- by New Deal democrat

As an initial matter, I disagree that this qualifies as a "jobless" recovery. Beginning six months ago, the economy has added 600,000 or 1.3 million non-census jobs, depending on which survey you use. On its face that is simply not "jobless" as the term was used after the last two recessions, when it described an extended period where GDP grew but jobs actually continued to be lost.

But let's go to the heart of the matter. If this were actually a "realignment", we should expect to see a change in movement between the various types of work, and in particular, a move away from manufacturing into other types of work. One sort of job, having risen, would start to decline. Another, having declined, would start to rise. But - aside from one obvious type of job - that is simply not the case.

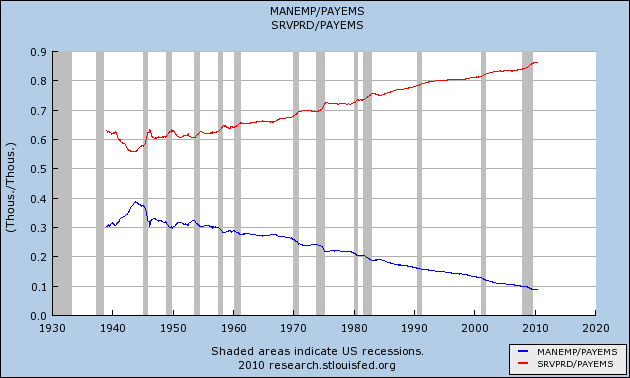

The following graph shows manufacturing jobs (blue) and service jobs (red) as a percent of total employment since World War 2:

As you can see, as a percent of total employment, service jobs have been rising, and manufacturing jobs have been declining throughout the entire 70 year period. The recent recession and recovery barely even creates a blip in the trends.

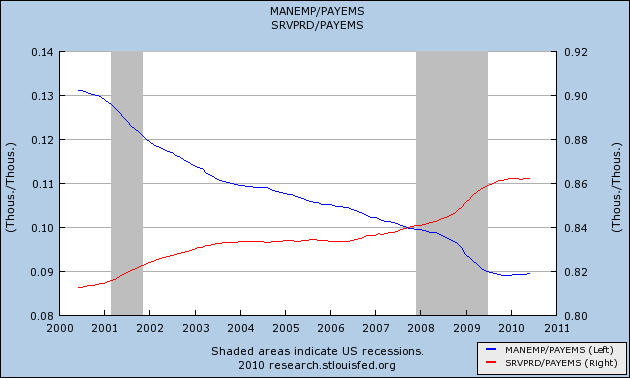

Now let's look at a close-up of the same graph, focusing on the last 10 years (note I have moved the measure of service jobs to the right axis to better show the contrast):

Now let's look at a close-up of the same graph, focusing on the last 10 years (note I have moved the measure of service jobs to the right axis to better show the contrast):

At most, there was a 1 year, 1% deviation. Simply put, the recent recession and recovery haven't made a dent in the long term trend. As a percent of the total workforce, service jobs have continued to rise, and manufacturing jobs have continued to fall -- just as they did for the last two recessions and following "jobless recoveries."

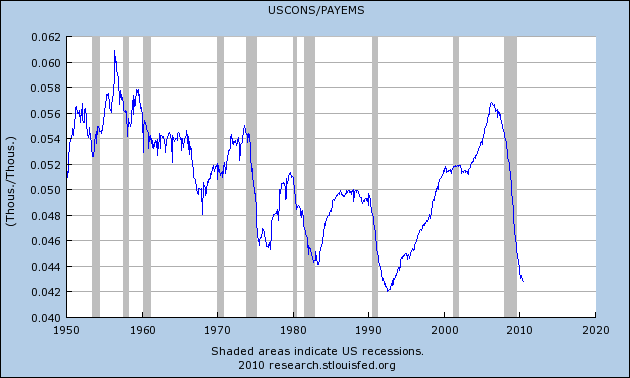

The situation is completely different when one looks at a graph of construction jobs as a percent of total employment:

The above graph clearly shows that this ratio has collapsed as a result of the bursting of the housing bubble. About a third of all construction workers have been laid off, and the percentage of workers in that area has fallen to a near post WW2 low. So in the sense that this recession caused construction employment to crater, yes there has been a job realignment. But we already knew that.

