- by New Deal democrat

Last weekend, Bill McBride a/k/a Calculated Risk wrote about "Predicting the Next Recession". As it happened, I had just finished writing a post that appeared Tuesday, "A note about the next recession"" which was markedly more pessimistic than Bill's view.

In this note, I want to explain where I disagree with Bill and the reasons why. The bullet point explanation is (1) I simply don't think we can reliably see that far ahead, so we shouldn't assume an optimistic outlook; (2) the odds of any expansion lasting 8 years as a general statement aren't good, and this one has been pretty weak for households; and (3) to the extent we can see murkily more than a year or so ahead, several adverse conditions are reasonably likely to occur.

I should begin by saying that CR and I have been generally on the same page for most of the last 5 years. The only other time I recall a specific disagreement was about the NBER dating the end of the last recession, and what would be required (CR thought new peaks in all the coincident metrics would be required to avoid a "double-dip." Citing past data, including from the Great Depression, I disagreed. In the end, the NBER did what I expected it to).

CR and I also see eye-to-eye about 2013, although I am more concerned about the impact of the 2% increase in tax withholding. Here's the summary conclusion for my 2013 forecast:

[T]he resurgeance of the housing market, and the continuing accomodation in interest rates and moentary policy, look like they will come to the rescue again later in the year, provided Washington can avoid burdening the consumer with further austerity measures taking effect this year.And here is CR:

I expect a pickup in growth over the next few years (2013 will be sluggish with all the austerity.In general, both of us agree that if Washington can avoid further weighing down the economy with immediate austerity measures, 2013 should see overall growth.

Where our views diverge is 18 months to 4 years out. Bill is optimistic, because he sees housing continuing to improve:

So right now I expect further growth for the next few years (all the austerity in 2013 concerns me, especially over the next couple of quarters as people adjust to higher payroll taxes, but I think we will avoid contraction). I think the most likely cause of the next recession will be Fed tightening to combat inflation sometime in the future - and residential investment (housing starts, new home sales) will probably turn down well in advance of the recession. In other words, I expect the next recession to be a more normal economic downturn - and I don't expect a recession for a few years.I think it is more likely that a new recession will begin before Obama's second term ends, and will start out from an already depressed state, much like 1938:

in my opinion the odds are not very good that this recovery, which is already going on 4 years old, is going to last 3 more years or longer. It's close to the weakest recovery on record in terms of restoring us to the prior peaks of employment and personal income and wealth. The cold, hard, fact is that at some point in the next few months, or in a year or two, or in any event almost certainly at some point in Obama's second term, we are going to have the next recession.CR and I agree that most pundits miss turning points, either because they are incentivized to do so (bullish Wall Street forecasters, Pied Pipers of Doom on the internet), or because they tend to simply project existing trends into the future. The use of long and short leading indicators to instruct our opinions helps avoid that pitfall. But that also means that we should not project that long leading indicators will continue their current trend -- i.e., they don't predict themselves.

Yet a lynchpin of CR's analysis appears to be a tacit assumption that housing booms and busts tend to be long cycle events, and that long term interest rates will not increase. He refers us to a prior piece where he said growth will be due to:

a combination of growth in the key housing sector, a significant amount of household deleveraging behind us, the end of the drag from state and local government layoffs, ... some loosening of household credit, and the Fed staying accommodative....My differences with CR's argument are two. First of all, since housing itself is a long leading sector, I have very little idea what housing starts and permits will show 3, 6, 12, or 24 months from now. They may be up or down. Thus our ability to use them to forecast the economy out past about 12 to 18 months almost completely fades away.

Secondly, to the extent we can see beyond 12 to 18 months, the Fed remaining accomodative is not enough. Either real household income most increase, or the ability or willingness to refinance existing debt or take on new debt must increase - i.e., inerest rates cannot simply remain stable, they must actually decrease. This leads me to discuss two data series that actually do seem to lead housing: long term interest rates and the real personal savings rate.

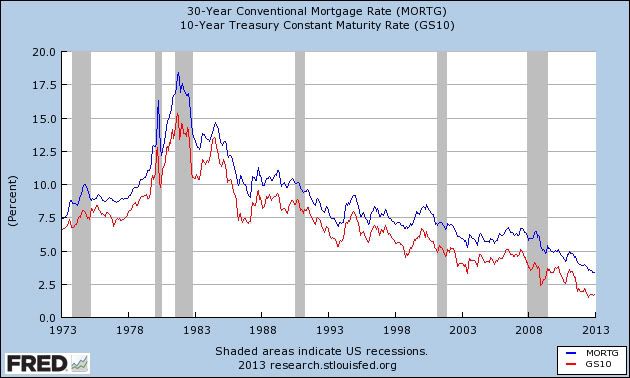

Let's first look at long term interest rates. Here is the 10 year treasury bond vs. 30 year conventional mortgage rate since 1983:

Note that they almost always move in tandem.

