-

by New Deal democratLike a roller coaster at the bottom of that terrifying first drop, the leading part of the economy has turned up, but the lagging part continues to drop. That's the message from this past week's economic statistics, which focused heavily on manufacturing and jobs. Manufacturing has surged into growth. Jobs continue to decline and unemployment claims are stubbornly high. As to whether we will have a V-shaped jobs recovery, or a "jobless recovery" that requires strong GDP growth just to generate a single additional new job, the answer appears to be, "both." I'll explain why that is below the fold.

I. Manufacturing has surged into growthThis is likely to be an old-fashioned recovery, where manufacturing leads the way. This past week we got a slew of data about the strength of the manufacturing rebound. Most importantly, the

Institute of Supply Management's manufacturing index recorded outright growth, it's reading of 52.9 (above 50 indicates growth) was not only significantly higher than estimates, but according to the ISM, "the highest since June 2007." The new orders index likewise surged, "up 9.6 points to 64.9 percent, the highest since December 2004." The deliveries index, a leading indicator, also improved to 57.1. Inventories shrank, meaning that replacing goods on shelves will require more manufacturing in the future.

here's the chart:

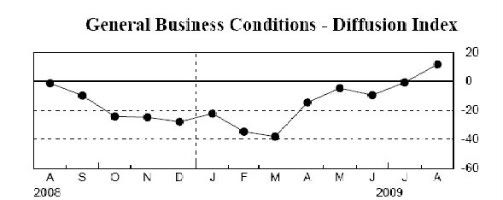

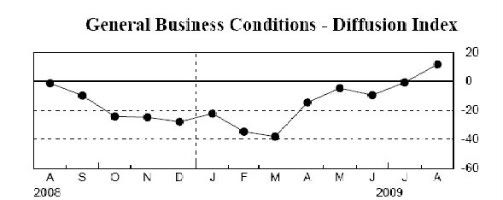

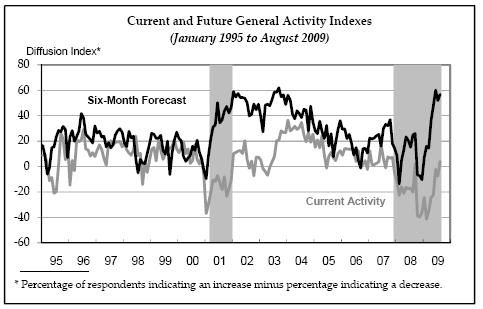

The ISM index confirmed prior readings of expansion by the Federal Reserve Bank districts of New York:

Philadelphia:

and Richmond:

And

Reuters reported that:

A similar index covering the heavily industrialized Milwaukee region rose to 56 in August from 45 in July,

Auto and truck sales also showed a dramatic "pop" due to "cash for clunkers," and factory orders and durable goods also showed strength,

although new orders for consumer nondurable goods, the only poor item of data, declined 1.9%, remaining the only leading indicator not to have turned up in the last 6 months.

Yesterday's report showed that manufacturing workweek and overtime were steady, neither improving nor declining from July.

In short, this week the data began to paint the picture of a robust recovery in manufacturing

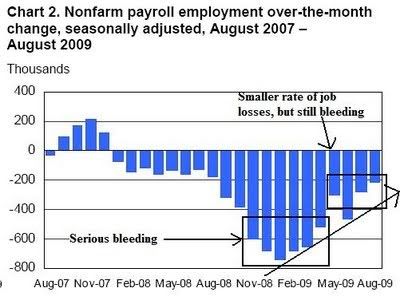

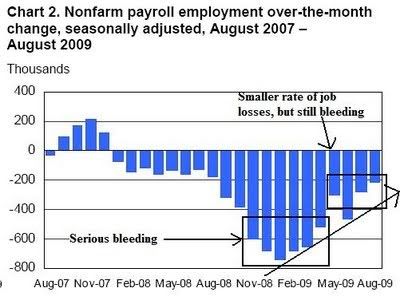

II. But employment and unemployment data remain weak.While manufacturing strengthened, this did not feed through into job growth. Yesterday the BLS reported that the US economy shed ( - 216,000) jobs in August, a modest improvement over July's negatively revised ( - 276,000).

This was in line with

private reports from earlier this week, and the Institute for Supply Management's manufacturing and non-manufacturing surveys, which showed similar improvement but still more businesses laying off than hiring.

