The United States remains firmly in an economic recession in spite of economic growth figures to the contrary, a leading economist has warned.

Merrill Lynch’s David Rosenberg, the first economist from a major bank to declare a US recession was underway back in early January, argues that recent unemployment figures show yet more evidence that the US economy is a deep recession.

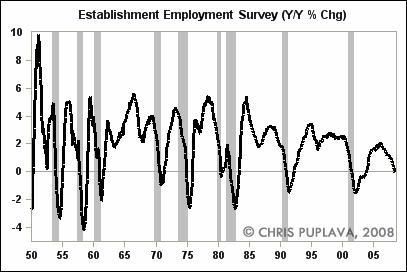

Pointing to last week’s news that employment has now declined for six months in a row, Mr Rosenberg, Merrill’s chief North American economist, says that “at no time in the past 50 years has this happened without the economy being in an official recession.”

.....

However he argues that this is only a matter of time, given that all four recession determinants “have peaked and rolled over.”

He points to widespread decline in economic activity, noting that real sales in manufacturing and retail, employment, industrial production, and real personal income – the four determinants – are all way below their peaks.

Looking at the numbers, Rosenberg is dead-on accurate.

Anyone who is currently arguing that we are not in a recession is simply proving how little they know about economics. The underlying facts and figures are clearly pointing otherwise.

There is one measure that the "there is no recession" (or as Barry Ritholtz calls them the Pervasive Pollyannas of Prosperity or PPP) crowd points to: we have not have two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. Therefore, we're not in a recession. The official organization that dates recessions (the NBER) answers that observation thusly:

A: Most of the recessions identified by our procedures do consist of two or more quarters of declining real GDP, but not all of them. Our procedure differs from the two-quarter rule in a number of ways. First, we consider the depth as well as the duration of the decline in economic activity. Recall that our definition includes the phrase, "a significant decline in economic activity." Second, we use a broader array of indicators than just real GDP. One reason for this is that the GDP data are subject to considerable revision. Third, we use monthly indicators to arrive at a monthly chronology.

In other words, using one statistic to describe a system as complex as the US economy is pointless. What we're really looking for is a fairly widespread decline in activity that lasts a fairly long time. To that end, the NEBR uses the following criteria

The committee places particular emphasis on two monthly measures of activity across the entire economy: (1) personal income less transfer payments, in real terms and (2) employment. In addition, we refer to two indicators with coverage primarily of manufacturing and goods: (3) industrial production and (4) the volume of sales of the manufacturing and wholesale-retail sectors adjusted for price changes.

Why are these particular indicators important? Let's look at each one in detail.

1.) Personal income tells us if there is wage pressure in the economy. Wage pressure occurs at full employment which is a sign of an economic expansion. When unemployment is low, people can go to their boss and say, "I want a raise, and you'll give me one because you can't find a replacement for me that will work at a lower rate." A lack of wage pressure indicates there is slack in the labor market, which in turn tells us we're not at full employment, which in turn tells us things might not be that good.

Transfer payments are the eco-geeks way of saying "government assistance." In other words, the stimulus checks that went out over the last few months don't count. All that being said, here is a chart from Econoday of personal income's year over year change:

But, remember -- that nice big jump doesn't count (The same thing happened a few years ago when Microsoft declared a special dividend). As Marketwatch noted:

Personal incomes rose 1.9% in May, the largest gain since September 2005, when insurance payments from hurricane damage flooded into bank accounts. The increase was close to the 1.5% gain expected by economists surveyed by MarketWatch.

Real disposable incomes (after taxes and adjusted for inflation) increased 5.3%, the biggest increase since 1975, when the government also sent out rebate checks.

Excluding the impact of the rebates and inflation, real disposable incomes were flat.

In other words, without government help, incomes didn't increase at all thanks to the stimulus checks. That tells us there is no wage pressure, indicating we're nowhere near full employment.

Now let's look at personal consumption expenditures (adjusted for inflation) to see how healthy consumers feel.

That charts tells us one thing. Consumers have not been feeling healthy about spending since the end of last summer. In fact, they have continually decreased their consumption expenditures over the last year. That is a very negative sign, especially for an economy that is dependent on consumer spending for 70% of its growth.

2.) Employment growth tells us if business is feeling healthy or not. If business sees blue skies on the horizon they add employees. If business sees storms, they "downsize" (or fire people).

To that end, business sees a lot of storms ahead.

The year over year rate of job growth has been dropping for the last two years. In addition:

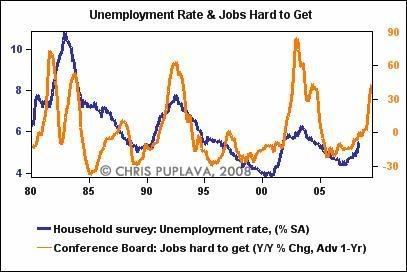

The unemployment rate has been increasing for a year and a half. That is definitely a very bad development.

