Saturday, August 8, 2015

Weekly Indicators for August 3 -7 at XE.com

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicator post is up at XE.com. Last week's poor tax withholding report was as anticipated an aberration, but most coincident indicators remain weak.

On a broader note, I am increasingly convinced that we are past the midpoint of this expansion - probably in the 6th inning, to use a baseball analogy. But that doesn't mean that I have turned negative, or that a recession is near. Basically it just means that we are getting less "bang for the buck" from the fundamental trends that have underpinned the expansion.

Friday, August 7, 2015

Demographic pressure is driving demand in the US housing market

- by New Deal democrat

My second article on the US housing market, explaining how real demand is driving prices, is up at XE.com.

The Pied Piper of Doom and The Automatic Earth: commodity collapse edition

- by New Deal democrat

Doom sells. That's the simple fact. Whatever you may think of their substantive record, you have to ruefully appreciate Zero Hedge's business model: if Doom sells, then the way to really monetize economic commentary is to aggregate Doom! And boy howdy has it ever worked. For them.

I mention this because there is yet another Doomgasm going on in the place where I started bloggging, this time about the collapse in commodity prices. So why be bothered?

Because here's a few of the comments by the financially unsophisticated readers, particularly after the Pied Piper of Doom touted the blog "The Automatic Earth:"

Causing this kind of unfounded panic makes my blood boil (although, to his credit, the author of the article is not calling for an economic crash, despite the Apocalyptic title he chose for his piece).

So let's cut to the chase. What is the meaning of the commodity collapse"

1. sucks to be China

2. really sucks to be a supplier of China

3. Teh Awesome to be a consumer of products.

Why? Prices, supply and demand for industrial commodities are set globally, not locally. A comodity price decline usual ly happens because manufacturers are using less commodities, i.e., there is a manufacturing recession. Commodiity prices go down more than produceer prices, and producer prices go down more, or increase less than consumer prices.

Here's the best example I have read. In the late 1800s, one of the most important things happening in the US was the building of railroads. Each year new track would be laid down. So suppose in a given year railroads lay down 4,000 miles of track. Then the next year they lay down 2,000 miles of new track. Even though there is now a total of 6,000 miles of new track, the suppliers of track saw their sales fall by 50%. Ouch! But rail passengers benefitted from the rail lines.

Ironically, the best evidence indicating that consumer countries have little to fear from a commodity collapse comes from ECRI, which sevcral years ago published a presentation on "Yo Yo economies", in which they wrote:

It is necessarily true that if supplier economies are especially vulnerable to cyclical fluctuations, then economies which are primarily consumers of end stage goods, like the US, are the least vulnerable. If supplier economies are especially unable to decouple, then it followers that consumer economies are the most likely to be able to approach decoupling.

Elsewhere in their presentation they wrote:

As if that weren't clear enough, ECRI supplied this very helpful graph:

Notice that the arrow at the top for consumer countries in ECRI's diagram is still pointing UP.

Think of the middle line as China, the bottom line Australia and Canada, and the top line as the US. In fact, the situation is probably better than that for the US, because the premise of the graph is that there is a consumer slowdown. ECRI then calculates the effect on suppliers. But here, the consumer slowdown is taking place in China. So there is no reason to think that other consumming countries, like the US, will slow down.

But to turn back to the article in question, as to which the Pied Piper of Doom touts a recent piece on the blog "The Autormatic Earth." What were the y saying back in the Great Recession? Well, here's what they though was goiong to happen as of December 12, 2008:

And the two author of the piece today and the Pied Piper of Doom, who is touting The Autormatic Earth ? Here's their financial insight, only two months after the stock market bottom, on May 12, 2009,:

So anybody who takes advice from them about what to do with their money is playing with fire, to say the least. Caveat reader.

Doom sells. That's the simple fact. Whatever you may think of their substantive record, you have to ruefully appreciate Zero Hedge's business model: if Doom sells, then the way to really monetize economic commentary is to aggregate Doom! And boy howdy has it ever worked. For them.

I mention this because there is yet another Doomgasm going on in the place where I started bloggging, this time about the collapse in commodity prices. So why be bothered?

Because here's a few of the comments by the financially unsophisticated readers, particularly after the Pied Piper of Doom touted the blog "The Automatic Earth:"

"Articles like this make me feel like deer in the headlights.

"Really, if true, how the hell is one expected "to prepare" for that scenario?"

---

"Yes, please. I am reading the Ilargi piece."