Meanwhile, new jobless claims remain stubbornly high at about 570,000 a week (seasonally adjusted). That means that there is a gradual increase in hiring taking place, but not enough to offset the continued firing of employees. Employers simply aren't ready to add new workers yet. Instead, they're handling increased orders by working existing employees harder.

Still, both trends (of jobless claims and payroll unemployment) are moving in the right direction. For example, as in past recessions and recoveries, the sequence is that initial claims peak first, then 5-14 weeks' continuing claims, then 14-26 weeks and finally 27 plus weeks, the last one usually after the recession is over (blue, then orange, then green, then red in the graph below). Not only is the same sequence followed now, but for the first time there is evidence that claims of 27 weeks plus are peaking (which typically only happens once the recession is already over):

Further, in

every prior recession, mean duration of unemployment has peaked at or after the end of the recession:

Notice that mean duration of unemployment has already peaked in 2009.

Nevertheless, these employment and unemployment reports show continued pain, and especially given the huge number of people who have been unemployed for a very long period of time. Most significantly, there a more longer term unemployed now than during any post World War 2 recession.

III. How manufacturing strength and job weakness fit together

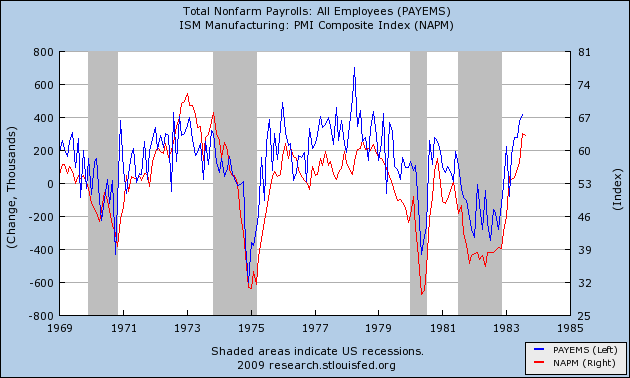

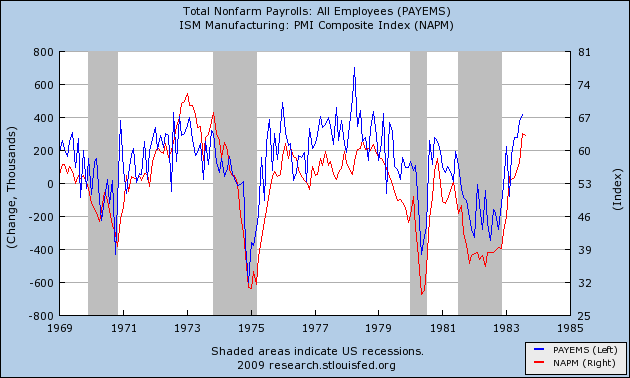

III. How manufacturing strength and job weakness fit togetherIn Part I above I highlighted the ISM manufacturing index, which surged from contraction to expansion in August. How well does this index's reading of expansion correlate with job growth? As it turns out, manufacturing growth and increased employment correlate very well. This tells us a lot about what to expect in the next few months. Let me show you how well the two data series fit, below.

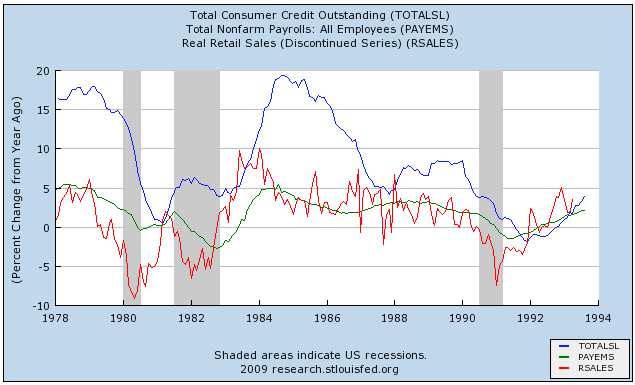

First, here is a graph covering the years 1969-1983, including 4 recessions and recoveries. The jobs numbers are in blue, left scale, and the ISM manufacturing index is in red, right scale:

First of all, notice how closely the two series correlate with one another. If you are having any problem reading the squiggles, here's what they show: in these traditional recoveries, with a few months during the 1970-71 recession and recovery, an ISM manufacturing reading above 50

almost perfectly correlated with actual job expansion. For example, the 1982 deep recession (which featured U3 unemployment over 10%) ended in November 2002. Here are the next ISM manufacturing readings:

1982-12-01 42.8

1983-01-01 46.0

1983-02-01 54.4 ( -78,000)

1983-03-01 53.9 +173,000

1983-04-01 54.2 +276,000

1983-05-01 56.1 +277,000

Notice that the

first month of growth shown by the ISM index nevertheless coincided with a negative jobs number. Keep that in mind later.

