U.S. consumer spending was flat in February after adjusting for inflation, the third consecutive month of weak consumer demand, the Commerce Department reported Friday.

Real consumer spending has risen less than 0.1% seasonally adjusted since November, a clear sign that the main engine of U.S. economic growth is stalling as job growth wanes and house prices tumble.

Real consumer spending is on track to rise 0.8% annualized for the first quarter, economists said. "The plunging confidence numbers clearly point to an outright decline in the second quarter," wrote Ian Shepherdson, chief U.S. economist for High Frequency Economics.

"I would say that while to date the problem banks have been quite low, there clearly has been some deterioration since the beginning of this year, and should the economy continue to slow down, as many expect, it is likely that we will continue to see some growth in the problem institutions," he told a seminar at the Bank of Korea.

.....

Rosengren said the turbulence was difficult to foresee because bank models focused solely on their exposure to riskier assets like subprime mortgages, ignoring the possible knock-on effects on other sectors.

"What these stress tests crucially failed to capture was the effect of house price declines on the large holdings of highly rated securities that global banks held -- the products of mortgage securitization activities, with their payment streams ultimately tied to the performance of subprime loans," he said.

The belief that housing prices would never fall on a national basis, which permeated even the Fed itself, was partly to blame for this underestimation of risk, Rosengren said.

Federal bank regulators plan to increase staffing 60 percent in coming months to handle an anticipated surge in troubled financial institutions.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. wants to add 140 workers to bring staff levels to 360 workers in the division that handles bank failures, John Bovenzi, the agency's chief operating officer, said Tuesday.

"We want to make sure that we're prepared," Bovenzi said, adding that most of the hires will be temporary and based in Dallas.

There have been five bank failures since February 2007 following an uneventful more than two-year stretch. The last time the agency was hit hard with failures was during the 1990-1991 recession, when 502 banks failed in three years.

The FDIC provides insurance for deposits up to $100,000. While depositors typically have quick access to their bank accounts on the next business day after a bank closure, winding down a failed bank's operations can take years to finish. That process can include selling off real estate, investments and dealing with lawsuits.

There are 76 banks on the FDIC's "problem institutions" list — which would equate to about 10 expected bank failures this year, though FDIC officials declined to make projections. Historically, about six banks fail per year on average, FDIC officials said.

Since 1981, total failures per year averaged about 13 percent of the number of institutions that started the year on the agency's list of banks with weak financial conditions.

There have been two failures in 2008 — both of which were small Missouri-based banks. By far the largest recent failure was the September 2007 shutdown of Georgia-based NetBank Inc., an online bank with $2.5 billion in assets. NetBank's insured deposits — representing more than 100,000 customers — were assumed by ING Bank, part of Dutch financial giant ING Groep NV.

Federal Reserve officials may be rethinking their aversion to acting against asset-price bubbles, an article of faith during former Chairman Alan Greenspan's 18 years at the helm.

After this month's near-collapse of Bear Stearns Cos., Minneapolis Fed Bank President Gary Stern -- the longest-serving policy maker -- said in a speech yesterday that it's possible ``to build support'' for practices ``designed to prevent excesses.'' New York Fed President Timothy Geithner, whose district bank took on almost $30 billion of Bear Stearns assets to rescue the firm, argued two years ago for a larger role for asset prices in decision-making, and there's no indication his views have changed.

For Fed policy makers, ``the consequences of their permissiveness have become so disastrous that they simply can't keep singing the same old tune in public,'' said Tom Schlesinger, executive director at the Financial Markets Center in Howardsville, Virginia.

While the soul-searching is unlikely to result in immediate changes to monetary policy, Stern's comments show how the credit freeze has forced officials to scrutinize long-held philosophies about the Fed's role in markets, and even ask how their current policies may undercut those views.

``As a risk manager, the Fed needs to take account of both directions, not just dealing with the aftermath,'' said Bruce Kasman, chief economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York. ``We have had two asset-prices bubbles in the last 10 years that have had big implications for the Fed's desire for a more stable macroeconomy.''