---

"Reading the comments to this article, I gather one is to liquidate all assets in banks and brokerages...then, what? Keep them under the mattress?"

Causing this kind of unfounded panic makes my blood boil (although, to his credit, the author of the article is not calling for an economic crash, despite the Apocalyptic title he chose for his piece).

So let's cut to the chase. What is the meaning of the commodity collapse"

1. sucks to be China

2. really sucks to be a supplier of China

3. Teh Awesome to be a consumer of products.

Why? Prices, supply and demand for industrial commodities are set globally, not locally. A comodity price decline usual ly happens because manufacturers are using less commodities, i.e., there is a manufacturing recession. Commodiity prices go down more than produceer prices, and producer prices go down more, or increase less than consumer prices.

Here's the best example I have read. In the late 1800s, one of the most important things happening in the US was the building of railroads. Each year new track would be laid down. So suppose in a given year railroads lay down 4,000 miles of track. Then the next year they lay down 2,000 miles of new track. Even though there is now a total of 6,000 miles of new track, the suppliers of track saw their sales fall by 50%. Ouch! But rail passengers benefitted from the rail lines.

Ironically, the best evidence indicating that consumer countries have little to fear from a commodity collapse comes from ECRI, which sevcral years ago published a presentation on "Yo Yo economies", in which they wrote:

The rising export dependence of these [suppliers of suppliers] economies, with growing involvement in global supply networks, makes it increasingly difficult for economies to decouple, especially for suppliers of early-stage goods that have embedded themselves further up the supply chain and farther away from the final consumer. This makes them highly vulnerable to the Bullwhip Effect and at the mercy of cyclical fluctuations in end-user demand growth.[my emphasis]

It is necessarily true that if supplier economies are especially vulnerable to cyclical fluctuations, then economies which are primarily consumers of end stage goods, like the US, are the least vulnerable. If supplier economies are especially unable to decouple, then it followers that consumer economies are the most likely to be able to approach decoupling.

Elsewhere in their presentation they wrote:

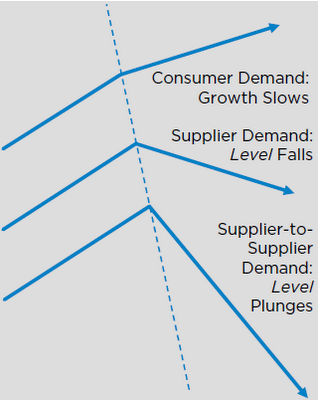

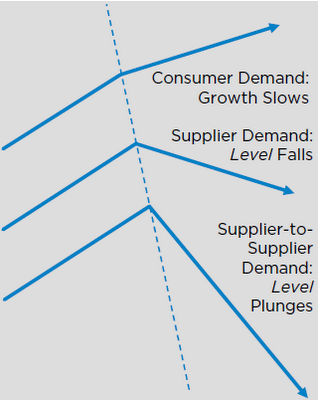

[D]eveloping economies are very much subject to the Bullwhip Effect, where small fluctuations in consumer demand growth get amplified up the supply chain into big swings in demand as we move away from the consumer. So, smaller shifts in end consumer demand growth translate into larger fluctuations in intermediate goods demand, and even bigger ones in input material demand, and especially, raw material prices.In other words, an absolute contraction in supplier countries can be caused by simply continued growth, but at a slower rate, in a consumer country. Which means that converse is also true: an observed contraction in supplier economies (like China) does not necessarily mean that there is a contraction in consumer economies (like the US). Rather, consumer economies may simply continue to grow, just at a slower pace.

Even a modest decline in consumer spending growth in developed economies like the U.S. and Europe can help trigger a significant downdraft in the level of demand from suppliers and, in turn, a serious downturn in the level of demand for “suppliers to suppliers.”

As if that weren't clear enough, ECRI supplied this very helpful graph:

Notice that the arrow at the top for consumer countries in ECRI's diagram is still pointing UP.

Think of the middle line as China, the bottom line Australia and Canada, and the top line as the US. In fact, the situation is probably better than that for the US, because the premise of the graph is that there is a consumer slowdown. ECRI then calculates the effect on suppliers. But here, the consumer slowdown is taking place in China. So there is no reason to think that other consumming countries, like the US, will slow down.

