Saturday, November 15, 2014

Weekly Indicators for November 10 - 14 at XE.com

- by New Deal democrat

My Weekly Indicators piece is up at XE.com.

More softness has shown up in coincident indicators.

US Equity Market Review For the Week of November 17-21

One month ago, traders had re-examined their risk calculus and determined that equities were too risky, sending shares lower and the vix higher. A rally in the bond market was reaching its apex, equities sold off and momentum indicators cratered to some of the lowest levels in years. Fast forward a mere month, and the entire environment has more or less changed: equities have returned to previous levels, momentum indicators are back at higher levels and the vix is again showing market calm.

Nothing highlights this changing situation more than the Vix, which spiked in mid-October to 26.25 but which has returned to a far more tranquil reading of 13.3. And note the speed with which things have settled down; in less than a month, the market has gone from about a week of "holy shit, everything is changing" to "we're back to where we were."

The 30 minute charts of the SPY and IEFs highlight this change.

Nothing highlights this changing situation more than the Vix, which spiked in mid-October to 26.25 but which has returned to a far more tranquil reading of 13.3. And note the speed with which things have settled down; in less than a month, the market has gone from about a week of "holy shit, everything is changing" to "we're back to where we were."

The 30 minute charts of the SPY and IEFs highlight this change.

Over the last month, the SPYs have slowed and consistently moved higher. The rally has consolidated gains on several occasions and, after doing so, resumed its ascent. However, the pace of the rise has clearly decreased, with prices forming a slow yet very price obvious arc.

At the same time, the bond market has not sold off to the same degree as the equities rally. Instead, the IEFs have consolidated their position between the 104.5 and 105.25 price levels since the end of October. If traders were seriously re-allocating their portfolios due to a return of the "equities are going to continue rallying" concept, we'd see bonds move lower. But that isn't happening.

In fact, the weekly TLTs (20+ section of the curve) are still obviously in an uptrend. All the EMA -- short and long -- are moving higher. The only bearish element on this chart is the decline in volume over the last few weeks, which could indicate the trend is about to reverse. But prices would need to move at least another 2% lower, which is a far larger bond market than equity market move.

That leads to the question: what's next? To answer that, let's look at the daily chart of the micro, mid and large cap ETFs:

The large caps' chart (OEF, top chart) is most closely tracking the SPYs. Prices have moved through previous resistance, although the pace of the rally has clearly decreased, indicating short-term declining momentum. In contrast, the mid-caps (middle chart) haven't made new highs, instead resting right at previously attained levels. And while the micro-caps (bottom chart) have broken through resistance levels, they clearly have little upward momentum.

This means that overall, we have a potential for another 5%-10% rally caused by events like a solid GDP read or strong employment report. But ultimately the market is still expensive, requiring positive fundamental news to move higher. It also makes this a stock-pickers market were a company that is growing faster than the economy as a whole and its sector and then its industry will fetch a premium price.

Friday, November 14, 2014

Gas price declines power consumers in October

- by New Deal democrat

I have a new post up at XE.com on this morning's retail sales number.

This is our first indication of how much the decline in gas prices is helping out consumers.

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Jobs and wages graphapalooza!

- by New Deal democrat

At the end of the day, the economy ought to operate to bring the most benefit to the most people. Jobs and wages are a pretty good proxy for that desideratum. With that in mind, let me update some of my graphs about them.

At the end of last year, Congress cut off extended unemployment benefits, on the theory that they provided a "hammock" for the unemployed, who would otherwise be motivated to find new jobs. If that's true, then those who told the Census Bureau that they were not even looking anymore, and so were out of the labor force, but wanted a job now, should be declining. Here's what has actually happened (graph shows NILFWJN as percent of work force):

Instead of falling, nearly a million more people, or .4% of the workforce, have been added to this group. Aside from the privation, and aside from the fact that these people aren't adding to the economy by spending the benefits, that means that unemployment is 0.4% lower than it would otherwise be.

Another way to look at the overall employment situation is to look at how many hours of work are available to those in the labor force, and those who want a job now but aren't counted in the work force:

This continues to slowly increase and is only about 1.8% below its 2007 peak and 5.8% below its peak during the 1990s tech boom.

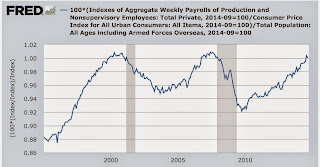

How about wages? One measure I like is how much total real wages are available per person in the US population. That's what is shown in this next graph:

In the aggregate, real wages are quite close to their prior peaks. That tells us that it is the distribution of income among the workforce that is the most acute problem.

