- by New Deal democrat

The most interesting results are the ones you don't expect to find, the ones that contradict your beliefs going in (Doomers really ought to give it a try sometime, as opposed to just searching for graphs that point down). Over the weekend, I decided to update my scattergraph comparing firing (via initial claims) vs. hiring (via nonfarm payrolls) to see if the relative weakness in job numbers compared with initial claims that started a year ago has persisted. The answer is, it has.

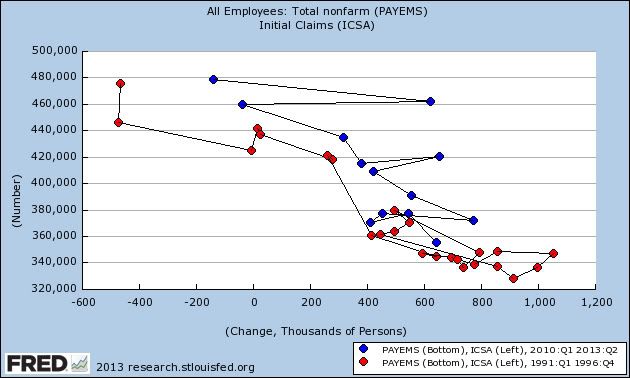

Here's the updated scatterplot graph. The monthly average of initial jobless claims is the left scale, the monthly nonfarm payrolls number is the bottom scale. This allows us to compare how much hiring we've been getting for any given level of firing during this recovery. The graph starts at the peak of initial claims in March 2009. Blue is the first three years, red is the last twelve months:

As you can see, the data points moved to the left and have remained there. That tells us that for any given level of firings, we've had less hiring in the last year. That was the result I expected.

But the surprise happened when I decided to compare the current recovery with the recoveries from the 3 previous recessions. I fully expected to find that for a given level of layoffs, there was more hiring in the previous recoveries, especially as layoffs declined under about 400,000. But that wasn't what I found at all.

The below scattergraphs compare the current recovery (blue), measured from the level when layoffs first declined to about 480,000 to the present monthly average of about 340,000, with each of the past three recoveries (red) during the period of time when layoffs were in the similarly declining 480,000 to 340,000 (or slightly less) range. Since the monthly data is noisy, there is a second graph for each recovery, totalled on a quarter to quarter rather than month to month basis, the better to show the comparison (Remember, for any given level of layoffs, left is weaker hiring, right is stronger hiring).

First, here is the comparison with 2000's economic expansion:

And here is the same data averaged quarterly:

Next, here is the 1990's tech boom:

Here is the tech boom compared quarterly:

Finally, here is the 1980's expansion:

Here is the 1980's expansion averaged quarterly:

Notice the startling results:

- For any given level of layoffs, hiring has consistently been better during the current recovery than during the economic expansion 10 years ago.

- In the current recovery hiring has also been equal to or better than hiring during the early part of the 1990's expansion. Only when layoffs declined to a level slightly below our current level did hiring really take off in the 1990's.

- Only during the first two years of the 1980's expansion was hiring for any given level of layoffs better than it has been during this recovery. After that the levels were about the same.

So why hasn't the current recovery generated more net jobs? Because it has taken so long for firings to decrease to a level consistent with strong hiring:

- In October 1982, initial jobless claims peaked at nearly 700,000. They were down to 333,000 27 months later.

- In March 1991, initial jobless claims peaked at just over 500,000. They were down to 313,000 21 months later.

- In September 2001 just after the terrorist attacks, initial jobless claims peaked at 517,000. They were under 400,000 only 9 months later, and were down to 335,000 43 months later.

By contrast, during the great recession initial jobless claims peaked at 670,000 in March 2009. It took 30 months before they declined to under 400,000, and they finally were down to 334,000 48 months later.

So the real story of the relatively poor payroll growth during this recovery hasn't been a dearth of hiring. Rather it has been the very long tail of elevated if slowly declining firing, that appears finally to have run its course.

UPDATE: And right on cue, Dean Baker alerts us to WaPo pundit Robert Samuelson, who writes Employers lack confidence, not skilled labor, claiming:

So, what explains more vacancies at given unemployment levels...? The answer almost certainly involves employers, not workers. Businesses have become more risk-averse. They’re more reluctant to hire.The nice thing about doing raw research and relying on hard data is that I can say beyond reasonable doubt that as to his wankery today, Robert Samuelson is a complete jackass.