As I have written extensively in the last several months, a rise in interest rates has almost always - 17 of 21 cases since World War 2, to be precise - been consistent with an outright decline several quarters later in housing. Typically a 1% increase in interest rates has been consistent with a 100,000 decline in the volume of housing permits and starts.

But what about the 4 exceptions? Are they just random outliers, or is there a common thread linking them?

It turns out that, in at least 3 of the 4 cases, there is a common thread: in the immortal words of housing bubbleheads circa 2005, "Buy now or be forever priced out."

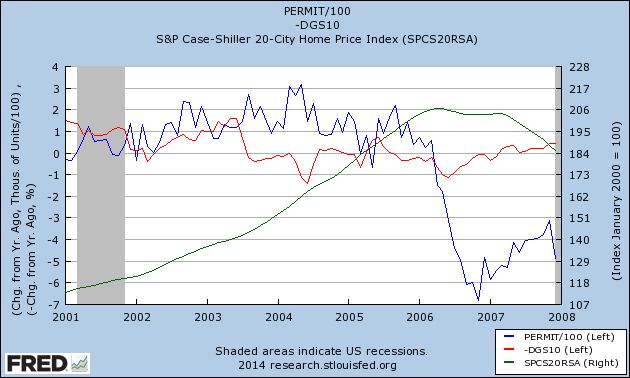

The housing bubble of 2004-06 remains the biggest exception in the nearly 70 year history of housing and interest rates that I've examined. Here's the graph of interest rates YoY change (inverted, red) and housing permits YoY change (blue) during that period and the immediate aftermath:

As you can see, despite the fact that interest rates not only had not fallen, but in fact had risen somewhat and remained elevated for several years, housing permits continued to increase stoutly. As we all recall that housing prices (Case Shiller Index, green, index values at right) were rising at the brisk clip of 10% or more a year for about half a decade at that point. It was a common trope that "real estate only goes up!" If so, you had better buy today, because tomorrow the house you wanted would only get even more expensive. And for a long while it did. Until it didn't, and housing crashed in equally spectacular fashion, as you can see from the latter part of the graph above.

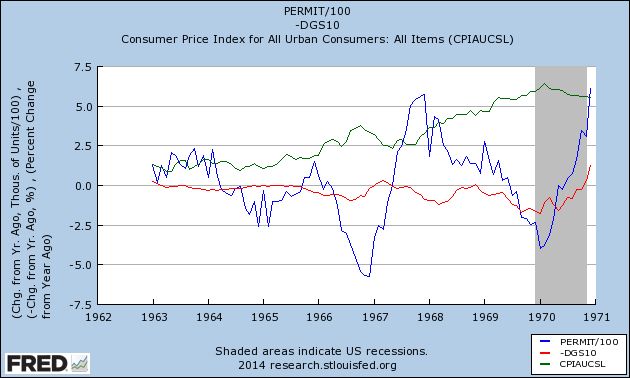

A similar, although not identical, explanation can be found to the exceptional performance of housing in 1968, and to some extent, also in 1979.

Inflation and interest rates had remained tame throughout the 1950s, and slightly increased in the early 1960's.

But in 1965, Lyndon Johnson began his "guns and butter" fiscal policy. Previously, it had been understood that you could only either finance wars (guns) or domestic programs (butter). Johnson believed the US was so strong that he could do both. The result wasn't just inflation, but increasing levels of inflation every year beginning in 1965. By 1968, inflation had increased to 4% and showed every sign of accelerating further (and indeed it did). In its report for 1968, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis pointed out this increasing rate of inflation with alarm. It appeared to be the number one economic issue facing the country.

This meant an aspiring homeowner had to deal with not only an increased mortgage rate (which would ordinarily drive housing construction down), but the belief that, if s/he didn't buy a house now, then in 3 or 6 or 12 months those mortgage rates would be even higher. Needless to say, the prudent buyer bought now rather than later, despite the higher interest rates.

And that's what the graph shows (green line is YoY inflation rate):

Notice that these sales only borrowed from future demand, as at the end of 1969 the US entered its first recession in almost 10 years.

