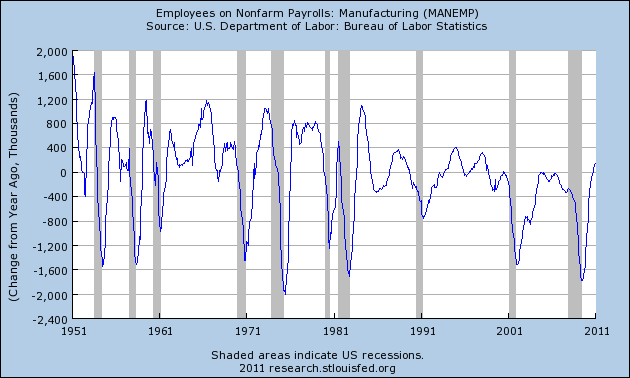

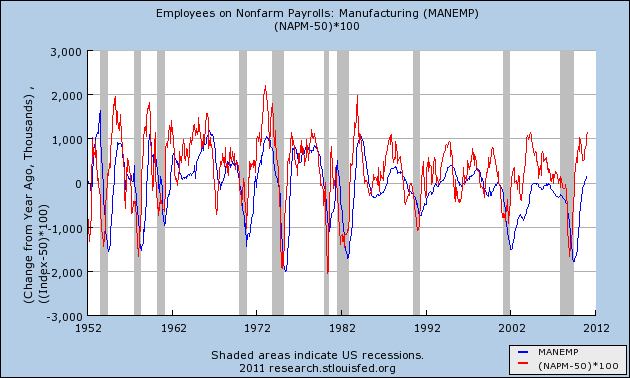

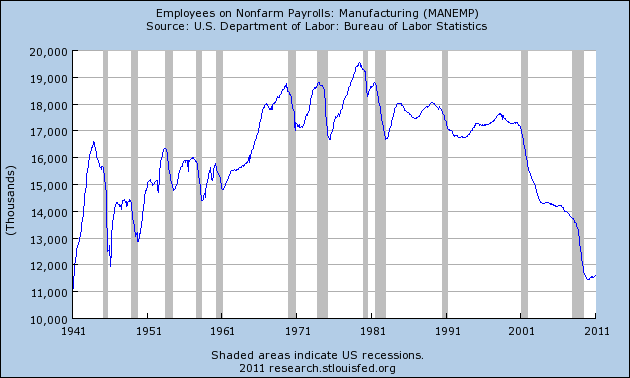

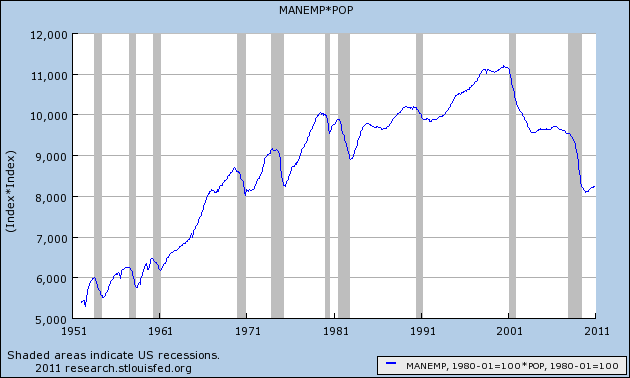

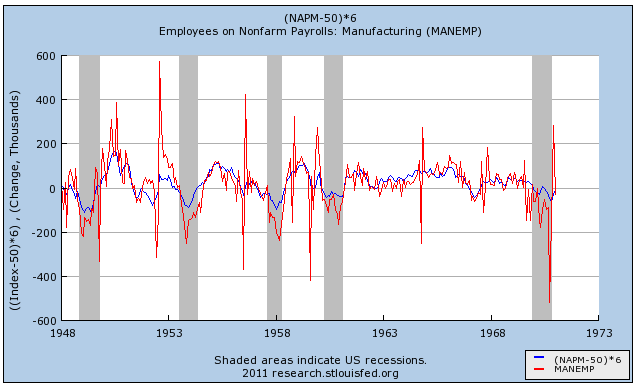

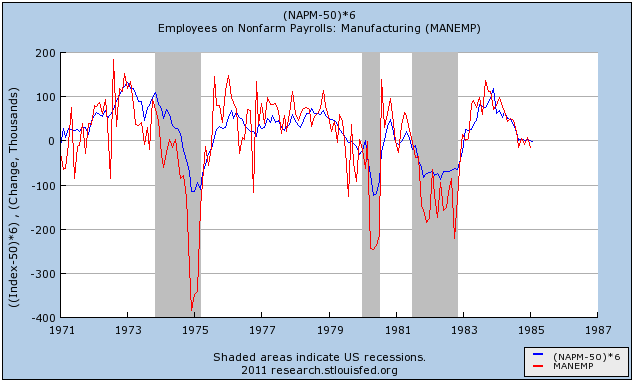

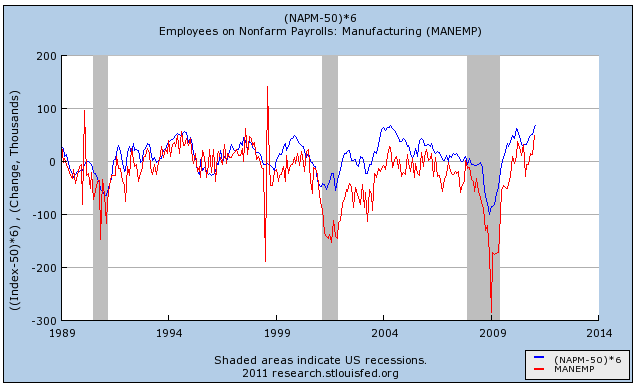

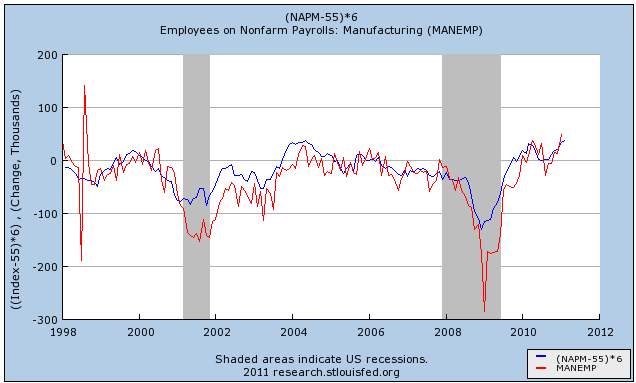

The monthly data this past week was all about income and jobs. The economy added 192,000 jobs in February, and both December and January were revised higher. This marks the 12th time in the last 13 months that the initial report for the prior month was revised higher. This is a sign of a self-sustaining recovery. The unemployment rate, against expectations, dropped another 0.1% to 8.9%. As I'll discuss on Monday, the drop in the unemployment rate could be the real surprise economic story of 2011. Both of the ISM indexes also showed increased expansion. Non manufacturing came close to equaling its best reading in 10 years, and the manufacturing reading was last exceeded almost 30 years ago, in 1983. Even so, only +33,000 manufacturing jobs were added. (BTW, I have discovered that I made an error in a post I wrote this week. I used the ISM employment index rather than the overall ISM index to calculate how this month would fit with the past. The correct calculation would have predicted +27,000 manufacturing jobs vs. +57,000 manufacturing jobs).

