There is a diary currently up on the rec list at the G.O.S. where a commenter refers to my post yesterday pointing out that most of the economic data is actually still improving (BTW, LEI came out today at +.9), to which the author responded that "Bonddad did a good job going into the recession but his tendency to see the world as a bond trader gives him a blind spot," and another (quoting my conclusion) chimed in that Bonddad has "too much faith in charts and graphs."

As an initial matter, does NOONE read the goddam byline? I put it up there in italics for a reason - to emphasize that it is not Bonddad's post. But beyond that, riddle me this: when Bonddad was "doing such a good job going into the recession," and posting diaries chock full of graphs, among the 10,000s of comments to those diaries, WHEN DID EVEN ONE SINGLE PERSON COMPLAIN ABOUT THE USE OF GRAPHS? Feel free to educate me in the comments, but I was there. I participated in those threads. I can't recall even a single complaint lodged against Bonddad when the graphs he used pointed downward.

Nope. The complaints only came when those very same graphs started to point upward. Suddenly they became nothing more than "pretty pictures" which failed to take account of "fundamental analysis."

So, today is a good time to post a lengthy piece I drafted months ago, showing the pitfalls of "fundamental analysis" as practiced by a prominent former diarist at DK. I didn't publish it then becuase I didn't want it taken as a personal slam against that diarist, who was downsized out of an IT job, spent 99 weeks on unemployment, and is currently doing good deeds in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic. So, please do not interpret it so, I wish that diarist well. Nevertheless, read on for a demonstration of the problem of "fundamental analysis."

[Note: this part onward drafted in May 2011] Whether at political, economic, financial, or investing sources you will read reams of commentary about the economy, most of it extrapolating into the future, and almost everything you read in one seemingly intelligent article will be contradicted by the next just as seemingly intelligent article. Typically the author has an underlying ideology or Big Picture thesis, and presents opinion, authority, and/or data scoured from a variety of sources in support of that thesis.

And yet we know that following typical economic commentary gives you no more than a coin-flip's chance of being correct. Why not? There are some excellent reasons, including confirmation bias, where a writer or reader highlights only those facts supporting an already-held opinion and discounts or dismisses contrary facts. Furthermore, studies have shown that most commentators simply project existing trends into the future, and thereby miss turning points.

The following article, What will an economic recovery build upon?, appeared at the Huffington Post and several other sites on August 27, 2009. This is an article I have re-read probably a dozen times since it was published, better to understand what the author missed. I should note that as of last report the author was serving in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic. I applaud his endeavor and wish him well now and in the future.

I am republishing the article in full. All of the graphs are shown exactly as presented by that author (in blue), but updated through May 2011 (in red). As you read it, contemplate how compelling and persuasive case it appeared to make that a recovery simply could not have been starting based on the data it showed at the time. Based on this, the author stated at the time that the government stimulus would produce at most only two quarters of positive GDP.

Afterward, I'll comment on why you should treat even the most erudite, compelling "fundamental analysis" of the economy with bucketfuls of salt.

Now, without further adieu, here is the article:

================================================

There's been a lot of talk recently about the economy. Has it bottomed? Are we recovering? Will we see a "V" shaped bounce? Or a "U"? Or a "W"?

Since most of the economic numbers are still negative, it seems a little premature to talk about a recovery. Nevertheless, since the cheerleaders of the economy have brought it up, let's examine exactly what is going to lead this economy out of our deep recession.

In order to do that we must look at a topic that the Green Shoots crowd doesn't mention much -- the fundamentals of the economy.

I'm going to make this as simple and uncontroversial as possible.

Since consumer spending is more than 70% of the American economy, let's start there.

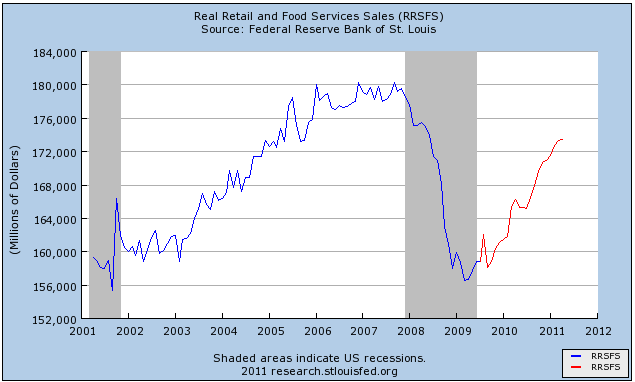

This chart shows us clearly why the economy has contracted so much. It also shows a clear bottom in consumer spending. The question is whether than bottom is temporary or permanent?