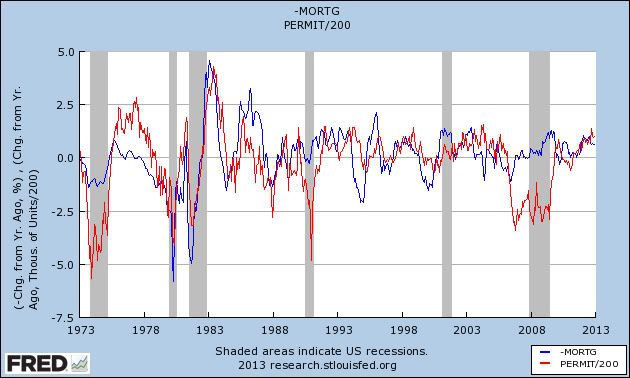

Now here is a comparison over the last 40 years of the YoY change in mortgage rates (inverted so a higher mortgage rates means the line is lower)(blue) vs. housing permits (red):

Note that the blue line leads the red line by a short time, i.e., the YoY change in mortgage rates is almost always reflected by a move in the same direction by housing permits some months later.

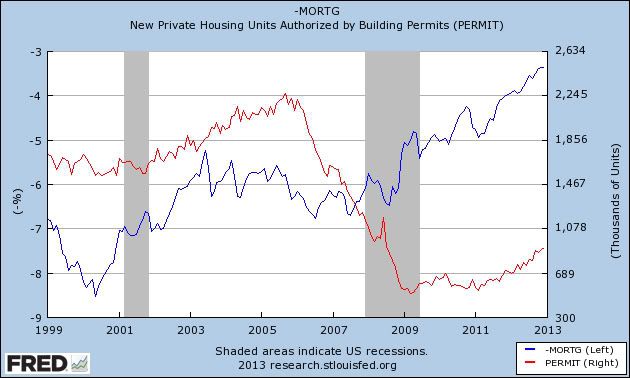

The use of a YoY measure automatically cuts down on the leading relationship. When we measure the actual mortgage rates (blue, inverted) and compare them with permits (red), we see that the leading period tends to be several years:

At the moment, mortgage rates are slightly out of phase with long term treasuries, which have not made a new bottom for 6 months. One or the other should move back in tandem shortly.

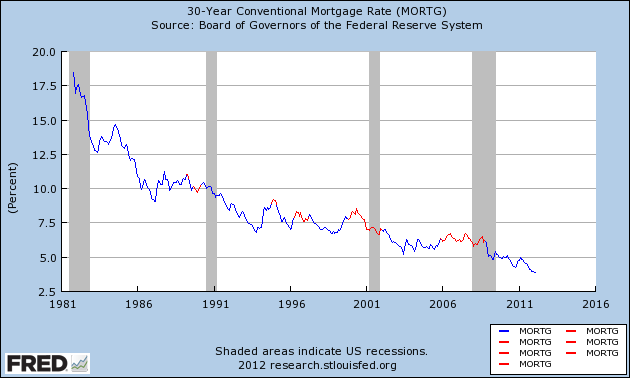

Most important of all for this analysis, since 1983, a recession has always been preceded by a 3 year period when long term interest rates have not established a new low:

At some point, interest rates really can't move much lower. And since interest rates tend to move in very long, ~60 year cycles, and we've had a down cycle for just over 30 years, a secular, long-term shift towards increasing interest rates is very likely. In summary, (1) mortgage rates tend to lead housing permits and starts, and (2) it is more likely that over the next 3 years mortgage rates will rise, or at very least not decline significantly further from here.