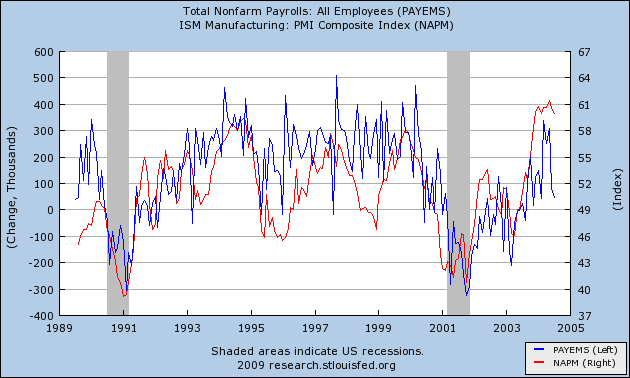

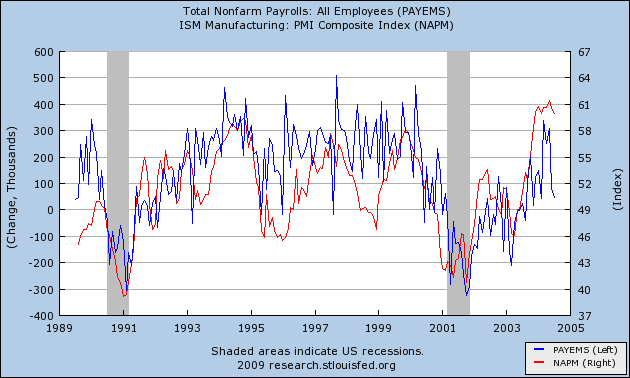

Next, let's look at the graph for 1989-2004. This includes our two previous "jobless" recoveries:

Once again, the correlation is striking, but this time -- particularly after the 2001 recession -- there were some weakly positive ISM readings that nevertheless were accompanied by negative jobs reports. This is because both were

very weak manufacturing expansions. In contrast to the 1950s-1970s recoveries,

at no time during either of the more recent "jobless recoveries" was there an ISM manufacturing index reading of 54.0 or aboveLet's look at them in turn. The 1990 recession ended in March 1991, but employment declined until May. Unemployment didn't peak until June 1992. Although throughout that period, typicially the economy did add jobs, unemployment still rose. You need ~150,000 new jobs every month to keep up with population growth, and the recovery wasn't strong enough.

The ISM manufacturing index first turned positive in June 1991, turning negative for 3 months at the end of the year, before rebounding again. During the period betwen June 1991 and the June 1992 peak, ISM readings above 50 meant positive jobs data with two exceptions:

1991-07-01 50.6 (-47,000) (only the

second month after it turned positive)

1992-02-01 52.7 (-66,000) (the

first month after the index turned positive again)

Aside from that, a positive ISM reading correlated perfectly with positive jobs data.

Next, let's look at the 2001 recession. Despite ending in November 2001, unemployment did not peak until June 1993, and employment continued to decline until August 1993. This time, the "recovery" was so weak, job growth was almost non-existent.

The ISM manufacturing index first turned positive in February 2002. During the period betwen then and August 2003, the ISM index vacillated between expansion and contraction, never recording a higher number than 53.6 in June 2002. There were a number of negative job readings. Here are the two worst along with relevant subsequent months:

2002-02-01 50.7 ( -147,000) (the

first month after the ISM index initially showed growth)

2002-03-01 52.4 (-22,000)

2002-04-01 52.4 (-85,000)

2002-05-01 53.1 ( - 7,000)

2002-06-01 53.6 +45.000)

----------------------

2002-12-01 51.6 ( -156,000) (the

first month after it rebounded into growth)

