Yesterday he wrote an article titled Not Yet Ready to Party where he expressed his concerns about future growth. His argument centers on the US consumer. Essentially, he is concerned that the percentage of growth attributable to consumer spending will decrease as a percentage of the US economy. He argues that the instead of accounting for approximately 71% of GDP growth, PCEs will revert to their historical median 65%. The decrease will be caused by a return to frugality -- consumers will simply stop spending in response to a poor labor market and to pay down their high level of current debt. As a result, GDP growth will be slow or non-existent.

My view is different. First, while I agree the consumer will be more frugal, I don't believe the frugality will lead to a decrease in consumer spending but a slower pace of consumer spending growth. This is due to a change in the way the consumer shops. Consider this exchange in the latest Barron's with a retail sales analyst:

What are some of the big trends you're seeing in retailing right now?

The consumer has definitely stabilized, and we have achieved this idea of a new normal. So consumers are still clipping coupons. They're still trading down to private labels. On the luxury side, fashion isn't selling as well. The consumer is willing to invest in something if she can use it for a long time. But if it is just fashion, it is only going to be in style for a season or two. Everyone faced a different kind of financial crisis in 2008. At the low end, the dollar stores have done very well. So your average household has probably shopped more at the dollar stores.

To me, the most interesting change has been the big move to eating at home. We were starting to see that trend in 2007 with higher gas prices. Then, when the recession hit, that accelerated significantly. So anyone who can sell food has seen a significant uptick in traffic, starting in 2008, although the amount spent hasn't necessarily responded because of the trade-down to private-label goods, where prices are cheaper. For a while, you were seeing an increase in sales of prepared foods. But once again, as the consumer really hunkered down, you saw a significant increase in the sales of scratch baking products. So consumers were buying food processors, pots and pans -- items they didn't have because they ate out so much. Consumers are spending where they see value, though different consumers define value differently.

How else have consumers' habits changed?

The consumer isn't thinking, "Do I spend it here or there?" Now it's, "Do I spend it or save it?" A lot of retailers are worried about the consumer's appetite for credit. People don't want to leverage up again, and they want to feel that they can manage within a budget. Some retailers are saying that the consumer isn't putting that extra item in the basket. And so even if it was a low-priced item, units per transaction are down.

I also believe this analysis (also from Barron's) of the coming consumer is correct:

AMERICA'S FLING WITH BLING MAY BE OVER, but the shift to thrift -- brought on by a sagging economy and stock market, and heralded on the cover of Time -- also has gone too far. According to Gallup, the polling organization, Americans cut their daily expenditures by more than 40% in the past year. That's not just fewer lattes; it's muscle and bone.

As savings rise and the market rallies, however, a new consumer is emerging, seeking a sensible middle ground between the gross excesses of the mid-2000s and the privations of the past year. He -- and more often, she -- is likely to find it in companies that offer great products, excellent service and outstanding value, which, by the way, doesn't always mean the lowest price.

As a result, I think consumer spending will contribute to growth but at a slower rate.

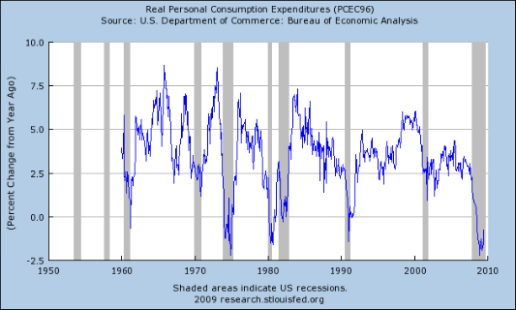

Regarding the actual pace of personal consumption expenditures, here is a chart of the year over year percentage change in real personal consumption expenditures:

Notice that during the most recent expansions there has been a sweet spot of year over year percentage change between 2.5% an 5%. Interestingly enough that number has never consistently been between 0% and 2.5% during an expansion. Yet there is nothing that says the year over year percentage change can't be at that level; it just never has.

Here is a chart of the quarter to quarter percentage change of personal consumption expenditures that goes back to 1990:

The median quarterly change in PCEs for this period was 3.2%. Notice how in the last two expansions the quarter to quarter PCE percentage change ranged from (in general) 2% to 4%. There is nothing indicating that rate of change couldn't be between 0% and 2%.

Therefore, while the consumer will not spend like he used to, the practical side of the equation means the consumer will eventually be forced to spend on items. This leads to the following conclusions:

1.) The consumer's situation (high levels of debt) and the economic situation (higher unemployment) will lead to lower consumption expenditures.

2.) The consumer will extend the life of most durable goods (cars and major appliances) by spending on parts and service. This will add to economic growth, but at a slower pace

3.) While the consumer will be spending less on items, when he does spend he will want more for his money. Instead of walking into a store, purchasing an item and leaving, the consumer will do more up-front research into items and want more service when he does purchase.

4.) The current drop in consumer spending is very much a by-product of low consumer confidence brought on by the worst recession of the last 60 years. As the economy emerges from this, consumer confidence will rise and spending will increase. However, spending will not increase to previous levels. Instead, we can expect the consumer to increase his personal consumption expenditures in the 0%-2% range of quarter to quarter growth.

The next question is where will the money come from. The first answer to that is that while income has been dropping, it appears to be stabilizing. Here is a chart of the last 6 months of total wages and salary disbursements.

Notice that over the last 4 months, this number as stabilized in a range between $6.441 billion and $6.213 billion. In other words, this number appears to the stabilizing. In addition,

Real disposable income has actually been increasing. A large reason for this increase is an increase in government transfer payments which in turn have gone to increased savings. However, the point is the money is available for increased consumption when consumer sentiment picks-up to a point where it can increase.

The above points come from an article I wrote titled the Fits and Starts Recovery where I outlined where I see growth coming from for the next 12-18 months.

Only time will tell who is right -- or if either of us is right. However, I welcome Invictus' insights and am pleased to have him aboard.