But to turn back to the article in question, as to which the Pied Piper of Doom touts a recent piece on the blog "The Autormatic Earth." What were the y saying back in the Great Recession? Well, here's what they though was goiong to happen as of December 12, 2008:

Last month I started warning of millions of lay-offs to come in the US economy. Since then, we've seen a November job loss of 533.000, as well as predictions of pink slip totals of a million and more every single month in 2009. ...

[S]upermarket shelves will be as empty as electronics stores ....

Banking and investing as we've known it won't be back for at least decades. The upcoming round of bank failures, which will leave very few, if any, standing, cannot be prevented.

Umm, no.

The stock market bottomed in March 2009. What were they saying then?

On March 2 they wrote:

The stock market bottomed in March 2009. What were they saying then?

On March 2 they wrote:

The US Government throws 30 billion more pearls before the swine at AIG.... [note: the US actually made a profit on its AIG investment, which was paid back in full]

The downturn is nowhere near over, or at a bottom, or anything like that. It will not be a straight line down, but the trendline is certain. Many pundits now claims that a Dow at 5000 is some sort of bottom, but don't count on it. As for home prices, they will keep tumbling and lose at least 80% of their peak values.

[note: house prices bottomed at the beginning of 2012, about 30% under peak values].

On March 4 they wrote:

Almost 700,000 Americans lost their jobs in February, which is 100,000 more than in January. The revised versions of those numbers will be between 10% and 20% higher. .... So I assumed that for the rest of 2009 pink slips will rise by 100,000 every month compared with the month before. That is, for the sake of scribblings I pretend that the economy will not deteriorate exponentially. I know that takes a lot of pretending, but since the results are bad enough even when I pretend, I'll stick with it.

The total number of jobs lost would be about 13.7 million on December 31.

Peak job losses were recorded at -824,000 in April. While January was revised higher, February wasn't. Job losses didn't increase 100,000 per month, let alone exponentially, on average they *decreased* 100,000 per month after that. So they were only off by about 10,000,000 jobs in their "conservative" estimate.

And on March 9, 2009, the exact day of the stock market bottom, they wrote:

Warren Buffet says that stocks are the best investment ... It won't be for all of the millions of investors who take his advice. Why would anyone listen to [Buffet], ... it's beyond me.

Pied Piper of Doom: "Shifted to 75% Cash/Bonds Friday!"

The author of the piece about the commodity crash today: "The rally is done. .... If you are buying now you are simply giving your money away. Now is the time to go to cash. Maybe in a few months things might be different."

Of course, instead the stock indexes have more than doubled since then.

The author of the piece about the commodity crash today: "The rally is done. .... If you are buying now you are simply giving your money away. Now is the time to go to cash. Maybe in a few months things might be different."

Of course, instead the stock indexes have more than doubled since then.

So anybody who takes advice from them about what to do with their money is playing with fire, to say the least. Caveat reader.

July jobs report: good, but evidence that this expansion is in its 6th or 7th inning

- by New Deal democrat

HEADLINES:

- 215,000 jobs added to the economy

- U3 unemployment rate unchanged at 5.3%

With the expansion firmly established, the focus has shifted to wages and the chronic heightened unemployment. Here's the headlines on those:

Wages and participation rates

- Not in Labor Force, but Want a Job Now: up +59,000 from 6.076 million to 6.135 million

- Part time for economic reasons: down -180,000 from 6.505 million to 6.325 million

- Employment/population ratio ages 25-54: fell from 77.2% to 77.1

- Average Weekly Earnings for Production and Nonsupervisory Personnel: up +0.1% from $20.98 to $21.01, up +1.9%YoY. (Note: you may be reading different information about wages elsewhere. They are citing average wages for all private workers. I use wages for nonsupervisory personnel, to come closer to the situation for ordinary workers.)

The more leading numbers in the report tell us about where the economy is likely to be a few months from now. These were mixed but tilted positive.

- the average manufacturing workweek rose 0.1 hours from 41.6 hours to 41.7 hours. This is one of the 10 components of the LEI and so will affect it positively.

- construction jobs increased.by 6,000. YoY construction jobs are up 231,000.

- manufacturing jobs increased by 15,000, and are up 159,000 YoY.

- Professional and business employment (generally higher-paying jobs) increased by 27,000 and are up 666,000 YoY.

- temporary jobs - a leading indicator for jobs overall - fell by 8,900.

- the number of people unemployed for 5 weeks or less - a better leading indicator than initial jobless claims - rose by 133,000 to 2,488,000, compared with December 2013's low of 2,255,000.

