- by New Deal democrat

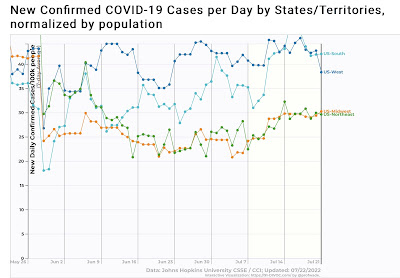

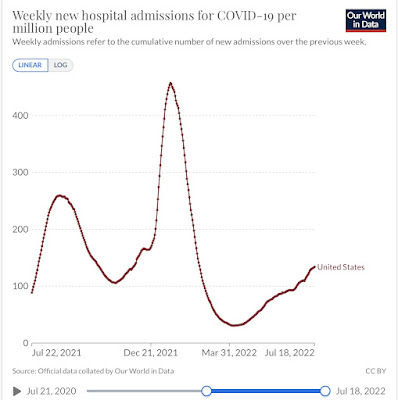

No important economic releases today, and almost no reporting by States as to COVID counts over the weekend, so let’s back up and take a look at something that’s been simmering on my intellectual back stove, so to speak: should the Fed be raising rates to combat this inflation? Has inflation already peaked? Or is the Fed way behind the curve and needs to raise rates a lot more?

Menzie Chinn has a guest post up, indicating that if the Fed had been following their own rules, they would have started raising rates during 2021. At the end of the day, I agree. Here’s why.

To begin with, I agree that if the sole sources of inflation are supply-based (the same amount of money chasing a shortfall in products), there’s no real point in raising rates. You can raise rates to 10% or 100%, if there’s a supply bottleneck, it’s not going to solve your problem; it’s just going to create lots of unemployment. In other words, for supply bottlenecks the best strategy is to leave high inflation alone, and don’t try to bring down employment.

But if inflation is demand based (more money chasing the same amount of goods as before), then raising rates to tamp down on demand makes sense.

Which one - or how much of each - do we have?

One good part of the answer is that inflation is global phenomenon, it’s not just limited to the US, as this chart helpfully put up by Kevin Drum shows:

If the source of inflation were US domestic stimulus, we wouldn’t see that type of global chart.

That suggests that, at least globally, the primary source of inflation is supply-based bottlenecks.

In the US, there have been 3 major sectors of inflation: energy (oil and gas), vehicles, and housing. Let’s look at them in order.

In the case of the price of gas, that did get tight by late last year, rising to $4/gallon over autumn and winter. But the real spike took place at the end of February, when Russia invaded Ukraine, and sanctions were imposed:

This is a supply shortfall, caused by a geopolitical event. Per my note above, the Fed shouldn’t be raising rates because of gas prices.

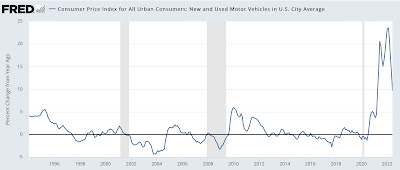

Next is motor vehicles:

These spiked due to a computer chip shortfall sourced to Chinese and Taiwanese factories, in large part due to those governments’ “zero COVID” or strict lockdown policies. Again, this is a supply shortfall and raising rates is not going to cause either jurisdiction to make more computer chips (If I were Biden, I would have invoked the Defense Production Act long ago to substitute US-made chips during the COVID emergency, but that’s another issue)

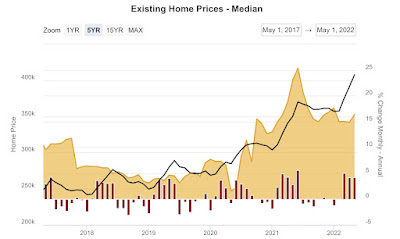

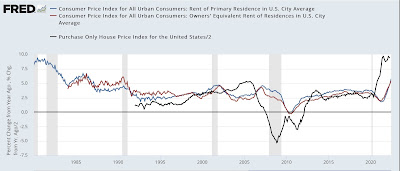

Finally, here is housing:

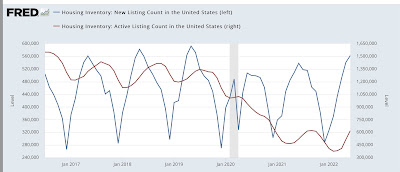

Housing appears to have strong elements of both supply *and* demand at issue. On the supply side, existing homeowners more or less stopped putting their houses up for sale even before COVID hit, and definitely during the teeth of the pandemic:

Only now is increasing inventory coming on the market.

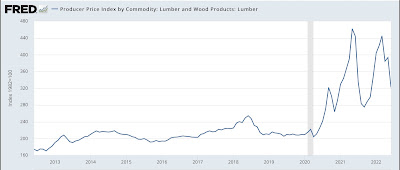

Further on the supply side, the price of lumber in particular skyrocketed:

This caused a huge backlog of houses under construction that were not completed:

But on the other hand, it’s also clear that extremely low interest rates, with record low monthly mortgage payments in “real” terms spike a surge in demand:

As night follows day, the record surge in house prices in 2021 and so far in 2022 has spilled over into rent increases and thereby in “owners’ equivalent rent,” the official CPI measure of housing inflation (we’ll come back to the black line, real GDP, later):

Housing is 33% of the entire CPI, and over 40% of core CPI.

So, is the main driver a shortfall in housing supply, or a surge in housing demand?

To look at that, I compared the growth in the total US population since the turn of the Millennium with the total amount of housing stock available in the US, which is helpfully estimated by the Census Bureau:

And the answer is, the available amount of housing stock has indeed kept up with population growth (by the way, this would be true even if I had measured from the worst possible comparison point just before the Great Recession). While there are certainly particular areas where that has not been true, and prices have been nuts for a long time (California!), the simple fact is that, averaged over the country, that is not the case.

In other words, housing inflation is primarily a demand, not a supply, issue, and since it is the single biggest slice of the CPI, that should have started to be addressed by the Fed once real GDP caught back up to its pre-pandemic levels, which according to the black line in the graph above was Q2 of 2021.

Had the Fed started raising rates then, it would have been attacking a CPI level of about 4%, and would have had a much better chance of obtaining a “soft landing” than it has now. In fact, the only way I see of the US avoiding recession at this point is if gas prices move all the way back down to the $4/gallon level, very soon, and stay there or below.