As Calculated Risk pointed out yesterday, the ISM manufacturing report was an upside blowout, the strongest such report in several decades by some measures (the contrary "poor analysis" mentioned by CR was almost certainly the spin by the Doomorons at Zero Hedge. Google it if you feel you must). And Bonddad and I have separately written recently that the manufacturing sector has been exceptionally strong.

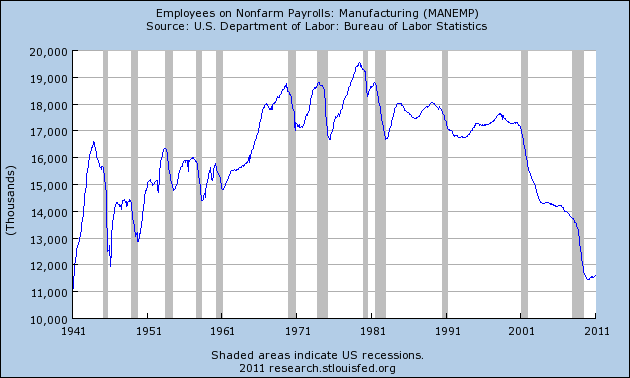

An important question is, how much does that translate to in terms of jobs? The ISM report is a diffusion index, meaning it measures expansion vs. contraction. Any number above 50 in any of its indexes means expansion, and visa versa. But like any data, it has shortcomings. All else being equal, with a population increase from 200 million to 300 million, an equivalent reading ought to suggest 50% more monthly hiring in the latter period than the former. But on the other hand, we know that due to efficiency and offshoring, the number of persons employed by manufacturing has fallen by 40% since the peak in 1979, as shown in this graph:

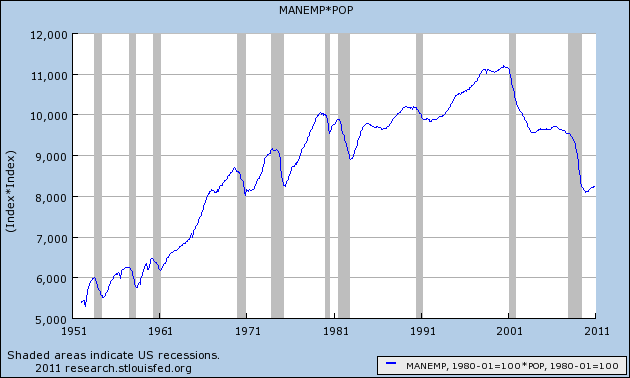

These crosscurrents suggest that the "real" effect of an equivalent ISM number on employment over time would look something like this graph, in which the number of manufacturing employees is multiplied by population (with 1979 = 1):

(BTW, admittedly this is not a true representation, since we would want to visit an alternate universe where either population was held constant or there were no efficiency gains or offshoring, but presumably you get the drift)

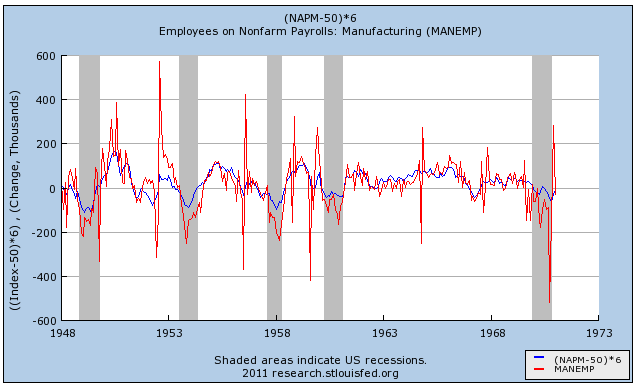

When I went to look at the data, I expected there to be both more hiring and firing over time, due to population increases, compared with equivalent ISM readings. That wasn't the case. In fact, since the ISM started publishing data in 1948, up until about 1999, the amount by which an ISM reading exceeded 50, multiplied by 6 (thousand), gave you an excellent idea of what manufacturing job gains were during the same month. Here is the period of 1948 through 1970:

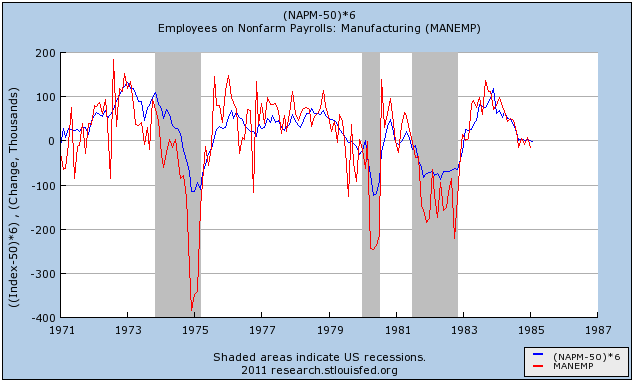

Here it is for the severe recessions of the 1970s and 1982:

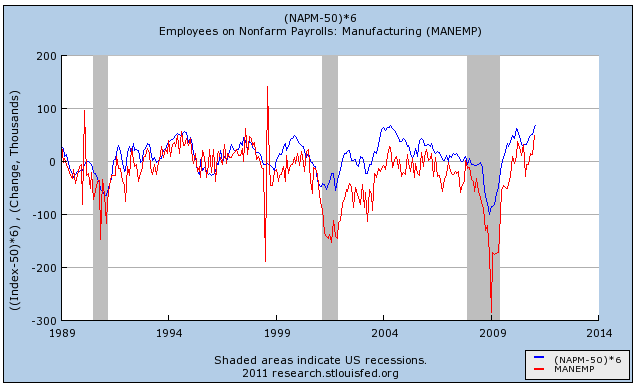

And here it is from 1989 to the present. Note that the red line (manufacturing jobs gained/lost per month, in thousands) no longer keeps up with the blue line (the ISM manufactuing index with equilibrium reset from 50 to 0 for easy comparison) after 1998:

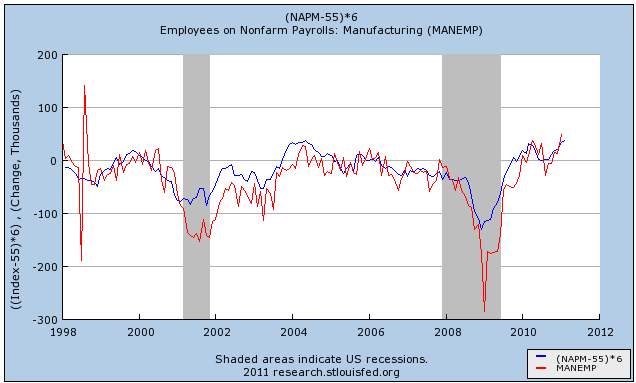

In fact, there is an excellent fit since 1998, but it involves resetting the equilibrium point at 55 instead of 50. In other words, subtract 55 (instead of 50) from the ISM reading, and multiply by 6 (thousand) and for the last 10+ years that will give you a very close approximation to the number of manufacturing jobs added that month:

February's ISM manufacturing index reading was 64.5. This is 9.5 above 55, multiplied by 6000, tells us that about 57,000 manufacturing jobs were probably added last month. This is an excellent number compared with the last decade, but before 1999 it would have suggested an increase of 87,000 manufacturing jobs. (Note: using a different analysis, Calculated Risk estimates ~+60,000 manufacturing jobs were added in February. Great minds think alike, etc.)

(As a side note, using the ISM manufacturing employment sub-index yields the same result).

I'm not sure what the underlying fundamental reason for the change is. There certainly were both offshoring and efficiencies taking place before 1999. China did not accede to the WTO until 2001, so that is an incomplete explanation at best. It is also possible, given the last few months' strong manufacturing employment data, that the decade long aberration is abating. Finally, relative strength in manufacturing jobs, even though substantial, is still only a minority part of the overall jobs picture. I'll deal with construction, government, and non-government services separately. In that regard, the ISM non manufacturing index will be released tomorrow.