Other important coincident indicators help us paint a more complete picture of the present:

- Overtime was unchanged at 3.4 hours.

- the index of aggregate hours worked in the economy rose sharply by +0.5 from 103.4 to 103.9.

- The broad U-6 unemployment rate, that includes discouraged workers declined - 0.1% from 10.5% to 10.4%.

- the index of aggregate payrolls also rose sharply by 0.8% from 123.1 to 123.9.

- the alternate jobs number contained in the more volatile household survey increased by 101,000 jobs. This represents an increase of 2,439,000 million increase in jobs YoY vs. 2,915,000 in the establishment survey.

- Government jobs rose by 5,000.

- the overall employment to population ratio for all ages 16 and above was unchanged at 59.3% , and has risen by +0.3% YoY. The labor force participation rate was also unchanged at 62.6% and is down -0.3% YoY (remember, this incl udes droves of retiring Boomers).

SUMMARY:

This was a positive report with some mixed signals, but titled towards good news. The bad news was pathetic nomina wage growth, an increase in discouraged workers, a decline inthe E/P ratio in the prime working ages group, and a decrease in temporary help. The good news included the sharp increase in aggregate hours and payrolls, a decrease in the U6 unemployment rate, a decline in those working part time for economic reasons, positive revisions to prior months, and an increase in manufacturing metrics.

An important longer-term note of caution is that this report, even moreso than most this year, significantly underperformed what the near-record population adjusted rate of initial jobless claims predicted. Hiring is lagging firing, and the YoY growth in employment looks increasingly likely to have peaked. That tells me we are in the 6th or 7th inning of thhis expansion. We are beginning to run out of time for significant real and nominal wage growth before the next recession hits, and that means the odds of actual wage deflation in the next recession are starting to increase.

Thursday, August 6, 2015

Why has real median household income declined in the prime working age demographic? It doesn't look like lack of jobs

- by New Deal democrat

Real median household income for those in the prime working age demographic of 25-54 has been in decline on a secular basis since the late 1990s. Why?

Further, when the latest jobs report is released tomorrow, the debate about why wages have been so lagging will inevitably continue. A number of commentators will, incorrectly, point to the decline in real median household income as proof that wages have fallen.

As I have pointed out many times, however, households headed by those of retirement age, 65 or higher, have a median income only a little over half ($35,000) of those of prime working age ($60,000). With the burgeoning number of retiree households, on a secular basis median household income is likely to decline for quite awhile.

But what about prime working age households, those headed by somebody aged 25 -54? As shown in Doug Short's graph, those too have declined from about 1998 through the last year measured, 2013:

As I have already written, a good and more current proxy for this measure is the Employment Cost Index (a median measure), adjusted for inflation, and then further adjusted by the employment-population ratio for ages 25-54:

This gives us a measure current through Q2 2015, that closely approximates the Census Bureau's annual measure.

But that still doesn't entirely resolve the issue. Why has the employment-population ratio of all ages 25-54 gone down on a secular basis since the late 1990s?

One often-mentioned theory is that they are dropping out of the labor force because they can't find work. If so, however, that should be reflected in the measure of those "Not in Labor Force, Want a Job Now."

To test that theory, I ran the following comparison. First, I calculated the number of persons in age group both unemployed and also not in the labor force for age group 25-54. That is the red line in the two graphs immediately below.

Then I calculated what the number would be if we added together the unemployed in that age group, plus a proportionate share of those Not in the Labor Force, but Who Want a Job Now (blue), first normed by population:

and then the same thing normed by the civilian labor force instead of population:

Both measures were set to be equal at their lows of January 2000.

If the primary explanation for the decrease in the employment-population ratio for ages 25-54 were the inability to find a job, the blue line should be at the same level as the red line. In fact, as you can see, it is much lower. That tells us that the primary driver of the increase in persons not being employed in age group 25-54 is not poor job prospects. A likely candidate is that the tradeoff between staying at home to raise children on the one hand vs. employment and the cost of daycare on the other hand, has shifted towards staying at home.

Two important addenda:

1 I estimated those NILFWJN for ages 25-54 from the St. Louis FRED database. FRED does not carry, although the BLS does publish, the specific numbers for those not in the labor force but who want a job now. Here's that graph:

The result, if I were able to integrate that metric into the graphs, would be even more favorable to the conclusion that lack of jobs is not the main culprit in the declining participation of 25-54 year olds. Below are the numbers, in millions, of those NILFWJN in age group 25-54 by the proportional estimate (left), and actually (right), at their lows, peaks, and latest readings:

Jan 2000: 3.509 2.053

Jan 2011 5.373 3.136

Jun 2015 4.659 2.616

If I were able to use the actual numbers in the graphs above, the result would be 1.1 million more favorable to the conclusion.