2003-01-01 51.3 +83,000

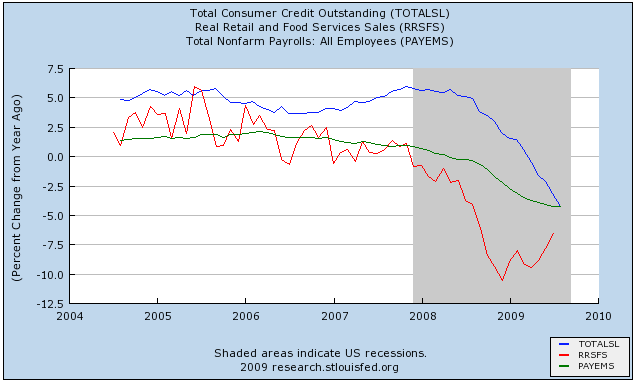

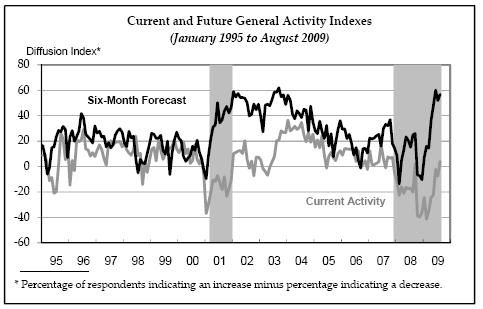

Finally, let's look at the recent "Great Recession" and the present incipient recovery:

Notice again how well the two series correlate with one another. In this, our

first month after manufacturing returned to growth, the economy subtracted ( -216,000) jobs.