Finally, even back in the horrible days of 2008 and 2009 I used to like to find at least one item of good news. That's the final graph, showing something that went totally unremarked in last week's employment report. Namely, we have passed the 10,000,000 mark in new jobs added to the economy since the jobs trough in February 2010:

Once upon a time, Doomers used to claim that we weren't really adding any jobs, or were just "bottom bouncing." They went silent on that claim quite a while ago. Then they claimed that the jobs recovery was only part time jobs. Part time jobs are that nearly flat line at 0 at the bottom. 99% of all of the jobs added have been full time jobs.

Except for the vile conduct of Congress a year ago in cutting off extended unemployment benefits, we are still making progress. Not nearly enough, not nearly what I would like to see, but nevertheless progress.

The mighty Krgthulu has spoken: median income =/= median wages

- by New Deal democrat

I've called median household income The most misused statstic in the econoblogosphere. People routinely cite it to claim that wages have fallen since the onset of the Great Recession. They have not.

The "households" included in the statistic include all those headed by anyone over age 16, including the burgeoning cohort of elderly retirees. Even excluding that age cohort, it includes households including the unemployed. Strip out the elderly and adjust for unemployment, and household incomes show the same stagnation as wages.

But now the authoritative voice of Krgthulu Has spoken

although Leonhardt talks about wages, the chart he shows is median income, which is a somewhat different story. Wages for ordinary workers have in fact been stagnant since the 1970s, very much including the Reagan years, with the only major break during part of the Clinton boom.I hereby invoke Delong's Rule:

QED1. Paul Krugman Is Right. 2. If You Think Paul Krugman Is Wrong, Refer to #1

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Making the case that the consumer is slowing down

- by New Deal democrat

A year ago, based on the long leading indicators at the time, I thought the economy would be in the midst of a slowdown about now. I have a new post up at XE.com, making the Case for a consumer slowdown, based on trends in housing and cars.

The evidence is far from solid, especially given the relief consumers are having at the gas pump. We'll see.

It's (also) the interest rates, stupid!

You know the old saw, "it's the economy, stupid!" Both Robert Reich and Atrios have boiled last week's election results down to that maxim.

Atrios said, "It isn't really a big mystery why people still aren't thrilled with the economy. The foreclosure crisis and the great recession destroyed lives, and opportunities for The Kids Today are pretty crap."

Reich blames median household income:

If you want a single reason for why Democrats lost big on Election Day 2014 it’s this: Median household income continues to drop.This is the first “recovery” in memory when this has happened.Jobs are coming back but wages aren’t.While I agree with his prescription:

[Democrats] have a choice.

I disagree about using the metric of median household income, since your 75 year old Uncle Earl and 85 year old grandma are counted in that statistic, and there are a ton more Uncle Earls and Grandmas than there used to be (more on that below); and among 25 to 54 year olds it tracks the employment to population ratio nicely.They can refill their campaign coffers for 2016 by trying to raise even more money from big corporations, Wall Street, and wealthy individuals.And hold their tongues about the economic slide of the majority, and the drowning of our democracy. Or they can come out swinging.

While the lack of a platform that speaks to younger voters was certainly an issue, I believe almost all commentators have overlooked another crucial component of what happened last week -- interest rates.

You've probably seen this graphic already from ABC news, showing the skew among age groups over the last 5 elections. Note that younger voters constituted 12% of the electorate in each of that last 3 midterms.

But look at what happened with the 60+ cohort: it grew from 23% in 2006 to 32% in 2010, to 37% in 2014!

Not only has the midterm electorate skewed heavily towards senior citizens in the last 8 years, but the senior citizen cohort itself has become more conservative. The reason? Most people arrive at their basic political orientation at about age 18, and never fundamentally change. In 2006, 65 year olds had turned 18 in 1959. In 2010, that was 1963. This year it was 1967.

Now let's look at how 18 year olds political orientation has changed over time:

In 2006, there were still some FDR era voters around. By yesterday, they had all but disappeared, replaced by an island of JFK era 18 year old blue voters amidst a red tide of Truman, Eisenhower, and LBJ voters. In other words, the 65+ year old cohort that went to the polls in 2014 was the most conservative in several decades. (PS: Note that Obama turned 18 in very red 1979, which might not be a coincidence with his apparent veneration for Reagan).

And what do elderly voters care about? It isn't jobs, and it isn't wages. After all, they are almost all retired!

No, what they care about is the interest rates their CD's and money market accounts are earning, and the COLA adjustments to their Social Security.

And there, the news has been abysmal for the last 6 years.

Here's the rate on CD's from 2008 to the present:

And here's the COLA adjustment to Social Security in the last 6 years:

Average CD rates have run no higher than 1%. Social Security COLA has averaged 2.2%.

Now here's inflation (and keep in mind that there is evidence that seniors probably face higher inflation rates for what they buy):

For the last 5 years, inflation has averaged about 2% a year.

Obama and the democrats are seen as having bailed out Wall Street in 2009. Meanwhile savers and those on fixed incomes have taken it in the chops.