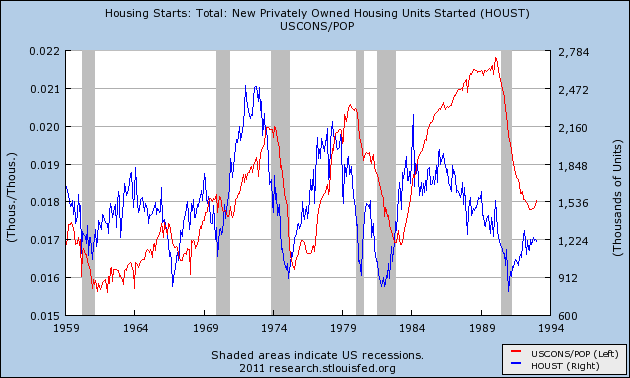

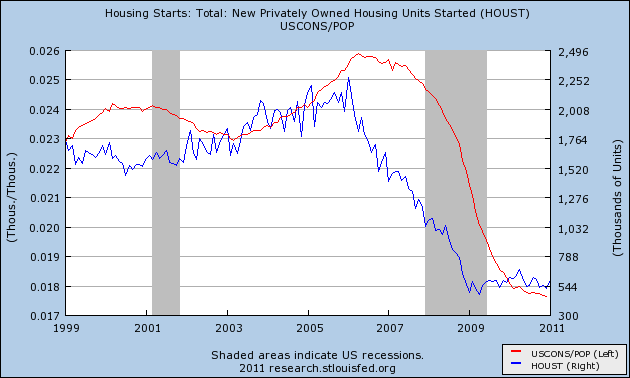

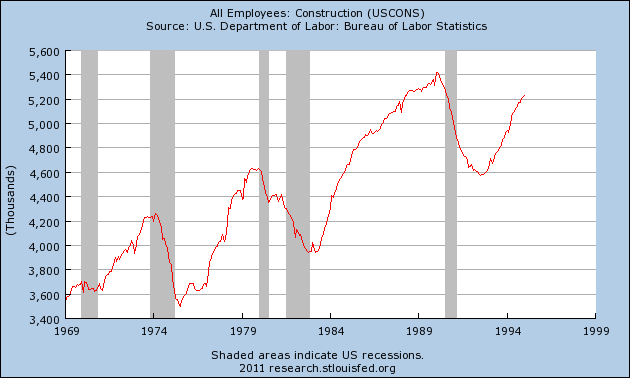

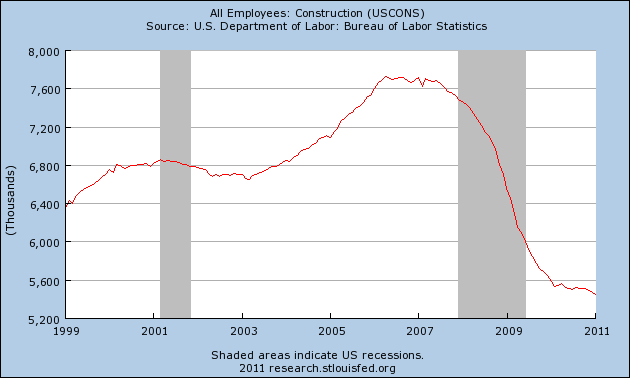

Meanwhile, personal spending rose a little, although not as much as inflation. Personal income rose over 1%, but only because of the withholding tax rebate. This is the equivalent of trying to feed the village some of its seed corn. Thankfully, for the moment the villagers are saving it. January factory orders were also up, and December was revised higher. Residential and nonresidential construction both remained flat on their backs.

Leading Indicators for February will be interesting, but will probably be up (the current forecast is +0.9). Initial claims were down strongly, and the manufacturing workweek increased, as did the ISM vendor delivery reading, and consumer expectations for the future. Interest rates and the stock market remained positive. But there was a significant decline in core capital goods spending, and we don't know what will ultimately happen with real MoM money supply, consumer nondurable new orders, and housing permits.

As you know, I am watching our high frequency indicators now especially to contrast the forces of continued strengthening against Oil's choke hold on the economy. In the last two weeks, both series have spiked past their inflection points.

The BLS reported that Initial jobless claims came in at 368,000. The 4 week average is 388,500. These are the lowest readings since July 2008.

Oil jumped another $7 to $104.42 a barrel. This is a 15%+ move in only two weeks, and qualifies as a price shock at this point. It is also about $10 over the point where it will sop up 4% of GDP. There WILL be a significant economic slowdown, the only questions is how much and for how long. Gas at the pump rose almost twenty cents in one week to $3.39 a gallon. This is an increase of $.70 in just over 4 months. Despite that, this week gasoline usage was almost 300,000 barrels a day higher than last year, or +3%. This may be an outlier since this week last year was unusually low compared with surrounding weeks. I expect this comparison to deteriorate if the oil price spike continues.

Railfax stabilized at up 4.4% YoY. Baseline and motor vehicle carrier traffic still remain barely ahead of last year on a 4 week moving average, and shipments of waste and scrap metal remain at last year's levels. Intermodal traffic, a gauge of imports, was up 7.2% YoY.

The Mortgage Bankers' Association reported a decrease of 6.5% in seasonally adjusted mortgage applications last week, canceling out last week's increase. This series continues to meander generally in a flat range since last June. Refinancing also decreased 6.5%, and also remains near its lowest point since last July 3. This is not an auspicious start to Spring selling season.

The American Staffing Association Index remained at 90 for the 4th week in a row. This series has completely stalled out in terms of relative YoY gains. In other words, it has stopped making progress towards its pre-recession peak, although it remains 7% ahead of where it was a year ago.

The ICSC reported that same store sales for the week of February 26 increased 3.3% YoY, and also increased 0.5% week over week. This series' YoY comparisons had been trending lower since the first of the year, but for the last two weeks there have been good YoY comparisons. Shoppertrak reported that sales rose a whopping 11.4% YoY for the week ending February 26. It attributed this to the change in the week of President's Day this year vs. last year. On a week over week basis, sales increased 0.1%.

Weekly BAA commercial bond rates dropped -.09% more, to 6.06%. This compares with a -.14% decrease in the yields of 10 year treasuries to 3.46%. Both series are declining from recent highs, and there is still no relative weakness in corporate bonds.