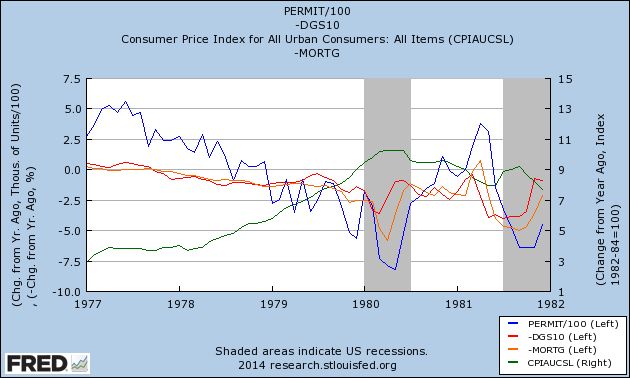

The same dynamic was in play in 1978, with the same result. Here's the graph:

Additionally, in 1978, there were several months that mortgage interest rates (orange) declined significantly, and were in fact negative YoY. This coincided with spikes in housing. Contrarily, there were several months in 1978 that were negative YoY, although not negative enough to result in a negative YoY quarter. Nevertheless, the reckoning was only delayed until 1979.

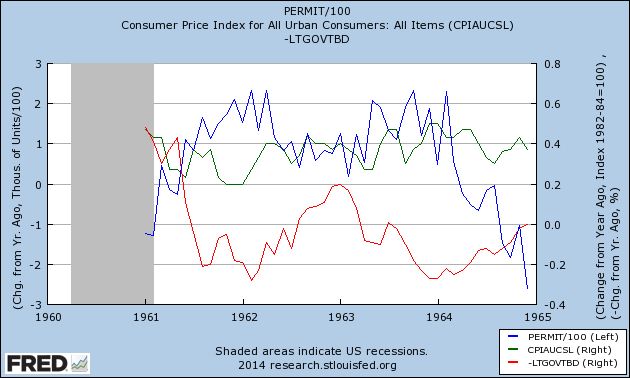

That leaves only 1962. I have been unable to find any reliable source of what may have happened with mortgage interest rates that year. We can say that the increase in interest rates was relatively short-lived, and that while housing never turned negative, it did turn lower for about a year, falling under +50,000 for 3 of those months. You can also see that inflation (green) began to tick up at this point:

In short, the exception to the rule that rising interest rates are associated with a decline in housing about 6 to 12 months later is when the costs of buying a house not only have risen, but it is expected that they will rise even further in the immediate future. In those circumstances, it makes sense not to delay the purchase of a new house even though interest rates have already moved against you.

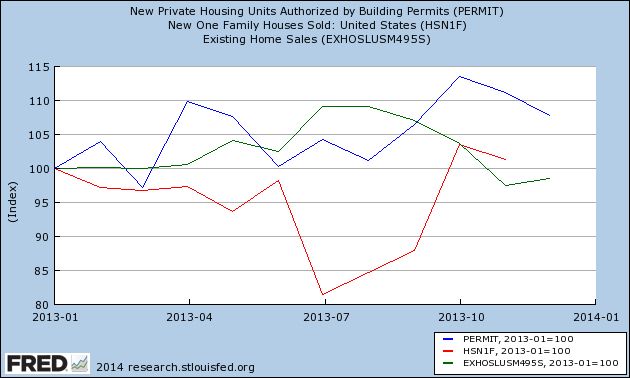

So, is there a component of "buy now or be forever priced out" in the present environment? Actually, I believe there has been, evident in the spikes of demand in July and August in existing home sales, and in October and November in housing starts and permits, as shown in this graph of housing permits (blue), new home sales (red), and existing home sales (green) since January 2013:

A number of buyers may have tried to lock in rates before they rose any further, as evidenced by the surge in existing home sales in July and August, and permits and new home sales in October and November. That dynamic appears to be fading, and there does not appear to be any mentality that mortgage rates will continue to rise significantly from here. If anything, interest rates seem likely to meander around their current level, and buyers will take advantage of the dips. But that is not the same as "buy now or be forever priced out."

The bottom line is that the exception to the rule that rising interest rates cause a decline in the housing market does not appear to be in play at present. So, having considered the exceptions to the rule, I continue to believe that housing will actually experience a decline (that has already begun) in approximately the first 6 months of 2014.