To answer that we must look at the fiscal health of the consumer. There are two measurements of that - money coming in and money going out.

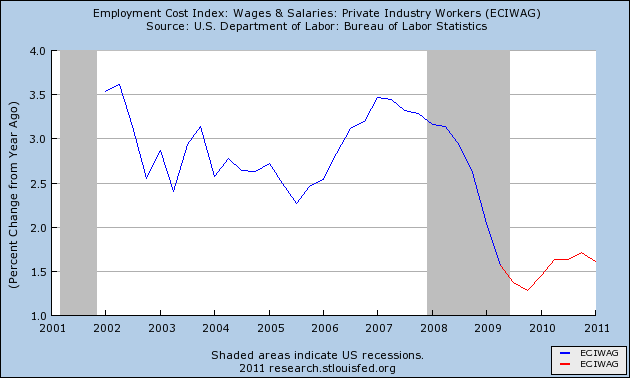

As you can see, workers have virtually stopped getting raises, and that assumes that people are still working.

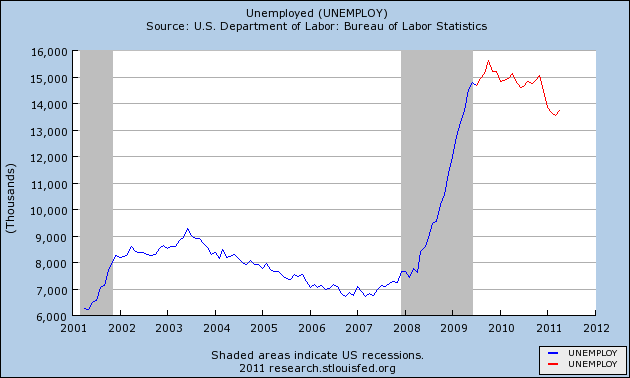

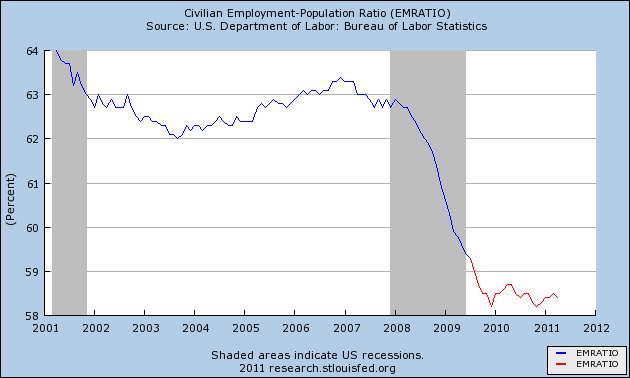

Obviously the American worker's income is under incredible pressure, and this is translating to less buying. The tiny downward correction on the number of unemployed in the chart above is due to nearly half a million workers no longer being counted as unemployed despite not getting new jobs.

There is another element to the American consumer's balance sheet, and that is savings and debt.

