Jeff Rubin, a former CIBC chief economist and author of a book on oil and globalisation, told the FT: “Triple-digit oil prices are going to threaten a world recovery.”My co-blogger Bonddad said much the same thing last week:

If there is one thing that could really kill the expansion quickly, it's oil prices.So let's take another look. Let me start by just repeating what I said back in January:

if consumers once again have to pay over $3 a gallon for gas (which ~$90 Oil would give us), it will have a psychological as well as economic impact on consumers, and I would expect them to cut back in other areas. This looks likely to be the case. We are just 6 months into renewed economic expansion, and at the seasonal low for Oil prices, and already Oil is at $80 a barrel. It is a near certainty that the expansion will continue for at least 3-6 more months. Does anyone see any reason for Oil prices to decline in that period? Of course it could happen, but it doesn't seem likely. It seems much more likely that Oil prices will continue to increase, but slowly this time as opposed to the skyrocketing speculative blowoff that led to $147 Oil in July 2008.

Whether $90+ Oil will lead to a full-blown double-dip economic contraction, or just a slowdown later in the year, is almost impossible to gauge. It depends upon how far over $90 Oil shoots, and how long it stays there. If there is a dramatic overshooting a la 2007, there will be a double-dip. If there is a gradual increase over $90 that does not last that long before consumers cut back and the feedback loop causes price declines, then there may just be a slowdown, or if there is a contraction, it may be shallow and only last a quarter or two -- which is my best guess, and only a guess, at this point.

[W]hen energy prices go up, consumer spending falls. But there are two surprising things about the quantitative character of this response. The first surprise is the delay-- energy prices go up at time t, but the biggest consequences for consumption spending aren't seen until [ ] 12 months later. The second surprising feature of these results is the magnitude. If consumers continued to purchase the same number of gallons of gasoline as they had before, a shock of the size analyzed in this graph would require them to reduce spending on other items by 1%. Yet eventually they historically would be predicted to reduce spending by 2.2%. ... [C]onsumers cut spending by [ ] much more than the shock itself."

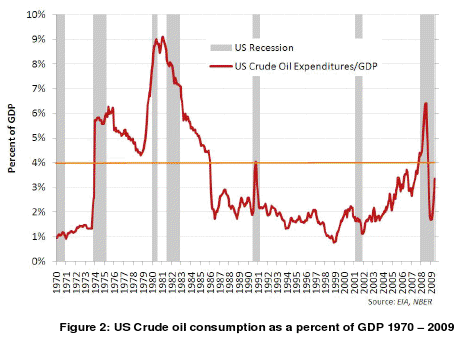

The US has experienced six recessions since 1972. At least five of these were associated with oil prices. In every case, when oil consumption in the US reached 4% percent of GDP, the U.S. went into recession. Right now, 4% of GDP is US$80 a barrel oil. So my current view is that if the oil price exceeds US$80, then expect the U.S. to fall back into recession.

What do these estimates imply looking forward, with oil prices now back up to $80 a barrel? The relation used to produce the figure above assumes that there is a threshold effect before the next oil price shock would begin to do its damage. According to that relation, oil has to get back above $130 before it would matter again for GDP growth. On the other hand, the original research on which that relation is based acknowledged that there's really not a very compelling basis in the data for choosing among various plausible nonlinear possibilities. The other approaches surveyed in my Brookings study assume a simple linear relation, according to which the recent resurgence in oil prices would already begin to exert a drag on spending.Another magnitude that I think is important to watch is the share of the budget of an average U.S. consumer that is devoted to energy purchases. This had fallen considerably in the 1990s, making it easier for many consumers to largely ignore modest energy price fluctuations. When this share rises above 6%, it seems to become a more significant factor. The consumer energy expenditure share peaked last summer at 6.8%, but collapsing energy prices subsequently brought it back down to 4.7%. The resurgence in oil prices this summer had pushed that share back up to 5.4% in September [as shown on the graph below:].

[N.B.: Kopits measures Oil prices as a percent of GDP. Hamilton measures Oil consumption as a percent of consumer spending. Since consumer spending is about 2/3 of GDP, Kopits' 4% figure and Hamilton's 6% figure are virtually identical.]

A most interesting corrolary was brought up by Spencer of the Angry Bear blog in the comments:

If you do consumer spending on energy as a share of consumer spending plus spending on autos you get a very stable ratio. This suggest one of the biggest ways consumers adjust to higher oil prices is to delay buying a new auto.