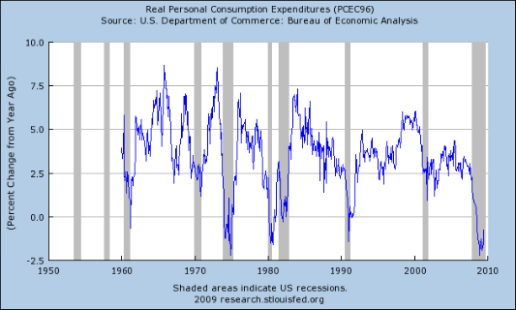

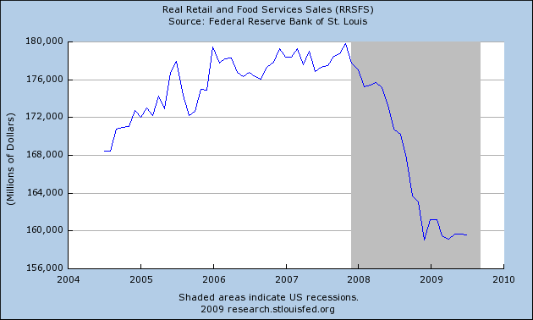

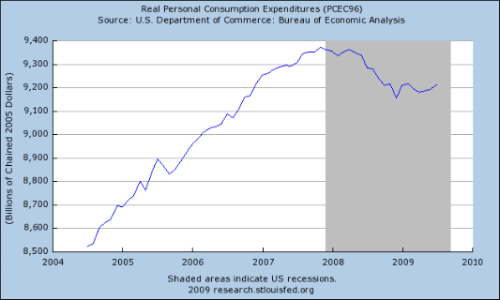

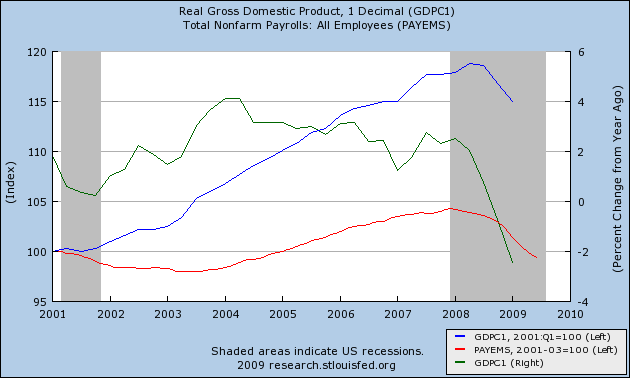

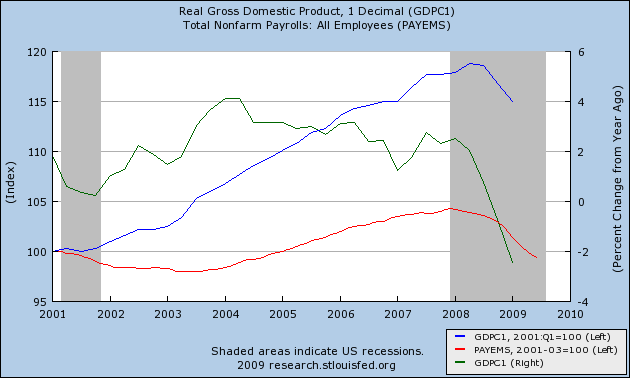

You may recall that I showed a few weeks ago how "Okun's law" about GDP growth and job growth appeared to have been "broken", or at least changed. Since about 1995, it takes 2% GDP growth to add a single net job to the American economy. Here's the graph I used then:

The recent initial jobless claims, payroll, and unemployment data strongly indicates that those metrics remain true. Merely having manufacturing return to growth isn't enough to generate new jobs. The growth must be strong enough to overcome the drag of outsourcing and "productivity." So, will it be?

IV. The Leading Economic Indicators will probably print positive for the 5th straight month in August The very same data that told Bonddad and me four months ago that the economic free fall was going to stop, and that has ever more strongly pointed to recovery, the Leading Economic Indicators, are now known for August, and it looks like it will be another decent month. I'll spare you the multitude of graphs, but here's the list (with my estimates of their contribution to the index):

The yield curve is still positive +02

Stocks' 3 month gain is worth +0.1

New home sales are worth about +0.1

Durable goods' strong growth add +0.2

Consumer sentiment adds +0.1

ISM deliveries up strongly, adding +0.1

Aggregate hours in manufacturing were unchanged 0

Jobless claims were slightly worse -0.1

Real M2* has been trending slightly negative, so -0.1

Consumer nondurables down strongly -0.2

Bottom line: it looks like August Leading Economic Indicators (and revisions to July) will net about +0.4, the fifth positive reading in a row.

Finally, just yesterday, the Economic Cycle Research Institute, a forecasting service that dates to before the Great Depression,

reiterated its very bullish stance:

A weekly measure of future U.S. economic growth rose in the latest week, while its yearly growth rate surged to a 38-year high that suggests the recovery is on track.

The Economic Cycle Research Institute, a New York-based independent forecasting group, said its Weekly Leading Index rose to 124.7 in the week to August 28 from a downwardly revised 124.3 in the previous week, originally reported as 124.4.

The index's annualized growth rate rose to 20.8 percent from 19.6 percent a week earlier. The latest reading was the index's highest yearly growth rate since the week to May 21, 1971, when it stood at 21.3 percent.

Conclusion: To the Question, "Will it be a V-shaped jobs recovery, or a 'jobless recovery'", the answer seems to be "Both." To sum up:

1. Job loss in the recession -- about 8 million and wiping out an entire decade of growth -- has been terrible and remains persistent even as the leading parts of the economy -- housing and manufacturing -- have actually started to grow again. Unlike the earlier post-World War 2 recoveries, in the past decade it has taken strong economic growth of 2% or more just to generate a single new American job. The indications certainly are that the same headwind - aided and abetted by offshoring - persists and will remain a blight on the economy.

2. Meanwhile, manufacturing has undergone a breathtaking turnaround. The manufacturing index's average change of +3.3 in the last 5 months is a stronger move than in either of the two previous "jobless recoveries." In the 2002-3 recovery, manufacturing stalled out, never raising the index above 53.6. In contrast, in early 1983 the manufacturing index quickly rocketed to 56.1, adding a quarter million jobs in that month. That is the same type of growth that ECRI is predicting in the quote above.

3. We will probably continue to experience job losses if housing and manufacturing stall out here.

4. But the ISM deliveries subindex is part of the LEI, and that index continues to move in a positive direction.

5. So in conclusion, the odds favor the manufacturing index continuing to rise in the next several months, and if that happens, then despite the headwind of needing to have 2% GDP growth to generate jobs, we may nevertheless see job growth shortly.

================

Post Script: Conclusively proving that I Have No Life, I have spent considerable time since I drafted the above looking for a better leading indicator for when job growth did ultimately occur after the 1991 and 2001 recessions. Part 3 above is a good first stab at it, I think, but I would like to be more confident in that part of the analysis. In other words, hopefully a more refined analysis with more confident conclusions, soon.