I. The role of Fear is the missing element in analyses of the recent downdraft

By April of this year, virtually every economic indicator pointed to recovery: not only had GDP regained nearly 3/4's of its 2008-09 loss, but industrial production, manufacturing, and consumer purchasing were on a roll. Beyond that, early indicators by way of temporary hiring had given way to strong hiring in the general economy. Even real income had picked up slightly. On Monday an article at CNBC's website confirmed my writing last week that:

Despite all the gloom and doom about the US economy, the private sector actually created 620,000 jobs over the past seven months, far faster than in the previous two recessions. generating between 200,000 and 300,000 new jobs (excluding census workers) each month.Then, suddenly, it seemed like the bottom fell out. GDP in the second quarter is likely to ultimately be tallied well under 2%. Industrial production in June barely budged. Manufacturing cooled off. Retail sales fell over 1% in May and another 0.3% in June. Even worse, non-census hiring came to a screeching halt: about +20,000 in May, -21,000 in June, and again +12,000 in July. Talk of a "double-dip" second downturn, which had all but disappeared into the shadows in April, returned with a vengeance by July, with prominent bears like David Rosenburg proclaiming that there was better than a 50/50 chance that a second leg down was to ensue. Permabears like Mish crowed.

It wasn't as if some Doom Fairy had come along and waved her black magic wand over the economy -- there were real reasons for the downturn in some of the statistics. Oil briefly at almost $90 equated to 4% of the GDP, historically the tipping point between expansion and oil shock induced recession. The explosion and sinking of BP's well in the Gulf of Mexico was an economic disaster for the Gulf of Mexico secondarily to an environmental catastrophe. The expiration of the ill-conceived $8000 housing credit caused demand to crater, subtracting about 100,000 housing starts a month, and leading to more construction and real estate industry layoffs. The failure of Congress to pass adequate and timely relief for state and local budgets meant that nearly 100,000 layoffs that would have happened last year, and could have been averted again this year, in fact took place in June and July.

But the abrupt halt in private sector hiring and cliff-diving decline in consumer spending in May defy explanation based just on the above list. A whole host of indicators all pointed to more robust job growth -- ISM manufacturing, temporary help hiring, durable goods orders, real retail sales, and for good measure the Conference Board's (which publishes the LEI) Employment Trends Index:

Instead, something happened in late April and early May to make employers and consumers alike suddenly freeze in their tracks. That something was fear.

And that is where Pavlov's dogs come in.

II. Sometimes, they *do* ring a (psychological) bell at tops

As I said last week, *why* there was such a sudden downdraft in the economy is something that economics itself does not explain well. For that, economists need to take a walk down the hall or to the faculty lounge and have a chat with their colleagues in the psychology department. I contend that what happened in April and May is a classic case of "classical conditioning."

Classical Conditioning is the type of learning made famous by Pavlov's experiments with dogs. The gist of the experiment is this: Pavlov presented dogs with food, and measured their salivary response (how much they drooled). Then he began ringing a bell just before presenting the food. At first, the dogs did not begin salivating until the food was presented. After a while, however, the dogs began to salivate when the sound of the bell was presented. They learned to associate the sound of the bell with the presentation of the food. As far as their immediate physiological responses were concerned, the sound of the bell became equivalent to the presentation of the food.Classical conditioning doesn't just happen in the lab. Here is a perfect example, by John Cole of the blog "Balloon Juice" asking his dogs if they want to go for a w-a-l-k:

....

In Pavlov's experiment, the sound of the bell meant nothing to the dogs at first. After its sound was associated with the presentation of food, it became a conditioned stimulus. If a warning buzzer is associated with the shock, the animals will learn to fear it.