First, the Federal Reserve Board voted unanimously to authorize the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to create a lending facility to improve the ability of primary dealers to provide financing to participants in securitization markets. This facility will be available for business on Monday, March 17. It will be in place for at least six months and may be extended as conditions warrant. Credit extended to primary dealers under this facility may be collateralized by a broad range of investment-grade debt securities. The interest rate charged on such credit will be the same as the primary credit rate, or discount rate, at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

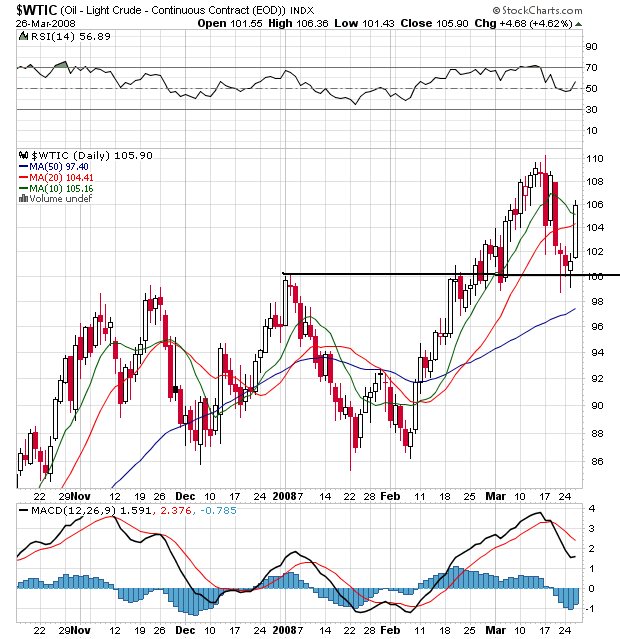

rude oil rose to its highest in more than a week after a pipeline explosion in southern Iraq, threatening to reduce exports.

The pipeline was on fire and the disruption will likely cut shipments to the Basra export terminal, an Iraqi official said. Iraq, holder of the world's third-largest crude reserves, ships most of the 2.32 million barrels it pumps each day from Basra.

``A setback like this and the militia activity in the last two days makes hopes for long-term peace and supply look fragile,'' said Robert Laughlin, a senior broker at MF Global Ltd. in London. ``We'd only just got used to Iraq supply becoming more reliable.''

The stock market is trading right where it was nine years ago. Stocks, long touted as the best investment for the long term, have been one of the worst investments over the nine-year period, trounced even by lowly Treasury bonds.

The Standard & Poor's 500-stock index, the basis for about half of the $1 trillion invested in U.S. index funds, finished at 1352.99 on Tuesday, below the 1362.80 it hit in April 1999. When dividends and inflation are factored into returns, the S&P 500 has risen an average of just 1.3% a year over the past 10 years, well below the historical norm, according to Morningstar Inc. For the past nine years, it has fallen 0.37% a year, and for the past eight, it is off 1.4% a year. In light of the current wobbly market, some economists and market analysts worry that the era of disappointing returns may not be over.

Until last fall, many investors had viewed the bursting of the tech-stock bubble as a nasty but short-term setback. The market had resumed its upward march, reaching new highs in October. Then the credit crisis began weighing on stocks, as did the possibility of a recession. By March 10, the S&P 500 was down 18.6% from its Oct. 9 record close, nearing the 20% decline that signals a bear market. It has rebounded since then amid the Federal Reserve's efforts to stabilize the financial system, but it remains 13.3% below its October record.

Conventional stock-market wisdom holds that if investors buy a broad range of stocks and hold them, they will do better than they would in other investments. But that rule hasn't held up for stocks bought in the late 1990s or 2000.