So let's review:

- A burgeoning midterm electoral cohort

- skewing more conservative than in several decades

- that is the prime viewership for Fox News

- took it in the chops on their savings and, to a lesser extent, Social Security.

- They blamed Obama and the democrats.

Last week, they got even.

Sunday, November 9, 2014

A thought for Sunday: the importance of state-level third parties

- by New Deal democrat

[You know the drill. It's Sunday. Regular nerdy economic blogging will resume tomorrow. And be sure to read Bonddad's latest summary, below]

There was a devastating piece about the Democratic Party published about a month ago by Chris Bowers, I think, that reads particularly bitterly in the light of last Tuesday's midterm election results. Of course I can't find it now. (UPDATE: I think it was This piece. By Matt Stoller. If you haven't read it yet, go read it now). But in summary, it said that the high point of the left netroots was the Lamont-Lieberman Senate contest in 2006. Anti-Iraq war progressives defeated Joe Lieberman in the primary. But because Connecticut has no "sore loser" law preventing primary losers from re-filing and running as independents in the general election, Lieberman did so, and the Democratic Party establishment, including one Barack Obama, rallied around him. When Lieberman won with the help of GOP votes, he got a standing ovation in the Senate.

In 2008 most of the netroots backed Obama, who also suggested that he was anti-Iraq war (he never actually cast a vote) vs. the pro-Iraq war Hillary Clinton. But once Obama won and no longer needed progressives, he dumped Howard Dean as Democratic Party Chair, along with his "50 state strategy," and installed economic neoliberals as his most powerful appointments.

The point Bowers(?) was making is that the party establishment learned in 2006 that it didn't have to worry about progressives. Progressives would lose most primaries where the primary determinant was money, and then they would fall meekly in line, backing a centrist Democrat in the general. This is where Kos's mantra "more and better" democrats led.

The GOP, when installed in power via Bush, or even with a stranglehold on a necessary artery, like the filibuster rule in the Senate, has relentlessly pursued a maximalist strategy, rallying round the most extreme policies and maybe compromising a little at the end. The democratic estabslishment, with no party discipline to the right, pursues milquetoast centrist policies and even then compromises with the GOP.

The Progressive voice is never going to be heard, let alone come to power, under these circumstances.

In order to do so, progressives need to take a page from the historical rise of the UK's Labour Party. One hundred years ago, the UK's two major parties were the Conservatives (a thoroughly reactionary party), and the Liberals, a center-left coalition much like today's Democrats. The Labour Party formed after the Liberals stabbed them in the back.

And Labour did not win by defeating Conservatives. Labour won by driving the Liberal party to the brink of extinction.

Similarly, progressives will not win because of GOP losses. Progressives will only win by driving corporatist democrats to the edge of extinction, just as movement conservatives took over the GOP by making Rockefeller Republicans as extinct as the dodo bird).

As spelled out above, corporatists are throughly in charge of the democratic establishment, to the point, it is widely reported, that they would prefer GOP election wins over progressive democratic candidates. See, for example, here

So, how to make corporatist democrats extinct? By showing them that they can never win. And how do you show them that they will never win? By borrowing a page from the career of Joe Lieberman.

It isn't enough for progressives to primary corporatists. State level third parties, like New York's Green Party, give progressives the ability to stay in elections right through the general election, even if they lose a democratic primary to corporatists.

Yes, this strategy will mean some general election losses over a few cycles. But when corporatist democrats learn that they cannot win, they will start to disappear. Progressives will win either as Democrats, or under another party banner.

By the way, this happened before. One hundred years ago, there were active Populist and Progressive Parties in the states (remember Robert LaFollette?). Ultimately they became part of the winning New Deal coalition.

Progressives shouldn't abandon the Democratic Party. But they should target the corporatists as mercilessly as Tea Party republicans targeted their less-extremist wing, and state level Third Parties are an indispensable part of that attack.

US Equity Market Summary For The Week of November 3-7

At the end of last week's column, I make the following observation:

So, in conclusion, we're where we were a few weeks ago: a market that is pretty expensive that has decent earnings growth potential but whose various companies also face some a weak international environment and a stronger dollar. That limits the upside potential a bit.

To begin this week's market review, let's take a look at the overall valuation of the major indexes:

The above screen shot from the WSJ's market page highlights the bulls predicament. The S&P 500 is trading at a PE of 19; this isn't "super" expensive, but it certainly isn't cheap either. And its forward PE of 16.65 doesn't provide a great deal of upside room. The NASDAQ 100 has the same problem; it's currently more expensive than the S&P 500 and its forward PE is also high, limiting a rally. The Dow is in a somewhat better position, but, frankly, as an index it's an historical anachronism -- I follow it because I have to, bit because it provides a unique insight into the markets.

