The U.S. economy's take-off from a near standstill in the first quarter may prove bumpier than the Federal Reserve and many on Wall Street expect as tighter credit acts as a headwind to growth.

What started as a financing squeeze in the subprime- mortgage market now threatens other parts of the economy. Borrowing costs for companies are climbing as banks and investors demand more for their money. Consumers feel the pinch from rising interest rates and sagging house prices.

As a result, the economy may struggle to achieve the 2-1/2 to 3 percent growth rate that most forecasters inside and outside the Fed have penciled in for the second half of the year. Instead, economists at International Strategy & Investment Group, UBS AG and Commerzbank AG see growth below 2 percent as consumer spending slows and business investment fails to pick up under the weight of tougher financing conditions.

As I've written before, I am having a hard time buying the "interest rates are at a restrictive level" argument.

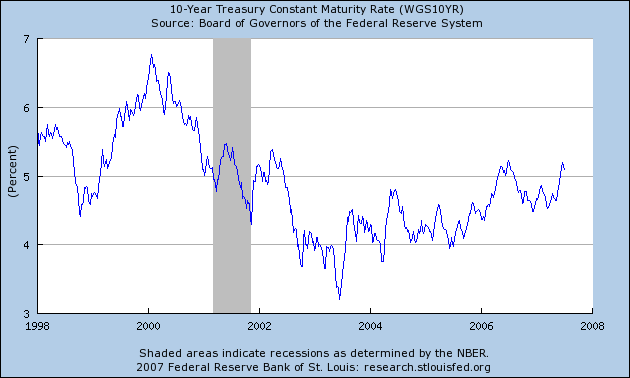

Here's the 10-year CMT Treasury chart:

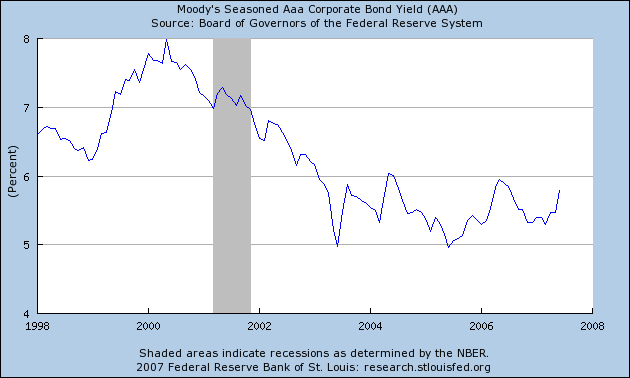

Here's the Moody's seasoned AAA chart:

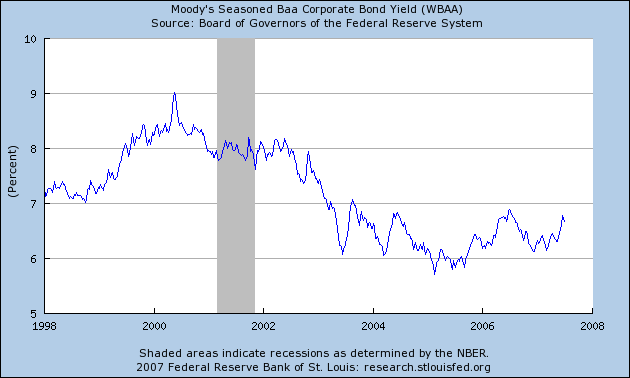

Here's the Moody's seasoned Baa chart:

None of these interest rate levels look restrictive, especially compared with levels at the end of the 1990s.

Investors now demand almost 3 percentage points in extra interest to own U.S. high-yield bonds rather than government debt, compared with a record low of 2.41 percentage points on June 5, Merrill Lynch & Co. data show. That's the fastest increase in spreads since April 2005.

``The credit cycle is peaking,'' says John Lonski, chief economist at ratings company Moody's Investors Service in New York. He sees the high-yield spread rising to 4 percentage points by the end of 2007.

The tougher corporate-credit conditions are starting to bite. In the past two weeks, more than a dozen companies postponed or restructured debt sales.

Among those postponed: a $350 million note sale by Magnum Coal Co., a West Virginia-based coal producer, and a $500 million bond sale by Kia Motors Corp., South Korea's second largest automaker. Kia planned to use some of the money to help finance construction of a U.S. factory employing 2,500 in Georgia.

3% above Treasuries is about 8%. That's still not that high. One of the main issues in the LBO market is borrowers have gotten away with incredibly lax lending standards. For example, some recent LBOs have had a covenant that if a borrower couldn't make a payment, he could instead issue more bonds (I forget the technical term for this practice). Why any lender would accept this term is simply beyond me. A borrower who can't pay now probably won't be able to pay in the future. Yet lenders accepted these terms as they chased yields.

It's also important to note that companies have a ton of cash on their books right now. According to the Federal Reserve's Flow of Funds Statement (PDF) nonfarm nonfinancial corporate business has $2.683 trillion of collected financial assets (see pages 103 and 104 of the FOF report). In short, the money is out there to get deals done.

My guess is the market will now return to more prudent lending and borrowing standards. That does mean some of the more aggressive terms will no longer be included in these deals. However, good deals will still get done.