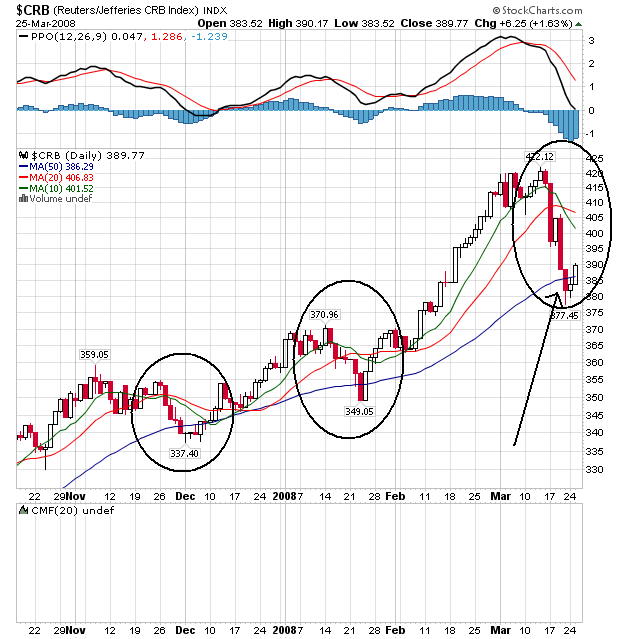

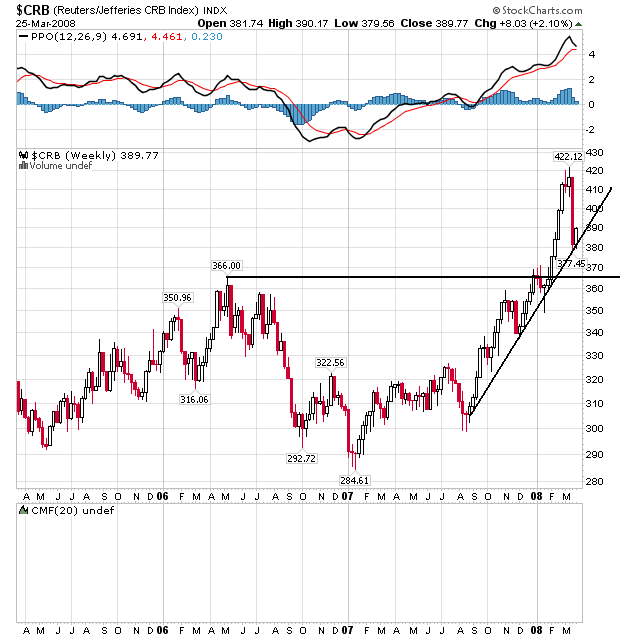

Over the past nine years, the S&P 500 is the worst-performing of nine different investment vehicles tracked by Morningstar, including commodities, real-estate investment trusts, gold and foreign stocks. Big U.S. stocks were outrun even by Treasury bonds, which historically perform much less well than stocks. Adjusted for inflation, Treasurys are up 4.7% a year over the past nine years, and up 5.8% a year since the March 2000 stock peak. An index of commodities has shown about twice the annual gains of bonds, as have real-estate investment trusts.