Not only do Cole's dogs, like most doggie pets, go just about berserk when their owner says the word w-a-l-k, but Cole further wrote that

because I foolishly previewed the video and the piglets overheard it, I have two dogs dancing around my feet who want to go for walks.That, dear readers, is classical conditioning. The dogs associated the word with the act. And of course, it's not just dogs, humans react to classical conditioning as well (want to bet Cole reacted to his pets' whining by actually taking them for walks?). For example, just last week it was reported that

The first time you burn your fingers by touching a hot stove you get the lesson to avoid doing it in the future. And now scientists are trying to know what exactly goes on in the brain that triggers such avoidance behaviour in a study on fruit flies.Just as Pavlov's dogs learned that a buzzer meant a painful shock, so most people don't have to touch a hot stove twice to learn to avoid it.

III. Classical conditioning and the Panic of 2008

As is often the case, Prof. Paul Krugman said it best: "This is not your father's recession -- it's your grandfather's."

The Panic of 2008, or the "Great Recession", was the first deflationary bust since 1938. That's 72 years ago and no economic decision-makers either on the corporate side, or meaningfully on the consumer side, recall that recession. Deflationary panics are a new event to all of us. Or, in psychological terms, a new stimulus, to which economic actors responded. Back then, I wrote a piece called Black September, showing how in large part it was panic -- by President George Bush, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, Rep. Barney Frank and Sen. Christopher Dodd among others -- who day after day told several hundred million Americans that their paychecks were going to bounce if they didn't give $700 million to Wall Street immediately -- that created a corresponding abrupt halt in spending by consumers. As one auto dealer said at the time:

On about September 10, we saw our business fall off 30-35%.Calculated Risk accurately surmised at the time that tens of millions of American families had discussions around the dinner table amounting to "Wow, this is bad. Let's make sure our money is safe, and watch our expenditures." and thereby made the recession worse.

Not only did consumer spending fall off a cliff beginning in September 2008, employers were caught flat-footed as well. As shown in this graph of insider buying and selling from Barron's in early 2009, while insiders had at times sold during 2008, they were also significant buyers of their own company's stock at several of the temporary bottoms in the market that predated the September - October crash:

So, when the sudden collapse in consumer spending hit, employers panicked as well. As one observer put it shortly after, "If employers needed to lay off 20, they laid off 40 just to be sure."

This was the equivalent of both employers and consumers hearing a shouted warning just before they touched a hot stove. They reacted immediately and drastically to the "buzzer" (the panic in their public officials) that did actually turn out to precede very painful stimuli (a collapse in consumer demand, and over half a million layoffs a month for over half a year).

What both employers and consumers learned in September 2008 and immediately thereafter, was to be alert for signs of a "Credit Freeze!" because if one occurred, very bad things were about to happen.

IV. April 2010

Fast forward to springtime this year. The recovery is proceeding in V-shaped fashion in both GDP and manufacturing terms. While the consumer end started late, nevertheless since late 2009, both real income and then jobs started to increase. So well was the economy doing by the end of the first quarter that all the signs were that the hiring of March and April was likely to continue, as consumer spending and business capital purchases both moved forward.

But in the background, another event began to unfold. Since the minor crisis in Dubai last December, bond yields and stock prices began to move in tandem as investors began to worry about sovereign defaults. The bears looked around for who might be the next sovereign to run into trouble, and the answer wasn't difficult to discern: Greece.

In March the Greek crisis began exploded onto the global financial news with news of rioting that included several deaths. Worse, as bear raids were mounted not just on Greek bonds, but on Spanish, Portuguese, and other bonds as well, some of the leading European politicians and financial officials resembled mirror images of Bush et al from September 2008. For example, by April 19,

German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble [ ] pleaded with his country's citizens to back a joint EU-IMF bail out for Greece worth up to €45bn (£40bn), warning that failure to act risks a financial meltdown.Then, most infamously, Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany, foolishly ratcheted up panic by proclaiming publicly that

"The current crisis facing the euro is the biggest test Europe has faced in decades. It is an existential test and it must be overcome ... if the euro fails, then Europe fails."A second round of bank failures, and even widespread sovereign defaults in Europe were openly discussed in the media.