And not only are the valuation measures limiting a potential rally, so is increased international economic risk. The EU is hovering just above recession and/or a deflationary situation, Russia is quickly becoming a potential economic disaster, Abenomics is stalling and China's real estate market is starting to fall under its own weight. Although the US economy is actually on decent footing, most major companies derive a fair amount of their revenue from international operations. This means the potential international slowdown has negative implications for earnings growth, and, by extension, a potential market rally. And, just to add the icing on the cake, the dollar is rallying, making the repatriation of profits that much more difficult. All of the previously listed issues add up to limit any rally.

The limited upside potential is highlighted on the SPY daily chart. In mid-October, the market had a sharp sell-off from peak to trough of 201.9 to 181.92 -- a near 10% selloff. But nearly three weeks later, prices rebounded, erasing losses and eventually making new highs. The pace of the rally, however, has decreased. Note in the circled area the candles have narrower bodies, indicating the opening and closing levels for that trading day were very close. Overall volume has also decreased.

The micro-caps (daily chart above) hit resistance at their upside resistance trend line. More importantly, they didn't continue through resistance with the other averages.

So, in conclusion, we're where we were a few weeks ago: a market that is pretty expensive that has decent earnings growth potential but whose various companies also face some a weak international environment and a stronger dollar. That limits the upside potential a bit.

To begin this week's market review, let's take a look at the overall valuation of the major indexes:

The above screen shot from the WSJ's market page highlights the bulls predicament. The S&P 500 is trading at a PE of 19; this isn't "super" expensive, but it certainly isn't cheap either. And its forward PE of 16.65 doesn't provide a great deal of upside room. The NASDAQ 100 has the same problem; it's currently more expensive than the S&P 500 and its forward PE is also high, limiting a rally. The Dow is in a somewhat better position, but, frankly, as an index it's an historical anachronism -- I follow it because I have to, bit because it provides a unique insight into the markets.

And not only are the valuation measures limiting a potential rally, so is increased international economic risk. The EU is hovering just above recession and/or a deflationary situation, Russia is quickly becoming a potential economic disaster, Abenomics is stalling and China's real estate market is starting to fall under its own weight. Although the US economy is actually on decent footing, most major companies derive a fair amount of their revenue from international operations. This means the potential international slowdown has negative implications for earnings growth, and, by extension, a potential market rally. And, just to add the icing on the cake, the dollar is rallying, making the repatriation of profits that much more difficult. All of the previously listed issues add up to limit any rally.

The limited upside potential is highlighted on the SPY daily chart. In mid-October, the market had a sharp sell-off from peak to trough of 201.9 to 181.92 -- a near 10% selloff. But nearly three weeks later, prices rebounded, erasing losses and eventually making new highs. The pace of the rally, however, has decreased. Note in the circled area the candles have narrower bodies, indicating the opening and closing levels for that trading day were very close. Overall volume has also decreased.

The 30 minute chart adds more detail to the analysis. There are two rallies. The first starts mid-way through the 15th, continues through resistance until November 4th and then breaks the trend. The second rally started on the 4th, but has a lower angle, indicating declining momentum.

Two other broad indexes raise concerns about a potential continuation of the rally: the IWCs and QQQs.

The micro-caps (daily chart above) hit resistance at their upside resistance trend line. More importantly, they didn't continue through resistance with the other averages.

And while the QQQs broke through resistance, they traded sideways last week, which is better seen on the 5-minute chart:

The detailed daily chart shows the QQQs hit resistance at the 101.6-101.7 level and failed to continue higher. In fact, last week's QQQ 5-minute chart looks like a sideways consolidation pattern.

Last week's sector performance chart also shows why the overall advance was subdued. While industrials and financials advanced, so did utilities, health care and staples -- three sectors that are defensive in orientation.

And when we look at year-to-date sector performance, defensive sectors again are the two top performers also representing 3 of the top 4.

To return to the theme from the opening paragraph, the market is expensive and faces moderately strong headwinds in the form of increasing international economic uncertainty and a stronger dollar. When these factors are combined with the more defensive nature of the market's advance and its already expensive valuation levels, a topside rally is limited, barring better company or sector level earnings news and/or speculation. That makes the current more and more a stock-pickers market.

Last week's sector performance chart also shows why the overall advance was subdued. While industrials and financials advanced, so did utilities, health care and staples -- three sectors that are defensive in orientation.

And when we look at year-to-date sector performance, defensive sectors again are the two top performers also representing 3 of the top 4.

To return to the theme from the opening paragraph, the market is expensive and faces moderately strong headwinds in the form of increasing international economic uncertainty and a stronger dollar. When these factors are combined with the more defensive nature of the market's advance and its already expensive valuation levels, a topside rally is limited, barring better company or sector level earnings news and/or speculation. That makes the current more and more a stock-pickers market.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)