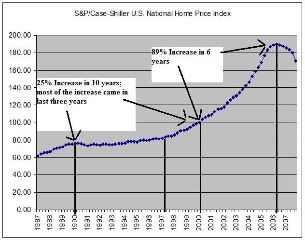

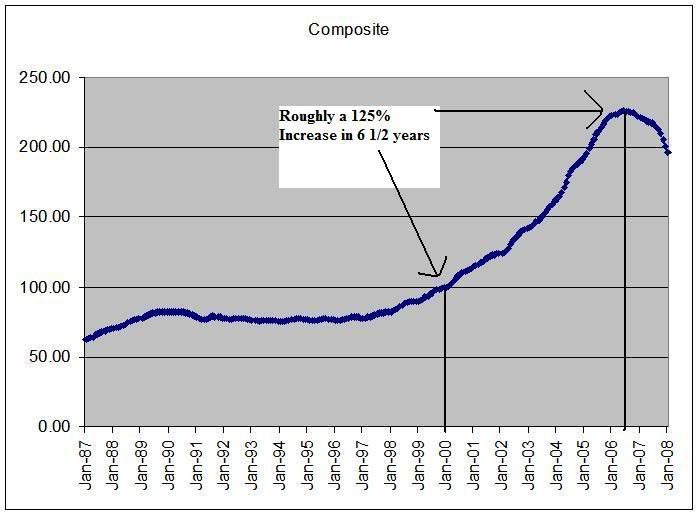

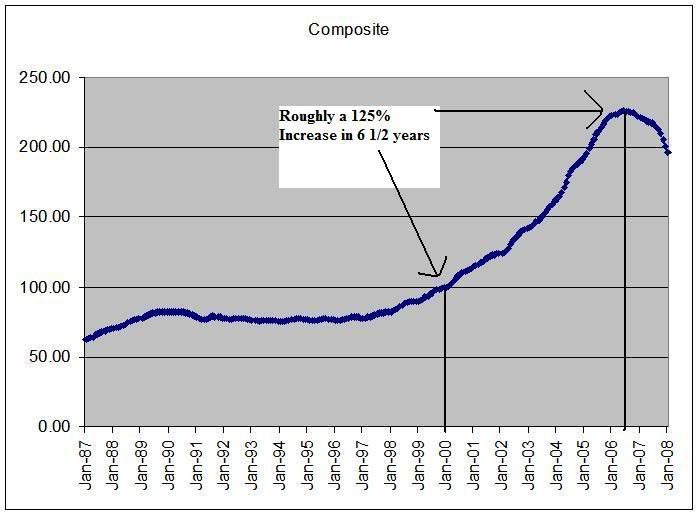

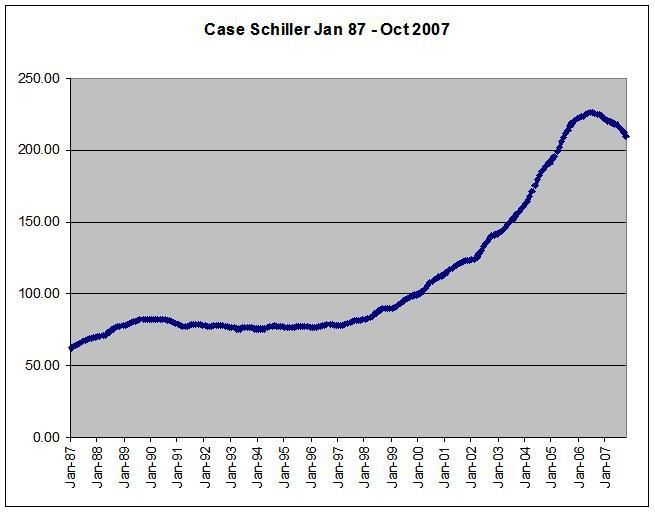

Home prices in many cities continued to plunge by record levels in January as sellers cut their asking bids and rising foreclosures took their toll, new data showed Tuesday.

While the spring selling season usually gives the market a bounce, some analysts say any notable improvement may not come until well into the summer. U.S. home prices fell 10.7 percent in January, and the Standard & Poor's/Case-Shiller home price index of 20 cities saw the steepest decline in the index's two-decade history.

A glut of foreclosed homes of historic proportions is starting to drive down U.S. home prices faster as lenders put more properties on the market and buyers show signs of interest.

The ability of America's lenders to manage this fire sale will be crucial to determining how long the housing market stays in the dumps -- and how quickly blighted neighborhoods can heal. The oversupply is severe: In some major markets, including Las Vegas and San Diego, foreclosure-related sales have accounted for more than 40% of all sales in recent months.

On Monday, new data suggested that pressures like these are starting to drive prices low enough to attract some buyers back into the market. Sales of previously occupied homes jumped 2.9% in February from the month before, the National Association of Realtors said, the first increase since July.

The median price dropped 8.2% from a year earlier to $195,900, the biggest drop recorded by the Realtors in the current slump.

In some beaten-down markets, the price cuts have been stark. The Detroit Board of Realtors recently found that home sales in the city (excluding suburbs) in the first two months of this year jumped 48% from a year earlier, to 1,540. The average home price there sank 54% to about $22,000.

'Got to Move Things'

Banks and others holding foreclosed property have concluded "we've got to move things" and are finally willing to slash prices, says Thomas Lawler, a housing economist in Leesburg, Va.

The supply is piling up fast. Overall, the total number of lender-owned homes doubled last year but sales grew only 4.4%.

Like many cities in the United States where the home vacancy rate has scaled its highest since records began in 1956, the former textile mill city of Worcester in Massachusetts is turning to the courts to fight back.

Their target: banks who abandon properties and who leave behind a glut of empty, dilapidated houses that draw crime, cut tax revenue and depress nearby property values in a market already in a tailspin.

......

