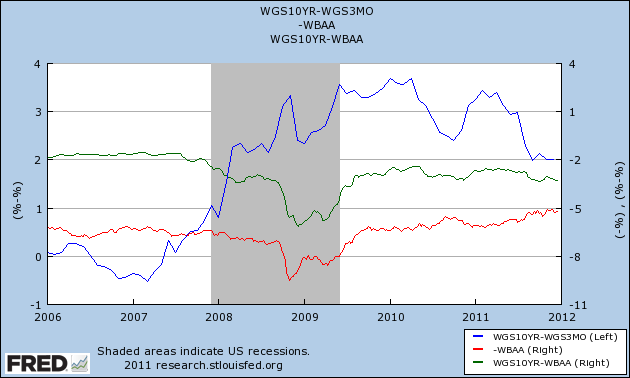

Let's do the same thing with sales (blue), output (red), and income (green). First, here's the graph of YoY% change

All of these show a decline in the second derivative, in the case of real disposable income, all the way to zero.

Now here is the same data, not YoY, but month over month (added together for simplicity):

Again, quite a different picture emerges. Last spring in particular was weak, but there has been improvement since then.

This, then, is the core of the argument Achuthan made: we're going into a recession because, after a stall last spring, the rebound since hasn't been as strong as the months that immediately preceded the stall.

This is as backward-looking an argument as can be, and hardly something I would expect from a group that prides itself on its forward looking indicators. Let me be more blunt: contrary to Achuthan, "the definitive, hard data used to determine official recession dates" by the NBER are not the YoY lagging metrics he relied upon, but rather the month over month and quarter over quarter metrics I have compared them with above. They are not "getting worse" as claimed by Achuthan, but improving as I have shown.

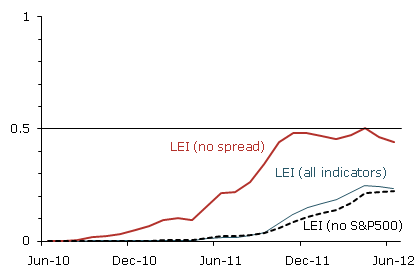

In fact during the Bloomberg and CNN interviews, leading indicators weren't mentioned at all. In response to a direct question during the CNBC interview, there was only one brief mention of leading indicators "in the aggregate" still supporting ECRI's call, with no further elucidation.

This is a severe problem with ECRI's black box methodology. Since he doesn't want to give away any of his firm's secrets, he is reduced to making his public argument by relying on lame lagging data.

With gas prices nearing $4 a gallon already, ECRI may yet get their recession before the end of 1H 2012, but if they do it won't be for the reasons cited by Achuthan. As I pointed out yesterday, there's is a very good bearish case to be made, based on a consumer who is probably near exhaustion, and ECRI does apparently believe in that argument, based on the headline to a proprietary article on their site. Too bad Achuthan didn't actually make that argument, and couldn't show why he believes it will prove correct.

the Death Star.

the Death Star.