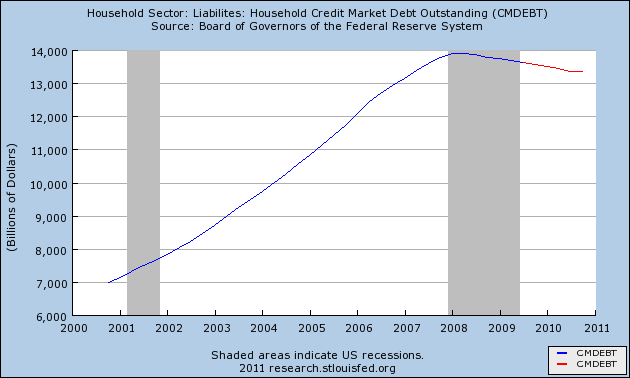

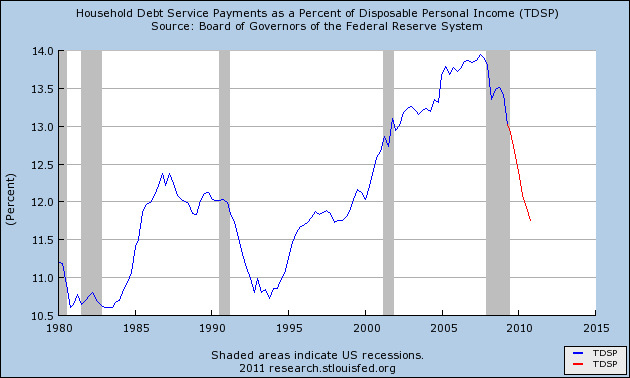

While there has been a modest improvement in the debt servicing levels of the American consumer, there has been very little improvement for overall debt levels. This is a reflection of lower interest rates, not to debt actually being paid down.

The debt charts are beginning to move the right way, but they are nowhere near close to what can be considered "healthy".

The San Francisco Federal Reserve put it this way:

The combination of higher debt and lower saving enabled personal consumption expenditures to grow faster than disposable income, providing a significant boost to U.S. economic growth over the period.

In the long-run, however, consumption cannot grow faster than income because there is an upper limit to how much debt households can service, based on their incomes. For many U.S. households, current debt levels appear too high, as evidenced by the sharp rise in delinquencies and foreclosures in r66ecent years. To achieve a sustainable level of debt relative to income, households may need to undergo a prolonged period of deleveraging, whereby debt is reduced and saving is increased.

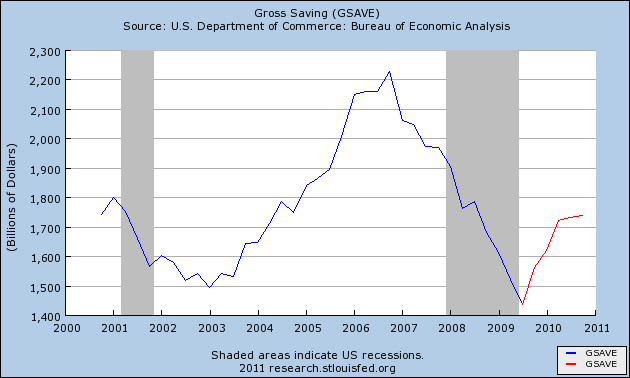

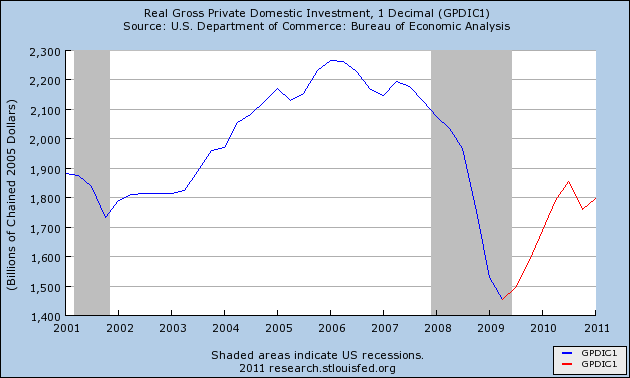

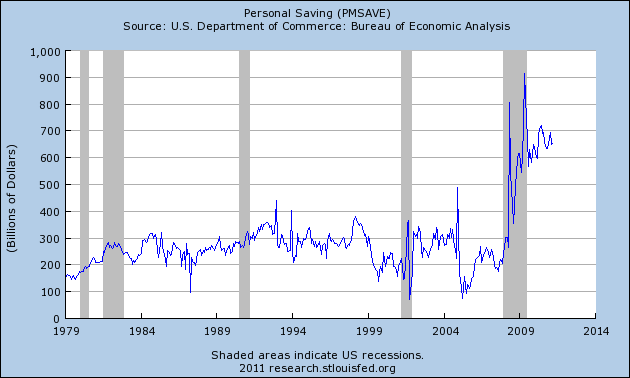

These two charts are the most damning of all. Without saving and investing there can be no sustained economic recovery. Period. This is an absolute disaster.

Not only do these charts show no bottom, they are moving in the wrong direction at a worsening rate. Until these charts reverse the fundamentals of the economy will get worse.