2. Although they don't count towards the nonemployed in the employment-population ratio, measuring those part time for economic reasons is helpful in determining why real median household income has fallen in the prime working age demographic. Again, this isn't carried by FRED, but it is available at the BLS website, and here it is:

Here are the numbers in millions at their lows, peaks, and latest readings:

Q1 2000 1.342

Q1 2010 4.485 (an increase of about 2% of the labor force)

Q2 2015 2.857 (still about 1% of the labor force above the low)

If we simply figure that the typical part time worker earns about 1/2 of the typical full time worker, for a back of the envelope estimate, that accounts for about 1% of the decline in median household income at its worst, and about 0.5% of any shortfall in median household income for age group 25-54 now.

Tuesday, August 4, 2015

BLS: actually, excluding incentive pay, wages grew at +.6% in both Q1 and Q2

- by New Deal democrat

Worth repeating, from John Jansen at Across the Curve:

"I wanted to make a few observations on the ECI report following our conversation with the BLS.... The sharp deceleration in the growth rate of the wages and salaries component (which accounts for about 70% of total compensation) was driven by a sharp falloff in incentive pay this quarter versus Q1.... Excluding commission sale incentives, wages and salaries were unchanged at a solid 0.6% q/q pace in both quarters."

Wow! So it turns out the poor ECI may not have been poor at all. There were supersized bonuses paid out in Q1 that, seasonably, weren't paid out in Q2.

I just wish the BLS would include crucial information like that in their report, instead of giving it out privately in phone conversations, in this case to a representative of TD Securities, leading to this trading advice by the analyst, which was passed on to Jansen:

"Fade the ECI weakness."

IMO, the public should have been informed of the important unusual factors in the ECI report, so that everybody had it at the same time.

P.S.: I can't vouch for the thirdhand hearsay math in the above quote. Combined wage growth for Q1 and Q2 in the ECI totalled +0.9%. I don't see how we get to +.6% + .6% from there, especially if we back out part of the increase. Just another reason to share the important qualifying information transparently in the report.

P.S.: I can't vouch for the thirdhand hearsay math in the above quote. Combined wage growth for Q1 and Q2 in the ECI totalled +0.9%. I don't see how we get to +.6% + .6% from there, especially if we back out part of the increase. Just another reason to share the important qualifying information transparently in the report.

Monday, August 3, 2015

Working age real median household income (very nerdy)

- by New Deal democrat

After my post yesterday on whether average Americans are better off than in 2008, I had a brief exchange with Doug Short. Doug pointed out that the Census Bureau will be releasing its detailed information next month for 2014 median household income, including by age cohorts. He wrote about this nicely last September, and his post included this graph (through 2013), breaking down median household income by age:

In my article yesterday, I included the following graph as an effort to estimate median household income for the prime working ages of 25 - 54, in which I took inflation-adjusted median wages, and subtracted out the percentage of unemployed:

Upon further reflection, probably a better adjustment is by using the employment-population ratio for ages 25 - 54, which gives me the next graph:

By this measure, median working age household income in 2015 so far has been slightly higher than 2008, although 1% or so under 2007 and before.

Still, looking at Doug's graph above, which shows prime working age household income generally stalled at about 3%-4% under their 2008 levels through 2013, that seems like a lot to ask of one year. But surrounding circumstantial data does suggest that there will be a significant increase in 2014.

First of all, not only did real median wages increase, due mainly to a big decline in gas prices, but the employment-population ratio for ages 25 54 jumped higher in 2014 and so far this year:

Also, as of last August, the National Employment Law Project reported that beginning in late 2013, and even moreso in 2014, job growth accelerated to the point where higher paying jobs were close to 40% of all jobs created.

And Professor Saez's preliminary look at income reported to the IRS in 2014 suggested that the bottom 90% had their best year so far this Millennium, with an increase of about 3.8% (although even that is pitiful compared to the 58% share of income growth taken by the top 1%).

What the Census Bureau will report next month is also affected by how they perform their calculations. Do they compare year-end with year-end? In that case, real income will be higher, since the late-year deflation will be fully reflected. Or will they compare the average over 12 months, with the average over the previous 12 months? In that case, there will be a more modest gain.

