- by New Deal democrat

As you know, I’ve been monitoring initial jobless claims closely for the past several months, to see if there are any signs of a slowdown turning into something worse. Simply put, if businesses aren’t laying employees off, those same people are consumers who are going to continue to spend, which is 70% of the total economy. So the lack of any such increase has been the best argument that no recession is imminent.

This morning’s report of 252,000 initial claims is enough to signal a caution, but historically has more often coincided with slowdowns rather than recessions.

To reiterate, my two thresholds for initial claims are:

1. If the four week average on claims is more than 10% above its expansion low.

2. If the YoY% change in the monthly average turns higher.

I’ve also added a threshold for the less leading, but also much less volatile 4 week average of continuing claims at 5% higher YoY.

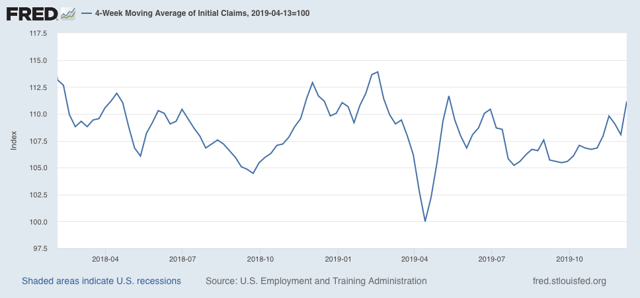

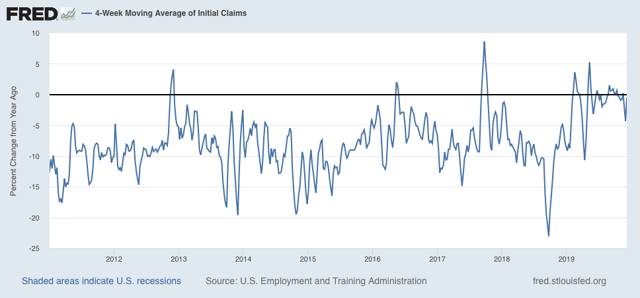

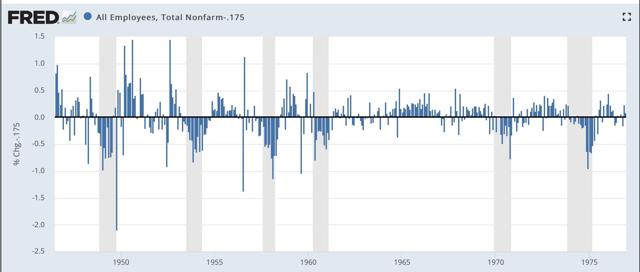

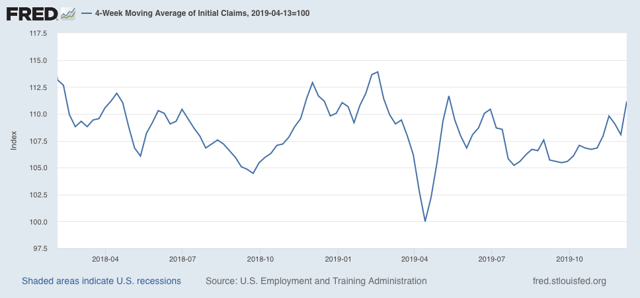

This week’s reading of 252,000 was the weakest since September of 2017. As a result, the 4 week moving average of claims has risen to 224,000, is 11.2% above the lowest reading of this expansion, which occurred back in April:

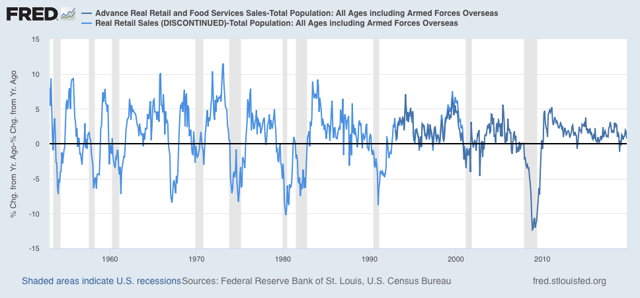

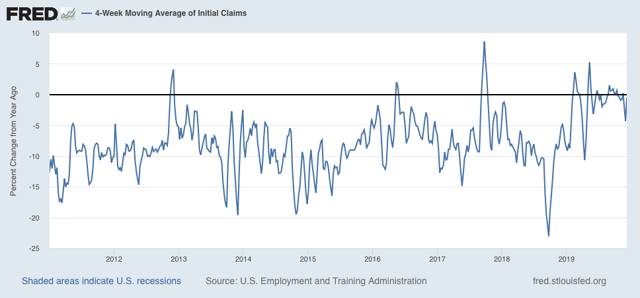

Nevertheless, on a YoY% change basis, the 4 week average is still slightly below, as in by 1,000 or -0.5%, its level one year ago:

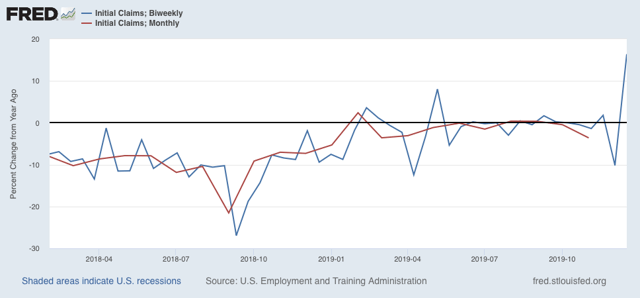

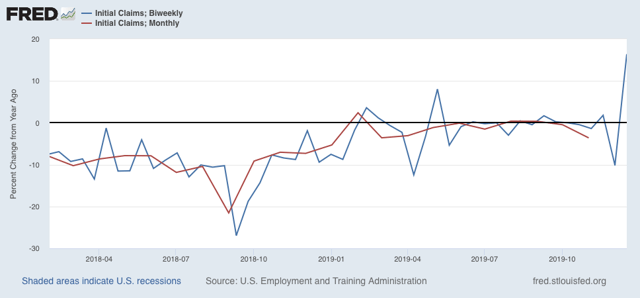

For the first two weeks of December (blue in the graph below), the average is 226,000 vs. 223,200 for the entire month of December last year (red), or higher by 1.3%, while on direct comparison with the first two weeks of last December, they are higher by 4.4%:

Both thresholds for concern - extra watchfulness - have been met.

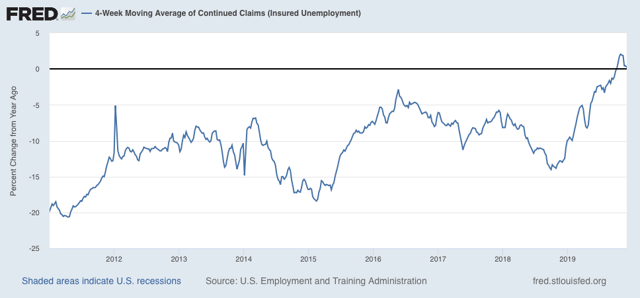

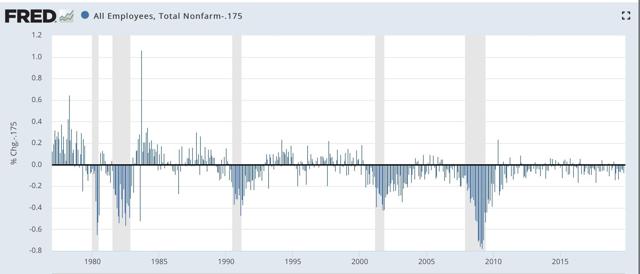

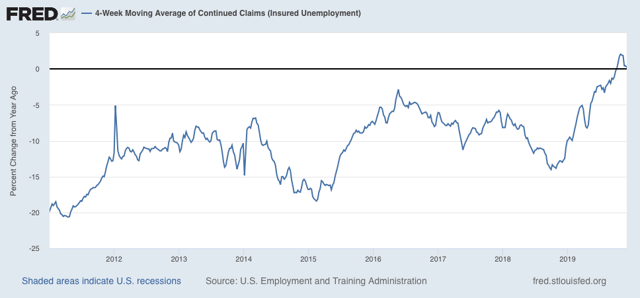

Meanwhile, the less volatile 4 week average of continuing claims is 0.2% above where it was a year ago:

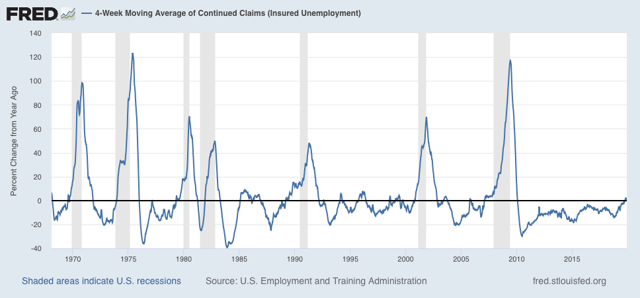

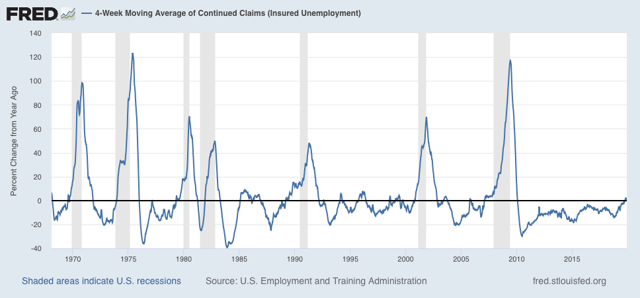

Here is the longer term graph:

Again, this certainly is cautionary, and is consistent with a significant slowdown. But there have been similar readings in 1967, 1985-6, 3 times in the 1990s, and briefly in 2003 and 2005, all without a recession following. So the threshold for continuing claims being a negative (vs. neutral) has not been met either.

Several weeks ago I wrote that “unless initial claims start to be reported in the 230’s, and continuing claims continue to trend higher, into the 1.770 million range (by mid-December, after which the YoY comparisons for continuing claims get much easier), no interim recession will be signaled.” Last year we also saw some seasonal weakness in initial claims, even before the government shutdown, so one bad week is not enough reason for a fundamental change of opinion beyond turning neutral. So it will take several more weak weeks of readings in the 230’s or worse for initial claims to raise a red flag.