- by New Deal democrat

There’s no significant new economic news today, so let’s take a look at something of a topic du jour.

In case you haven’t seen it elsewhere, “economic policy uncertainty” has spiked to a level never seen before aside from the moment the pandemic hit and caused lockdowns in March 2020:

This has been seen as increasing the odds of a recession, perhaps immediately.

So I decided to explore two facets of this possibility:

(1) is there any evidence of any immediate downturn in hard business or consumer data?

(2) in prior episodes of major spikes in such uncertainty, have business investment and/or consumer spending responded immediately, with a delay, or has there been no correlation?

As to the first aspect, as you know I track high frequency data and report on it each week. Although I don’t have a graph to show you, in terms of business investment I do track the new orders components of the five monthly regional Fed manufacturing surveys.

After languishing for most of two years, at the end of December the average was -5, indicating slight contraction. At the end of January the average had risen to +6 on the back of particularly strong NY and Philly regional reports, and at the end of February it had only changed -1 to +5. So far only the NY Fed has updated for March, but it has shown a significant decline of -26.3, which has taken the average of the index to -1, i.e., generally neither expanding nor declining. This is too weak a reed to cite for any significant change of direction. At very least the other regional Feds’ reports will have to come in before it can be suggested with any probity that business investment has begun to decline.

As for consumer behavior, every week Redbook updates same store spending. Here i do have a graph, and here is what it looks like for the past three years:

As of last week, spending was up 5.7% YoY. For the last four weeks, it has averaged 6.1%. In short, there is no discernible wavering in consumer spending as of the latest data.

Now let’s look at past history.

To track the response of business investment, I looked at manufacturers’ new orders, both in total (red in the graphs below) and for durable goods (gold), compared with policy uncertainty (inverted, /10 for scale). First is the long term historical view. It is averaged quarterly because the month to month variation is far too noisy to see any pattern:

There is no discernible pattern when the changes are very minor. But when we look on a YoY basis quarterly, you can see that significant changes in policy uncertainty lead new orders for goods by an average of 2 to 3 quarters. The effect is far less noisy as to total orders than it is for durable goods orders. This is not to say, by the way, that the former *causes* the latter. It is simply to say that, whatever the reason for the former, changes in the latter do appear to occur, but with a significant lag.

Now here is a monthly close-up post pandemic:

You can see that policy uncertainty went from very good readings to neutral as of the beginning of 2022. New orders followed with roughly a twelve month lag. As of the most recent data for new orders as of January, there has been no significant change.

Next let’s look at the same comparison, using real retail sales (red) and real personal spending on goods (g0ld) as our proxies for the consumer. Again the historical look is quarterly to cut down on noise:

The consumer response appears much more coincidental to episodes giving rise to more uncertainty, lagging on average only one quarter and sometimes not at all.

Now here is the post-pandemic view:

There has been no discernible reaction so far.

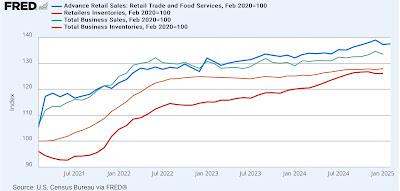

Finally, below is a graph of policy uncertainty compared with *both* manufacturers total new orders (gold) as well as real retail sales (red):

This makes it easier to see that usually (but not always!) the consumer reaction has come first, before the reaction by manufacturers. This is of a piece with the idea that sales lead production and inventories (something I have shown in the past), as manufacturers react to increased or decreased demand, rather than anticipating it.

This time could always be different. In particular, the motor vehicle industry has been heavily integrated across national lines in North America. The turning off of that spigot may very well have immediate and dramatic effects. But I think the takeaway here is to continue to keep an eye on the high frequency investment and spending data, with the expectation that the consumer spending data is likely to show a significant repsonse first.