I continue to think that adjusting the real median wage by the employment to population ratio for the prime working age group is the best way to estimate working age median household income on a timely basis. So I will go ahead and forecast that the Census Bureau will report a solid gain for that group next month, and we'll see if the forecast pans out.

Why last week's poor median wage report should set your hair on fire about the next recession

- by New Deal democrat

Beginning 3 years ago, I identified poor wage growth as the shortfall in the economy that worries me the most. And it still worries me, even though there has been some modest improvement.

Why? Because unless there is enough of a cushion, the next recession, whenever it comes, there is a significant danger of outright wage deflation. And as we know from the Great Depression, outright wage deflation means that payments on previously contracted debts become, in real terms, higher. This can lead to a vicious spiral of debt-deflation, whereby more and more people fall behind on debt, leading to a further economic contraction, more unemployment, and even more wage deflation, and so the cycle repeats.

Why? Because unless there is enough of a cushion, the next recession, whenever it comes, there is a significant danger of outright wage deflation. And as we know from the Great Depression, outright wage deflation means that payments on previously contracted debts become, in real terms, higher. This can lead to a vicious spiral of debt-deflation, whereby more and more people fall behind on debt, leading to a further economic contraction, more unemployment, and even more wage deflation, and so the cycle repeats.

In the last 7 recessions, beginning in 1970, the median decline in wage growth has been -2.1%. Which means, to have a cushion against wage deflation in the next recession, whenever it comes, we want to start out with nominal YoY wage growth substantially more than 2%. That's where the poor +.2% growth in median wages in the 2nd quarter is important.

First of all, it is important to keep in mind the difference between real, inflation-adjusted numbers and nominal rates. Even with last week's clunker, the YoY trend in real, inflation-adjusted median wages appears to still be positive:

That same positive trend is apparent when we measure by real average hourly wages:

which in the first half of 2015 have been among the best since 1980. The improvement, as I have noted many times, is primarily about the change in the price of Oil.

So the meme that *cyclical* wage growth should improve if the labor market continues to tighten is likely correct, despite the poor ECI report last week.

The problem comes when we examine wages from a very long term, secular viewpoint, in nominal terms. Here's a graph from the Wall Street Journal,

http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-employment-costs-rise-0-2-in-second-quarter-1438345911

showing the nominal quarterly change in median employment costs, going all the way back to 1982:

It is easy to see a declining trend over time, from over +1.5% at the beginning of the 1980s through generally persistent growth of less than +0.5% per quarter beginning during the Great Recession. In other words, over the very long term, quarterly wage changes are moving towards zero.

The same secularly declining trend appears when we measure by average hourly wages, by the way:

This secular deceleration towards zero in nominal wages ought to be setting everybody's hair on fire. There is a world of difference between declining from, say, 4% to 2%, and declining from 1% into outright wage deflation of -1% (or worse), in a recession.

Simply put, we are more at risk for a wage-price deflationary spiral in the next recession than we have been at any point since the 1930s, including being substantially more at risk than we were in 2007.

Sunday, August 2, 2015

Are average Americans better off now than in 2008?

- by New Deal democrat

One of my overarching themes is that the Progressive economic case is inequality, not Armageddon. When the share of income and wealth held by the top 1% and top .01% balloons, the remainder of society stagnates or suffers. But that does't mean that the economy is always and everywhere going to hell for the bottom 99%. Their economic position can be improving during economic expansions - just not enough to overcome the long term pressures on the middle and working class.

I mention this because elsewhere there has been a brief Doomgasm brought about by the poor nominal increase in median wages during the second quarter (about which I'll have more to say in a separate piece). The challenge has been laid down in a political sense, with the refrain, "are people better off than they were in 2008?"

Let's take a look at that using the metrics of wages, income, and wealth.

Wages. When it comes to wages, the answer is pretty clear: as of now, both the average and the median worker are better off than they were in 2008. In fact they are better off, by one measure, than at any point in the last 35 years.

Let's start with the median wage. This is what was reported on Friday to have grown, according to the Employment Cost Index, at the slowest rate in over 30 years (+0.2%), in the second quarter. The St. Louis FRED graph for this data starts in 2001, and here it is in real, inflation-adjusted terms:

As you can see, Q1 and Q2 2005 are the two highest readings in the history of the series. At the same time, consistent with my emphasis on inequality, note that there has only been about 4% growth in real median wages since the beginning of the Millennium.