Kopits said that $80 Oil would derail the recovery. Hamilton suggested it would take $130. Where do we stand now?

Let's look now at the price of Oil. This is a graph of Oil prices per barrel for the last 12 months (up to one week ago):

Note that the price of Oil doubled from its low of about $35 a barrel at the beginning of 2009, to over $70 a barrel by June. That's a 100% increase, and according to Kopits, should have put us back into recession. Obviously, it hasn't worked out that way. According to Prof. Hamilton's work, we are right now in the period ~12 months after the major increase of early 2009, and so are at the time of its maximum impact. Since both the LEI and GDP are still increasing, that spike has not derailed the recovery. A price spike from a very low percentage of GDP to a rate that is still under 4% of GDP does not appear to create a recession. Crossing the 4% threshold looks like the decisive determinant.

Note secondly that the price of Oil has climbed gradually since last June at a rate that is less than 50% a year. Oil hit $75 last June and is presently about 15% higher. So in the second half of this year, i.e. 12 months after this gradual increase, there is no "shock" that consumers would be reacting to.

That brings us back to Prof. Hamilton's update yesterday. While again I encourage you to read his entire piece (and his two prior pieces, they are treasure troves of information), here is the summary:

With gas prices now about a dollar per gallon higher than they were a year ago, that leaves consumers with $12 billion less to spend each month on other things than they had in January of 2009. On the other hand, the U.S. average gas price is still more than a dollar below its peak in July of 2008. Changes of this size can certainly provide a measurable drag or boost to consumer spending, but are not enough by themselves to cause a recession.[I]t is not just the level of consumer spending but also a sudden change in its composition that sometimes contributes to an economic recession. When oil price increases are sufficiently sudden and dramatic, we see abrupt drops in consumer sentiment, postponement of purchases of consumer durables, and important changes in the kinds of vehicles consumers buy. Because labor and capital can not costlessly shift out of the affected industries, the result is unemployment in those sectors which is an important additional factor bringing the economy down.

....

[W]ith retail gasoline prices still a dollar a gallon below what consumers have recently seen, I'm doubtful that gasoline prices have the ability to induce as much consumer anxiety as we observed two years ago. Although recent increases in prices have brought energy expenditures back up as a share of total consumer spending, they're still below the 6% level at which consumers historically have started to make dramatic adjustments.

Prof. Hamilton's analysis looks correct to me at this point. Remember that, in his analysis, Oil price increases first show up as increased spending, or decreased savings, and indeed the personal saving rate has declined again in the last few months:

And the Oil consumption statistics of the Department of Energy show that the increase in energy consumption YoY that took place in 2009 has virtually stopped. Since the beginning of this year, consumption has generally been no more than equal to that of last year.

The same indication of constricting demand has shown up in YoY miles driven, which turned negative in January as indicated in this graph:

But retail sales, and in particular Spencer's metric of new auto sales, have not declined at all and if anything continue to look like they are increasing:

In summary and conclusion, it appears that in order to trigger a recession, there must be a large price spike that swiftly causes Oil consumption to be 4% or more of GDP. On the other hand, a very gradual price move, such as we have had since last June, causes consumers to alter their behavior in a way that results not in a recession, but enough of a slowdown in growth that Oil consumption declines and Oil prices follow, having never risen higher than 4% of GDP. That's what is suggested by Oil futures prices at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which remain in "contango" (i.e., prices rising as we go further out into the future), but do not reach $90 until the December 2011 contract, and the 2018 contract sells for $95.08. This suggests to me that the futures market believes that higher prices now would not be sustainable.

There are other forces in the economy pushing it towards another deflationary bust in the future, chief among them downward pressure on wages, which rose at the rate of about 1% a year when last measured. House prices look to begin to decline again. And the Atlanta Fed notes that

the moderation in price changes was widespread across many categories of spending [last year]. This moderation was evident in the appreciable slowing of inflation measures such as trimmed means and medians, which exclude the most extreme price movements in each period.... {So] It's not just the housing sector that is driving the recent disinflation trend.Nevertheless, if those other factors do not push the system back into outright deflation, barring a spike in the price of Oil prices, as of now it appears more likely that the economy will slow down its growth later this year enough to cause a gradual decline in Oil prices with renewed economic growth.