[NDD note: my emphasis]

The IMF summed up the situation this way:

Directors observed that the crisis will have important implications for the role of the United States in the global economy. The U.S. consumer is unlikely to play the role of global "buyer of last resort" -- suggesting that other regions will need to play an increased role in supporting global growth.Not all of the economy is domestic. America does get some economic support from foreign trade.

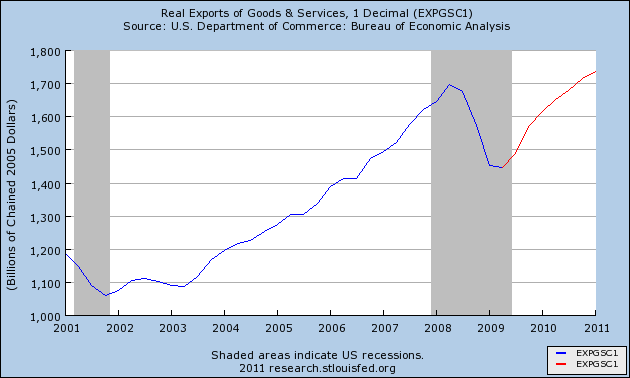

There are signs that the rest of the world is starting to recover, but to benefit from that America will have to produce products that the rest of the world wants to buy. So far there has been no significant signs that this is happening.

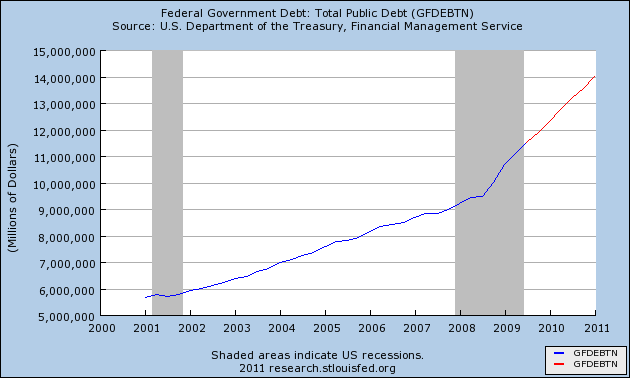

Of course there is one more element of the economy that I haven't covered here, and it is booming!

Lately there has been some improved housing numbers, but there are several caveats to them. For starters, the marginal improvement in comparisons are to the disastrous selling season of mid-2008.

Secondly, 43% of all home sales last quarter were first-time home buyers. Normally that would be a good thing, but this time it is a reflection of the government's $8,000 tax credit that people are rushing to take advantage of. Some people are even using it as a down payment.

In case people have already forgotten, borrowers that require extraordinary help getting into a house are much more likely to default on their mortgages. It looks like an attempt at reinflating the housing bubble.

Finally, those small signs of price increases are due entirely to more expensive homes being forced onto the market.

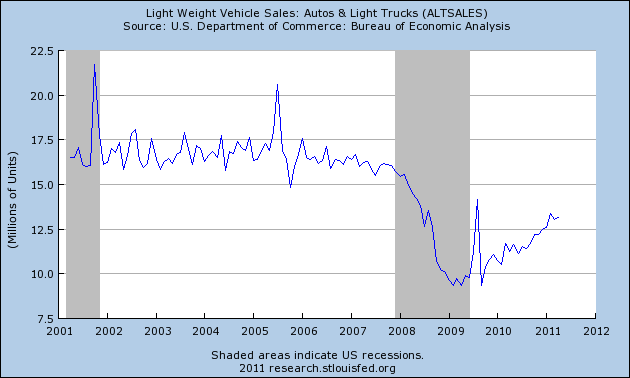

The other positive economic number we've seen recently is in auto sales. This is due to the recently ended cash-for-clunkers program.

So the spiraling government debt and the two most positive economic numbers are directly linked. With that in mind you have to ask yourself, what will the economic recovery build upon?