Now let's look at average hourly income for nonsupervisory workers. This data series goes all the way back to 1964. Here is its entire history, adjusted for inflation:

Again, it is quite clear that real average hourly wages are not just higher in 2015 than they were in 2008, but also higher than at any time since the 1970s. But in terms of inequality, these are still less than 10% better than they were 15 years ago.

Income. Next, what about income, specifically, median household income? Here the story is more complex. The best graphic representation comes from Doug Short, using the monthly updates from Sentier Research:

Here we see that real median household income is less than it was in 2000 or 2007, although it has come back about 2/3 off its low.

But as I have pointed out again and again and again, "income" is not "wages," and households includes the increasing legions of retirees in their 60s, 70s, 80s and even 90s. Typically retirees have income of about only half of the median working household. So the plateau and decline once the advent Boomer generation hit 55 in 2000 should not be a surprise. (The writer of the Doomgasm made this basic mistake, employing a graph of median household income and claiming it showed that wages look really bad since 2007. Wrong. Fundamentally, basically, and completely, wrong).

Since there is no timely report on median household income for working age households, i.e., taking out the burgeoning cohort of retirees, can we make a useful estimate? I believe we can, by taking the unemployment rate into account. Below is a graph of real median wages (again, the subject of the poor report on Friday), adjusted for inflation, and then adjusted for unemployment as well (essentially counting the unemployed as having $0 income, and then subtracting that percentage):

This tells us that median income of all non-retiree households has probably returned to its 2007 levels, and is just below its 2006 peak. But working age median household income has gone essentially nowhere good since the turn of the Millennium.

UUPDATE 8/2/2015: After this post, I had a further exchange with Doug Short, and I took a deeper look at real median household income. I think a better measure is to use the employment-population ratio for ages 25 - 54 rather than the employment rate:

This measure still puts the first half of 2015 slightly ahead of 2008.

Wealth. Finally, let's examine, as best we can, household wealth.

Here the record is particularly scanty. The Census Bureau's last look is from 2011. The University of Michigan performed a study that compared 2013 with 2007. That's the most recent work.

Here is the best write-up I found on the University of Michigan study:

[B]ecause stocks have recovered more quickly than the real estate market—the S&P reached its pre-recession high in March of 2013, while home prices are still far from their 2006 peak—average households were hurt far more than richer Americans when the housing bubble popped. When home equity is excluded from household wealth, the impact of the housing crash on average Americans is especially clear. A median household’s total net worth declined by $42,000 between 2007 and 2013, but their wealth held in non-real estate assets declined by only $6,900.

We have no information at all that take into account the last year and a half. But we do have the Case Shiller house price index, to tell us what has happened with house prices, and here it is:

House prices bottomed at the beginning of 2012. They are up another 10% if we measure from the end of 2013, over 15% if we measure from mid-2013. The median household also holds a small amount of wealth in stocks, usually via 401k's), and those are up 20% since 2013.

We honestly can't really say where household wealth stands now with any exactitude as compered with 2008. What we can say with confidence is that it probably has improved significantly since 2013, and like median working age household income, may have pulled even with 2008.

At the same time, since older households typically have more wealth than younger households, and due to demographics and improved longevity, the population is aging, even the loss of $6,900 in non real estate net worth from 2013 is very troubling. That same University of Michigan study found:

households in the 95th percentile of net worth had 13 times the wealth of the median household in 2003. By 2013, this disparity had increased almost twofold, with the wealthiest 5% of Americans holding 24 times that of the median.

In dollar terms, the median wealth of a US household was $87,992 in 2003, and by 2013 had decreased 36% to $56,335. In contrast, the richest 10% actually saw their net worth increase from 2003 to 2013, with the highest gains going to the top 5%. The median wealth of the households in the top five percent grew over 12% during the same time period, from $1,192,639 to $1,364,834.

So, to summarize:

- measured by average or median wages, the typical working American is better off now than in 2008

- measured by median household income, the typical working age American household is probably also better off than in 2008.

- it is nearly impossible to know the current status of median household wealth, but it has probably improved since 2013, and may have pulled even with 2008.

At the same time, the continued and rising inequality of wages, income, and wealth, is simply staggering. Measured since the beginning of the Millennium, the median wage-earner or household is just treading water, while the top 1% and top .01% have seen their financial assets skyrocket. That is not the American Dream.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)