But there are deeper issues in the employment report which are highlighted very nicely in a recent article by Chris Puplava. He writes at a website called Financial Sense.

The chart above places the year over year change in employment in long-term perspective. The point is clear: every other time the year over year chart has been at current levels, the US economy has been in a recession.

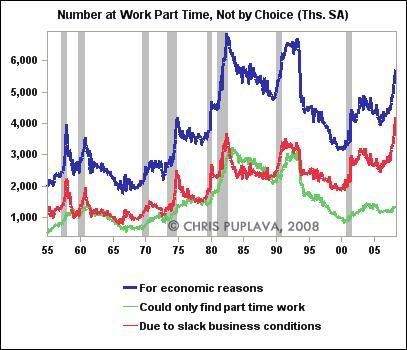

The chart above shows the number of people who have had their employment hours cut back involuntarily. In other words, the business where they work is decreasing the number of hours each person works. Again note that when this statistic was at similar levels in 1980 and 1990, the country was in a recession.

The chart above shows that the number of people who thing jobs are hard to get is increasing at a quick pace. That is helping to lower consumer sentiment and confidence, which in turn is lowering personal consumption expenditures.

So on the employment front we are clearly in a downtrend. Several important indicators are at levels usually seen during recessions.

3.) I explained the current situation regarding industrial production in this article. None of the indicators has changed sign I wrote that article. The short summation is this: national industrial production has been decreasing since the last quarter of 2007. Capacity utilization is decreasing, indicating we're using less of our manufacturing capability, and several regional indexes are showing contraction.

Regarding the manufacturing sector, there is a new development that is troubling. Exports have been one bright spot of the current economic situation. However, several regions of the world are now reporting a slowdown:

Singapore cut its 2008 growth forecast for a second time this year, joining its Asian neighbors in signaling a deeper slowdown.

The island's economy will expand between 4 percent and 5 percent, from an earlier estimate of 4 percent to 6 percent, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said yesterday. Growth was 7.7 percent in 2007.

.....

Governments from South Korea to Thailand have lowered their 2008 growth forecasts since the start of this year as the impact of the U.S. slowdown spreads and soaring oil and food prices hurt spending.

Japan's government this week said the world's second- biggest economy is ``weakening'' for the first time since 2001. Gross domestic product in Japan probably shrank an annualized 2.3 percent in the three months ended June 30, according to a Bloomberg News survey.

.....

In China, economic growth slowed for a fourth straight quarter in the three months to June 30, expanding 10.1 percent. Growth below 9 percent would be ``unacceptable'' for a government targeting 10 million new jobs a year, Credit Suisse Group said this month.

South Korea's finance ministry on Aug. 7 said growth in Asia's fourth-largest economy is easing as consumer spending slows and higher fuel costs stoke inflation. An expansion of 4.8 percent last quarter was the weakest annual pace since the start of 2007.

While some of these growth rates are still strong, they are weakening. In other words, the PPP's arguments about "decoupling" (meaning the US can slowdown and the rest of the world can continue to grow at high rates) is bunk. But the problems aren't just in Asia:

Europe's economy will grow 1.2 percent next year, with growth in Germany, the largest of the 15 nations that share the currency, slowing to 1 percent from 2 percent this year, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Italy's economy unexpectedly shrank in the second quarter, edging it closer to a fourth recession in a decade as households and businesses struggle to cope with more expensive oil.

The economy, the fourth-largest in Europe, contracted 0.3 percent after expanding 0.5 percent in the first quarter, the Rome-based statistics office Istat said yesterday. Economists expected stagnation, according to the median of 22 forecasts in a Bloomberg News survey. From the same period a year earlier, the economy didn't grow at all.

Europe is also slowing down.

So -- two regions of the world that have been important US exports are now seeing lower growth. This will slow the rate of growth in US export sales, which in turn will hurt overall US GDP growth.

Now -- I haven't even mentioned the continuing problems in the credit market or the continuing fallout from the housing market which is still nowhere near a bottom. Neither of these two areas of the economy are helping growth. In fact, both are adding to the problems.

So, according to the NBER's far broader measure of economic activity we have the following facts:

1.) Personal incomes adjusted for inflation and not including the transfer payments are decreasing

2.) The year over year percentage change in job growth has been decreasing for several years, every time the year over year number has been at current levels over the last 50 years the economy has been in a recession, the unemployment rate has been increasing for a year and a half, and the number of people who are involuntarily working fewer hours are increasing.

3.) Industrial production has been decreasing for the last 9 months, capacity utilization is decreasing and several regional manufacturing indicators are at recessionary levels.

4.) Two important export markets -- Asia and Europe -- are experiencing slower growth. This will negatively impact US exports which have been one of the only bright spots over the last year or so.

5.) We haven't even discussed the continual deterioration in the financial or housing sector.

The conclusion is clear: we're in a recession and have been for a bit.