It was against that background that the additional blows of the BP Gulf of Mexico disaster that began with the explosion of April 20. Ten days later, the $8000 mortgage credit expired, and by May 19 purchase mortgage applications had falled to a 13 year low. On May 6, there was a 10 minute "flash crash" of 1000 points on the Dow Jones Industrial Average -- which has still not been fully explained. The ECRI weekly leading indicator -- which had gained notoriety with the group's gutsy recovery call in March 2009 -- plunged back into negative territory, and was widely reported in the media. And states and localities warned about draconian cuts of personnel and services in summer if Congressional emergency funding didn't come through.

It is important to note that, except for the BP disaster, none of the actual economic consequences of any of these items were actually being felt yet. But what employers and consumers thought they were hearing -- especially due to the Euro crisis -- was a warning that we were about to endure another Credit freeze! To use the "hot stove" analogy, they heard a warning that they were about to touch one again. Once burned, twice shy.

And they reacted the way they had been classically conditioned by September 2008 to act. Employers froze hiring plans immediately. And consumers cut back on spending, retrenching in fear of another round of 100,000s of layoffs. Only that explains the precipitous halt in employer hiring, and consumer spending, that took place immediately in May and continued in June.

V. Sometimes hearing the word w-a-l-k doesn't mean you are going for a walk

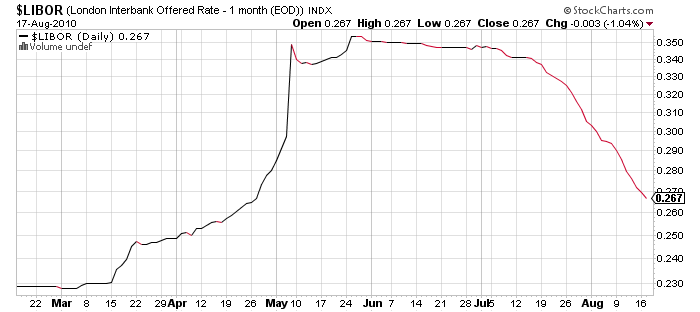

Just as John Cole didn't actually plan on taking his dogs for a walk when he played back the video of his dogs' reactions to his using the word, so the Greek crisis didn't actually metasticize into a "credit freeze." The European Union made credible guarantees about their backing of the Euro. Libor - a measure of bond market stress - which rose dramatically in the March - early May period, declined more than half of that since, a sign that most of the stress has passed:

And most of the other crises have passed as well. BP finally capped its well in mid-July. Mortgage applications bottomed in mid-July as well, and have ever so slightly improved in the four weeks since. The DJIA rose 10% from its early July bottom. Congress passed at least some relief for the states. Only Oil, still ranging between $70-$82 a barrel, remains an unresolved drag on the economy.

There are signs that consumers have come back out of their cave. July retail sale were up 0.4%, the first gain in real, inflation adjusted retail sales since April. Housing permits rose slightly in June, and then fell again slightly back to May's levels, in July. It seems that consumers have begun to decide that the "credit freeze!" may not happen again after all. On the employer side, hiring of temporary help has resumed, as the American Staffing Associaton's index just reached a two-year high.

Of course, the fear of a steep downturn could yet be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Recall my quip above. When he played back his video, John Cole hadn't intended to take his dogs for a walk, but the dogs thought otherwise. He may well have given in and taken them for a walk after all.

On the other hand, if he didn't, Cole's dogs probably settled back down. Similarly, while the loss of 100,000 in housing starts is a blow, it need not create a "double-dip", and states and localities may be able to pull back from the worst with the new infusion of federal cash (together with improving tax receipts). A near zero GDP for the third quarter looks baked in the cake. But if there isn't another "exogenous event" like the BP catastrophe in the next couple of months, and if there are no renewed fears of a "credit freeze!" in Europe or elsewhere, consumers may gradually resume their spending habits from before May, and private employers may resume hiring at spring's pace.