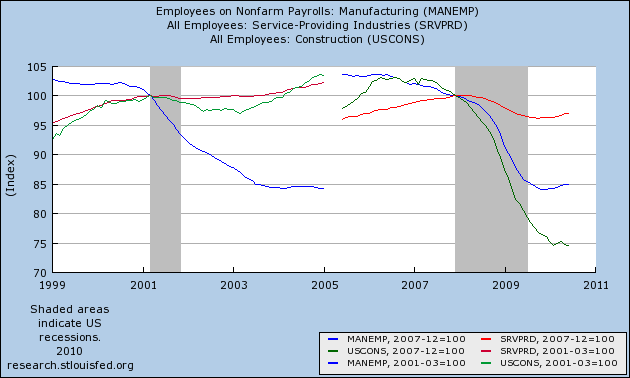

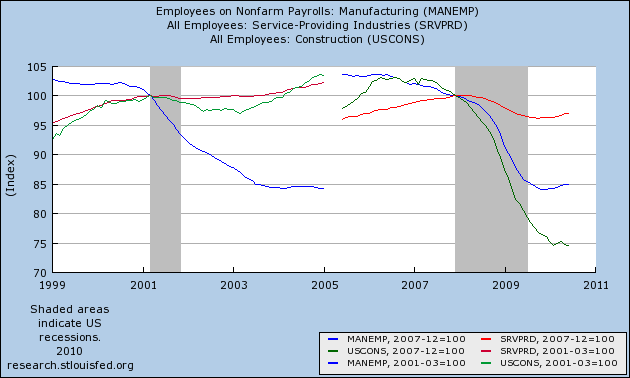

Now let's put all of the above information together. The following graph shows the decline from peak of manufacturing jobs (blue), service jobs (red), and construction jobs (green) in the 2001 recession and also in the "Great Recession":

In fact, the "Great Recession" did not hit manufacturing employment significantly harder than did the minor recession of 2001. To the contrary, it has been construction jobs and service jobs that have been hit very hard in the recent recession compared with the 2001 recession. So I must respectfully disagree with my co-blogger. At least as far as the "realignment" thesis regards manufacturing employment, I believe it must be rejected.

In his follow-up post yesterday, Bonddad does note that construction jobs in particular, as well as some service sectors, have taken a big hit, so in that sense we agree. But for that loss to qualify as a "realignment" of the labor force, I would want to see evidence that it has been productivity gains in construction or services that have led to the continuing decline. I do not believe there is such evidence. To the contrary, residential construction in particular has fallen 75% from peak, and at the trough last summer, real retail sales were 10% off peak. As neither construction nor service jobs have fallen as much in percentage terms, I do not think those losses can be called realignments -- again, with the exception that nothing like last decade's construction bubble is likely to be seen any time soon.

But Bonddad's theory does raise another very critical issue: to what extent have manufacturing job losses over the longer term been caused by productivity vs. outsourcing? This seems impossible to quantify exactly with publicly available data, but I do believe we can put one outside limit on it. I will address that in another post.

Now let's put all of the above information together. The following graph shows the decline from peak of manufacturing jobs (blue), service jobs (red), and construction jobs (green) in the 2001 recession and also in the "Great Recession":

In fact, the "Great Recession" did not hit manufacturing employment significantly harder than did the minor recession of 2001. To the contrary, it has been construction jobs and service jobs that have been hit very hard in the recent recession compared with the 2001 recession. So I must respectfully disagree with my co-blogger. At least as far as the "realignment" thesis regards manufacturing employment, I believe it must be rejected.

In his follow-up post yesterday, Bonddad does note that construction jobs in particular, as well as some service sectors, have taken a big hit, so in that sense we agree. But for that loss to qualify as a "realignment" of the labor force, I would want to see evidence that it has been productivity gains in construction or services that have led to the continuing decline. I do not believe there is such evidence. To the contrary, residential construction in particular has fallen 75% from peak, and at the trough last summer, real retail sales were 10% off peak. As neither construction nor service jobs have fallen as much in percentage terms, I do not think those losses can be called realignments -- again, with the exception that nothing like last decade's construction bubble is likely to be seen any time soon.

But Bonddad's theory does raise another very critical issue: to what extent have manufacturing job losses over the longer term been caused by productivity vs. outsourcing? This seems impossible to quantify exactly with publicly available data, but I do believe we can put one outside limit on it. I will address that in another post.