There wasn't any similar-sized stumble yesterday. But Catalyst Paper Corp., citing "adverse" market conditions, scrapped a $200 million offering of junk bonds the Canadian company planned to use for funding its business and other investments or acquisitions.

Meanwhile, underwriters delayed the launch of a buyout-financing deal for Myers Industries Inc. in the hope that the market would settle down in coming days. Late in the day, Magnum Coal Co. became the latest company to postpone a junk-bond offering, this one for $350 million.

In Europe, Arcelor Finance, the borrowing vehicle for Arcelor SA, which is being acquired by Mittal Steel Co., put off its plans to issue more than €1 billion ($1.34 billion) in bonds, citing the turbulent debt market. In Malaysia, shipping company MISC Bhd. put plans for a $750 million bond offering on the back burner.

In another sign that investors may be developing some indigestion from the buyout boom, Blackstone Group, the buyout firm that listed shares on the New York Stock Exchange last week, fell 2.7% in 4 p.m. composite trading yesterday to $29.92, below its offer price of $31 a share.

However, as another WSJ article notes, these events are not probably not fatal:

Part of the answer lies in the strength of the financial system's shock absorbers, which have improved since 1987, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 1998 Long-Term Capital mess and Sept. 11 attacks. Hedge fund Amaranth Advisors collapsed without many side effects. It looks like the same may go for the two Bear Stearns funds, whatever their fate.

Recent history is encouraging. The 1987 stock-market crash, as frightening as it was, didn't tank the U.S. economy. Neither did the horror of the Sept. 11 attacks. The economy gulped and then rebounded. That isn't any guarantee that the next crash or crisis, and there will be one someday, will have similarly passing effects on the impressively resilient U.S. economy. But it is encouraging.

Right now it appears market segments are at the beginning of a transition. As recent press reports indicate the super-easy credit terms of recent buy-outs are disappearing. Lenders and investors are demanding more loan covenants and in some cases higher interest rates. But lenders and investors don't appear to be asking for unreasonable terms. Instead, they appear to be asking for terms that would have been included in deals 5 or more years ago. In other words, borrowers have had it extremely easy over the last few years and will now have to pony up more conservative borrowing terms in their deals.

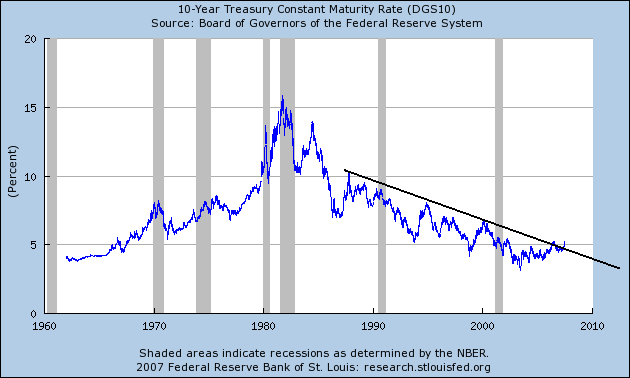

In addition, I have argued before that interest rates are far from restrictive. Here is a chart of the 10 year constantly maturing Treasury.

Interest rates have been higher during previous expansions and deals still got done and the economy still expanded at a strong rate. Over the last few years borrowers have gotten used to historically low interest rates. Right now borrowers have to contend with the fact that these days of incredibly easy money are over. But 5% interest rates are far from fatal.

BCA research makes a similar point although from a different analytical angle:

Increases in borrowing costs can typically be differentiated as reflective or restrictive. Reflective rises in yields are a product of vibrant growth. In order to keep investment and savings in balance, higher rates should accompany the increase in desired investment relative to desired savings. Eventually, a tipping point occurs in financial markets, at which point rises in bond yields hamper the economic expansion. While it is not easy to time this event, one variable to watch is the gap between GDP growth and interest rates. Based on this measure, it appears that interest rates are not yet restrictive. Consistently, share prices should perform well so long as rises in yields remain indicative of strong growth and an inflation scare does not develop. Bottom line: It will take a much sharper rise in the cost of debt to curtail the bull market in global equities. Until then, our outlook for higher stock prices remains intact.

Here they are arguing the increase in interest rates is simply the result of higher demand for funds. Considering the number of deals we have seen over the last few quarters, this makes sense. There is a ton of competition for funds right now, and borrowers are having to compete with each other to get lenders attention.

So short version, the Bear problems probably started a transition period in the debt markets. Super easy credit terms are over. But lenders and investors don't appear to be asking for unreasonable terms. My guess is this change will weed out some of the more questionable deals but allow the solid ideas to continue.

For the other side of this argument, see this article at the Big Picture. As always, Barry makes some very good points.