The city of 175,898 people, a munitions depot during the U.S. Revolutionary War, offers a window into how U.S. cities are grappling with a wave of foreclosures that has pushed the U.S. homeowner vacancy rate to a record 2.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2007 -- or about 1 million homes.

Like many U.S. mayors and city officials, O'Brien blames "predatory" lending practices prevalent in the U.S. property boom for the lion's share of about 4,220 mortgages in his city that are either in, or at risk of, foreclosure.

.....

In western New York, the city of Buffalo filed a lawsuit on February 21 against 36 lenders -- including big names like JPMorgan Chase & Co Inc and Countrywide Financial Corp -- who were involved in 57 foreclosures that led to properties being abandoned and ultimately demolished by authorities.

The struggling Rust Belt city, plagued by about 10,000 vacant homes and commercial buildings, estimated the 57 foreclosures cost Buffalo $1 million in demolition work and another $1 million in nuisance costs -- from police patrols to boarding up buildings, to the social toll on communities.

.....

Further east, Syracuse, New York, began selling vacant homes last year for $1 each to non-profit groups who promise to tear them down or renovate them. Last month, Syracuse Mayor Matthew Driscoll extended the deal to private companies.

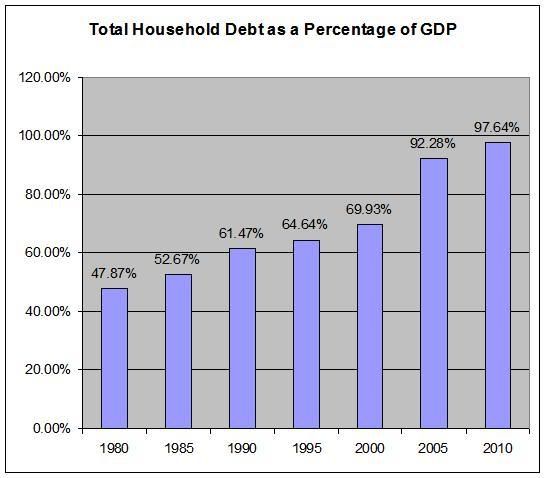

By the end of 2007, 36 percent of consumers' disposable income went to food, energy and medical care, a bigger chunk of income than at any time since records were first kept in 1960, according to Merrill Lynch.

AT LAST, WE MAY BE THERE. AFTER MONTHS OF TURMOIL capped by a run on a leading Wall Street house, banks and brokerage firms may finally have hit bottom. You can thank the multipronged regulatory response to the near-collapse of Bear Stearns. Those measures may well prevent the deeply depressed stocks of many financial outfits from sinking further. The shares may even start to recover, with encouraging implications for the entire market. Yes, after being down on financial stocks for more than a year, we find ourselves unable to resist some real springtime optimism.

Last week, the Federal Reserve slashed short-term interest rates, increasing the difference between short- and long-term rates, which typically boosts lenders' earnings. The Fed also opened its lending window to investment banks, giving them a new, stable, liquid source of funding. And regulators' decision to allow Fannie Mae (ticker: FNM) and Freddie Mac (FRE) to boost their investments in U.S. mortgages by $200 billion gave the mortgage market a big shot in the arm.

The market has yet to appreciate just how powerful those forces could be. Stocks of the industry's strongest players could climb by 10% to 20% over the next year as panic recedes, earnings improve and price-to-earnings multiples expand.

But make no mistake: Headlines will remain negative. Witness CIT Group's (CIT) report Thursday that it had lost access to short-term financing and Credit Suisse Group's (CS) warning of a first-quarter loss. Likewise, Standard & Poor's on Friday placed the debt ratings of Goldman Sachs Group (GS) and Lehman Brothers Holdings (LEH) on "negative outlook" because of earnings weakness. We fully expect economic growth will continue to decline, resulting in further loan losses. We wouldn't be surprised to see some of the weaker banks either go bust or turn to the industry's stronger players for a bailout.

But at this point, most of those risks are reflected in financial stock prices. And it won't be long before investors start looking at the second half of the year, when the worst of the write-downs should be over and earnings comparisons become much easier.

"From here, I think things are getting better, and the government and the Fed will do what they need to do when they need to do it," says Ernie Patrikis, a partner at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and former first vice president of the Federal Reserve of New York.