- by New Deal democrat

Consumer inflation in December continued to be a tale of the relative importance of gas prices vs. the lagged effect of home prices.

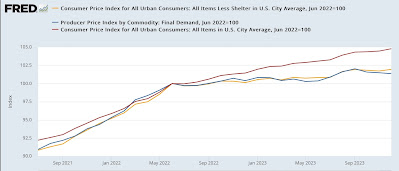

Headline inflation increased 0.3%, and was up 3.4% YoY. YoY headline inflation has bounced between 3.1%-3.7% for the past 6 months, i.e., ever since the gas price peak of June 2022 passed out of the YoY comparisons. “Core” inflation ex-food and energy also increased 0.3%, and was up 3.9% YoY, the lowest YoY increase since May 2021. Inflation ex-shelter rose 0.2%, and is only up 1.9% YoY (originally I wrote there was a monthly decline of -0.4%. That was in error. Not sure where that came from!):

Here are the YoY% comparisons for each:

And to demonstrate the importance of the peak in gas prices in June 2022, as well as the lagged effect of house prices, here is the % change in each since then:

Headline inflation is up 4.8% in the past 18 months, while core inflation, which does not include energy, is up 6.5%. But inflation ex-shelter is only up a total of 0.2% since then!

Once again, for all intents and purposes, consumer inflation for the past year and a half has been all about house and apartment prices (and the measurement thereof).

As to shelter, here is the update to my graph of the YoY% change in house prices, as measured by the FHFA, vs. Owners Equivalent Rent in the CPI:

The YoY% change in OER declined -0.2% to 6.5% in December, the lowest YoY change since August 2022. It will likely continue to decline at the same slow pace in the next few months. (As an aside, I shouldn’t have to say this, but I didn’t just start citing this when I expected OER to come down. I’ve been pounding on this theme since late 2021, when I expected the lagged effect of house prices to drag OER higher - indeed to 8% or more. Which it did.)

The former problem areas of new (red) and used (blue) car prices continue to cool, as the supply bottleneck for new cars and their components has eased. New car prices increased 0.3% in December, and are *down* -1.3% YoY. Used car prices increased 0.5%, reversing a declined from the previous month, and are up only 1.0% YoY. Below I show them normed to 100 as of just before the pandemic hit, and compare with average hourly wages for nonsupervisory workers (gold):

Wages have actually increased 1.3% higher than new car prices since February 2020, while used car prices, up 38.1% since then, are still about 16% higher than comparable wage growth. As a result I expect continued downward pressure on those.

The biggest current problem area is the related sector of transportation services, which includes car repairs and insurance. These only increased 0.1% in December, but remain higher by 9.5% YoY:

This has partly to do with a shortage of repair parts, and partly because vehicle owners responded to higher car prices by holding on to their older cars, which have required increasing repairs. I have also heard that there has been consolidation in the repair industry, leading to some oligopolistic price increases. Additionally, motor vehicle insurance has necessarily also increased in cost.

A second recent problem area has been food away from home, i.e., restaurants. These prices increased 0.3% in December and are higher by 5.2% YoY:

This also seems to be an issue where we can expect further downward pressure.

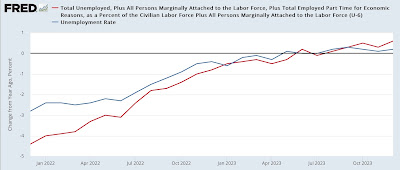

Finally, let’s update real aggregate nonsupervisory payrolls, an excellent indicator of the state of purchasing power. Since payrolls increased 0.2% in December, the net effect was a decline of -0.1% in this metric from its November all time high:

But it is still up 2.4% YoY. As you can appreciate, this is well within the range of noise and would only be of concern if no further progress is made.

So in summary, with the big decline in gas prices over for the moment, for all intents and purposes consumer inflation remains all about the lagged effect of house prices on the measure of shelter, which accounts for 33% of headline inflation and 40% of core inflation. We can expect that to continue to decline slowly in the months ahead, so the issue is going to be what happens with energy in particular over that time. The only negative I see is that YoY wage growth is likely to continue to decelerate, so if headline inflation remains reasonably constant, real aggregate payroll growth will probably continue to decelerate, and may stall out.