M1 was up 1.4% w/w, up 1.1% M/M, and still up a strong 10.1% YoY, so Real M1 is up 8.4%. M2 was up 0.1% w/w, up .6% M/M and up 4.3% YoY, so Real M2 is up 2.6%. M2 is back above 2.5%. There has never been a recession with real M1 and M2 at these levels.

Adjusting +1.07% due to the recent tax compromise, the Daily Treasury Statement showed that March started out poorly, as the first 3 days showed $27.2 B vs. $36.5 B a year ago, for a loss of -9.3 B YoY. For the last 20 days, $149.7 B was collected vs. $149.3 B a year ago, for a paltry gain of $0.4 B. The month of February, however, finished at $146.4 B vs. $139.6 B last year for a gain of $6.8 B. I suggest using this series with extra caution, because while we might be seeing a real slowdown in tax receipts collected, it may just be that the adjustment for the withholding tax compromise is incorrect - or it may be some of both.

Oil jumped another $7 to $104.42 a barrel. This is a 15%+ move in only two weeks, and qualifies as a price shock at this point. It is also about $10 over the point where it will sop up 4% of GDP. There WILL be a significant economic slowdown, the only questions is how much and for how long. Gas at the pump rose almost twenty cents in one week to $3.39 a gallon. This is an increase of $.70 in just over 4 months. Despite that, this week gasoline usage was almost 300,000 barrels a day higher than last year, or +3%. This may be an outlier since this week last year was unusually low compared with surrounding weeks. I expect this comparison to deteriorate if the oil price spike continues.

Railfax stabilized at up 4.4% YoY. Baseline and motor vehicle carrier traffic still remain barely ahead of last year on a 4 week moving average, and shipments of waste and scrap metal remain at last year's levels. Intermodal traffic, a gauge of imports, was up 7.2% YoY.

The Mortgage Bankers' Association reported a decrease of 6.5% in seasonally adjusted mortgage applications last week, canceling out last week's increase. This series continues to meander generally in a flat range since last June. Refinancing also decreased 6.5%, and also remains near its lowest point since last July 3. This is not an auspicious start to Spring selling season.

The American Staffing Association Index remained at 90 for the 4th week in a row. This series has completely stalled out in terms of relative YoY gains. In other words, it has stopped making progress towards its pre-recession peak, although it remains 7% ahead of where it was a year ago.

The ICSC reported that same store sales for the week of February 26 increased 3.3% YoY, and also increased 0.5% week over week. This series' YoY comparisons had been trending lower since the first of the year, but for the last two weeks there have been good YoY comparisons. Shoppertrak reported that sales rose a whopping 11.4% YoY for the week ending February 26. It attributed this to the change in the week of President's Day this year vs. last year. On a week over week basis, sales increased 0.1%.

Weekly BAA commercial bond rates dropped -.09% more, to 6.06%. This compares with a -.14% decrease in the yields of 10 year treasuries to 3.46%. Both series are declining from recent highs, and there is still no relative weakness in corporate bonds.

M1 was up 1.4% w/w, up 1.1% M/M, and still up a strong 10.1% YoY, so Real M1 is up 8.4%. M2 was up 0.1% w/w, up .6% M/M and up 4.3% YoY, so Real M2 is up 2.6%. M2 is back above 2.5%. There has never been a recession with real M1 and M2 at these levels.

Adjusting +1.07% due to the recent tax compromise, the Daily Treasury Statement showed that March started out poorly, as the first 3 days showed $27.2 B vs. $36.5 B a year ago, for a loss of -9.3 B YoY. For the last 20 days, $149.7 B was collected vs. $149.3 B a year ago, for a paltry gain of $0.4 B. The month of February, however, finished at $146.4 B vs. $139.6 B last year for a gain of $6.8 B. I suggest using this series with extra caution, because while we might be seeing a real slowdown in tax receipts collected, it may just be that the adjustment for the withholding tax compromise is incorrect - or it may be some of both.

So the leading data still looks positive, the monthly coincident data is strong, and the lagging data - the unemployment rate in particular - continues to improve. But Oil remains the 800 pound gorilla in the room, and I believe the weekly indicators, ex-jobless claims, for the last month show that it is already having an impact.

Finally, to help you understand why both of us have such a strong reaction to people who denigrate or ignore data which inconveniently conflicts with their pre-existing political narrative, I give you the following photograph of Bonddad and New Deal democrat relaxing together over a weekend:

Pardon me while I go look for my slide rule. Have a nice weekend!