=============

The logic of the article seemed compelling, didn't it? And yet it turned out to be dead wrong. Let me make three points:

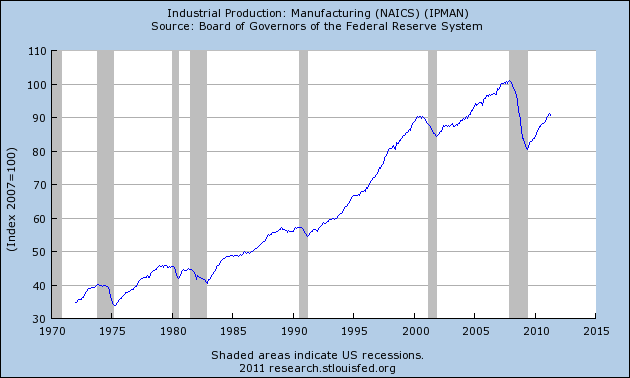

1. Hindsight is 20/20. Foresight beyond a few months is almost impossible. Looking back two years later, we know that more than anything else, manufacturing led the economy out of the bottom of the recession. [Update 8/19/11: and it is precisely because, in retrospect, we know that the recovery built on a boom in manufacturing and exports especially to Asia, that the downturn in manufacturing surveys is now so distressing]. Industrial production:

and the ISM manufacturing index have shown the steepest increases in several decades.

We also know that, because of ample personal savings built up during the recession

once conditions began to thaw, consumer spending did increase strongly as shown in the updated real retail sales graph at the beginning of the article above. And auto manufacturing increased by 4 million a year

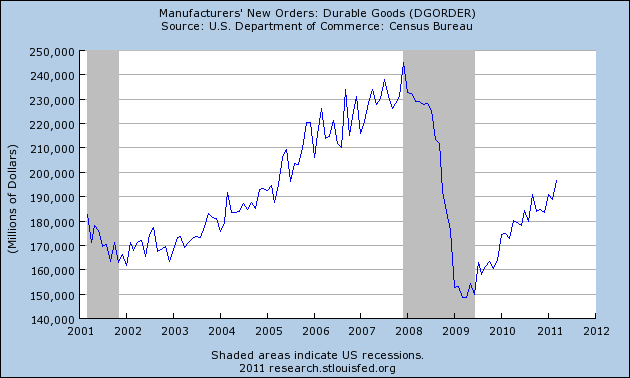

and durable goods purchases also increased strongly.

Just as in 1992 people could not foresee the impact that the internet would have, and how that would power a decade-long tech boom, and just as in 2001 people didn't know just how out of control the housing bubble, associated debt financing, and Wall Street leverage would become, so at the bottom of the great recession it was impossible to know that manufacturing would grow as strongly as it has, or that consumer debt refinancing would take place as quickly and strongly as it has.

2. Use of the present progressive tense is usually a sign of faulty analysis.

In the crucial highlighted paragraph, the author says that gross savings and investment "are moving in the wrong direction at a worsening rate," thereby assuming that the trend would continue. Of course it did not. It is almost always more proper to say a data series "has been moving" in direction X. Because, in fact, that is all you know. As I said at the outset, most economic observers just project past trends - usually based on data that is coincident or lags the general economy - into the future, and so they miss important turning points. In short, they get it wrong. As I pointed out at the time, one could have used the identical data series chosen by that author in 1982 or 1991 and they would have told the same pessimistic story - and have been just as wrong. Indeed, just as it was wrong two years ago to simply project the fearful declines into the future, so it would be equally wrong to simply project the upward trajectories of data recently into the future now.

3. While the past is never a perfect predictor of the future, what pundits miss is, economic cycles generally run in a typical order including both expansions and recessions, as demonstrated by Prof. Edward Leamer:

The temporal ordering of the spending weakness is: residential investment, consumer durables, consumer nondurables and consumer services before the recession, and then, once the recession officially commences, business spending on the short-lived assets, equipment and software, and, last, business spending on the long-lived assets, offices and factories. The ordering of the recovery is exactly the same.

No method is perfect, but if in the past eight economic cycles, A has led to B has led to C, then the odds are very good that in this cycle, if A has occured, B is going to occur and then C.

Studies of why pundits fail so often have been done, and time after time they have shown that most people simply project current trends forward. They fail to see the turning points and so are usually caught off-stride when the turn happens.

That is why I do not rely on intellectualized "fundamental analysis" as touted by the author of the very erudite article above. It is much better to dispassionately rely on data and take your personal biases out of analysis as much as possible.