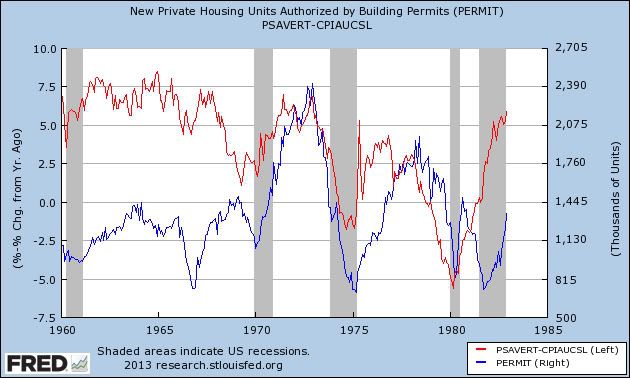

Now let's look at the second data series which has a tendency to lead housing permits and starts, albeit noisily: the real personal savings rate. In my 2013 forecast, I noted that the signal from the real personal savings rate (the savings rate minus inflation), which generally measures household optimism or pessimism about spending, was more ambiguous than other long leading indicators, and actually was consistent with a slight contraction early this year. Let's go further, and let me show you a comparison of the real personal savings rate (red) with housing permits (blue) for the last 50 years. First, here' s the period from 1963 to 1983:

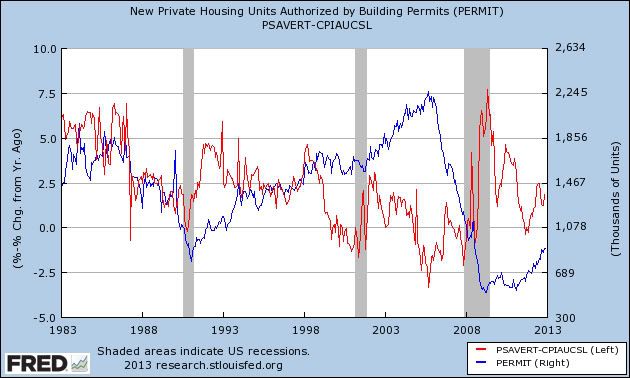

and here is 1983 to the present:

Note that the real personal savings rate tends to peak well ahead of housing permits (1965 vs. 1969, 1971 vs, 1973, 1975 vs. 1978, 1993 vs. 1998, 2002 vs. 2005, the two exceptions being 1980 and 1984 vs. 1982). The same pattern is true, and usually closer in time, for troughs (1969 vs. 1970, 1974 vs. 1975, early in 1980 vs. later 1980, early in 1991 vs. later in 1991, and 2006 vs. 2011, the exception being 2001 vs. 2000).

The real personal savings rate made a post recession peak in 2009, and at least an interim trough at the end of 2011. This tells us that the increase in housing permits might not last that much longer, although whether it is this year or a year or two from now is impossible to know. With wage increases only averaging 1.5% a year, it seems that households are likely to become more stingy, rather than more carefree, about spending, and thus more likely that the real personal savings rate will increase rather than decrease from here.

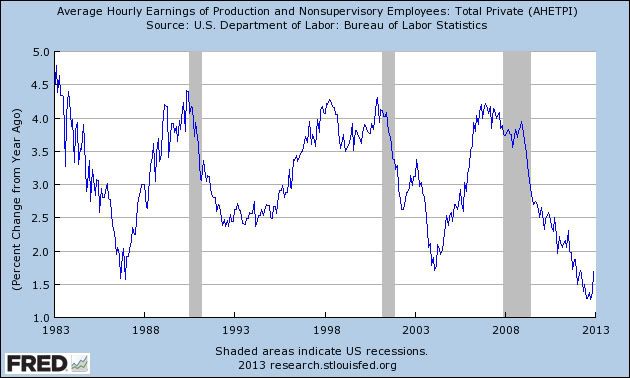

Now let me make a few concluding comments. CR's analysis has several important points in its favor. First of all, with 30 year mortgage rates just having made new lows, and 10 year treasuries having made new lows 6 months ago, that suggests expansion could go on another 2 1/2 to 3 years. If households do not retrench their spending, and the real personal savings rate either decreases or at least does not increase, that too will allow further expansion. finally, if real household incomes actually increase over the next few years, this would allow the expansion to continue. Note that YoY wages just had a sharp increase in the last month:

In the past several expansions, there were positive sharp reversals in 1986 and 2004. I would like that to be the case now, but unfortunately I suspect it is simply noise.

I remain more pessimistic about the longer term. To reiterate, beyond about 12 to 18 months out, we really can only surmise the most murky outlines of the economy. That being said, unlike CR, I am not at all confident that housing permits will continue to increase over the next several years. A move to near 3% or even higher in long term interest rates for a sufficient period of months - or even a mild increase for a sustained enough period of time - would be enough to halt the advance of the housing market; as will any sustained move by households to increase their savings rate. Since I view one or both of these as reasonably likely events, that would cause a top to form in housing permits, and then the long leading indicators will start to forecast deterioration in sufficient time to bring on a recession at some point in Obama's second term -- and, I repeat, a recession that will probably start with depressed levels of unemployment, household income, and wage growth.