See you on Monday.

Five major indexes have all commenced a primary up-trend, signaling the start of a bull market. A word of caution: the recovery is exceedingly fragile. I will only feel comfortable with the bull signal when the Fed and other central banks start raising interest rates. And that is unlikely to occur for some time — without risking a second contraction. Keep your guard up — and your stops tight.

Your crooked friends in Washington and in the Goldman Sachs building are the only reasons for this rally. Maybe the market won't collapse until Q3 earnings start coming out, and until then you will keep snickering. But my faith that:

1. The truth about the economy will, sooner or later, emerge;

2. Like prayers, technical analysis may be "delayed, but not denied" in its projections

3. The fortitude of those strong enough to stick by their intellect-based conclusions will, in the end, win the day, even if the bullies and fraudsters managed to fool the public for a while longer.

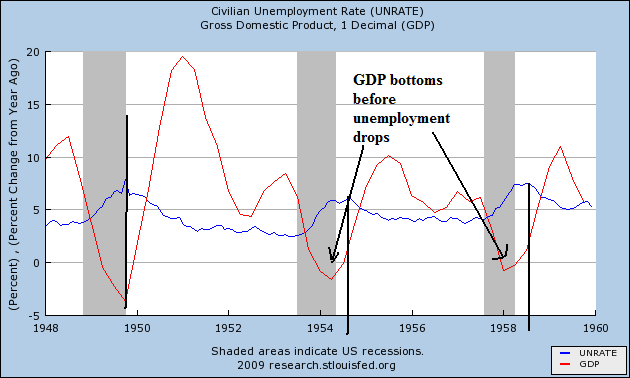

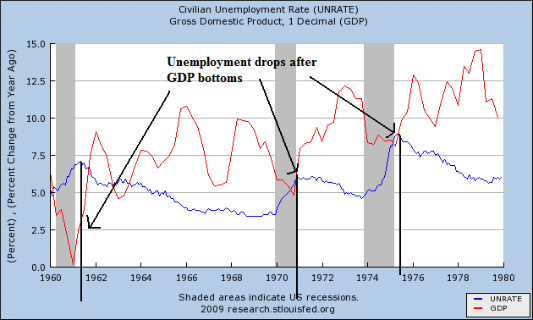

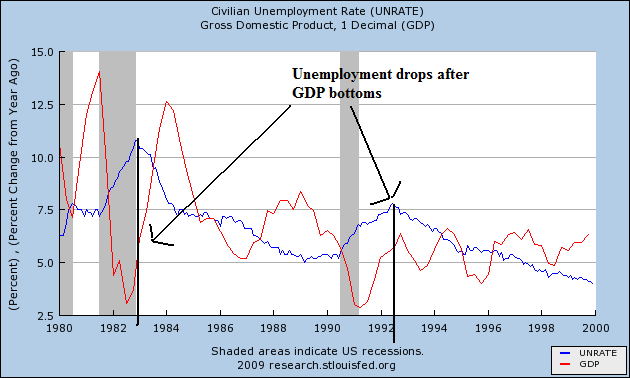

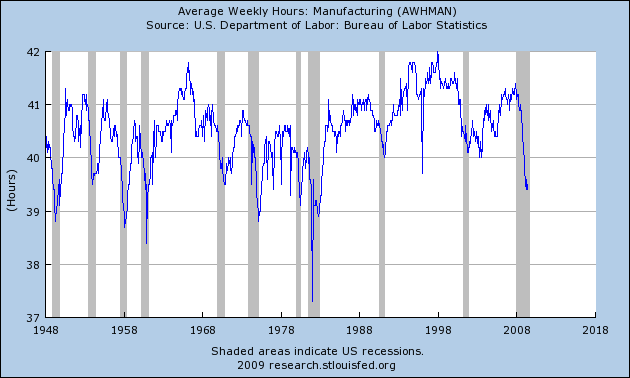

Though today's disparity between growth and jobs is especially stark, a jobless recovery wouldn't be new: The past two recessions were marked by firms reluctant to resume hiring right away after demand recovered. The current disconnect could reflect an unanticipated surge in productivity -- companies finding ways to increase output with fewer workers. That could set up the economy to grow rapidly in future years. Rising productivity is the linchpin of economic growth and rising living standards.

But there are darker scenarios. Struggling workers, whose wages also are being squeezed, could drag a fragile economy back into deep recession.

"Final demand and production have shown tentative signs of stabilization," Mr. Bernanke told lawmakers this week as part of the Fed chairman's semiannual report to Congress. "The labor market, however, has continued to weaken."

Job insecurity could lead consumers to further pull back spending, he said, calling it "an important risk to the outlook."

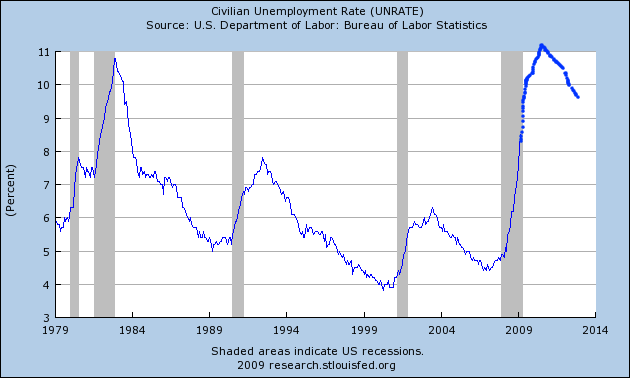

What does all this mean for the course of the labor market? We combine data on involuntary part-time workers with the standard unemployment rate to arrive at an alternative measure of labor underutilization. We plot this measure in Figure 3, which shows that the labor market has considerably more slack than the official unemployment rate indicates. The figure extends this labor underutilization measure using the Blue Chip consensus forecast for the unemployment rate as a benchmark and then adding a share of involuntary part-time workers based on the proportion of workers in that category to the unemployed during the current recession. This projection indicates that the level of labor market slack would be higher by the end of 2009 than experienced at any other time in the post-World War II period, implying a longer and slower recovery path for the unemployment rate. This suggests that, more than in previous recessions, when the economy rebounds, employers will tap into their existing workforces rather than hire new workers. This could substantially slow the recovery of the outflow rate and put upward pressure on future unemployment rates.

LARGE TRADE DEFICITS have bedeviled the U.S. for much of the past 20 years. Although puritanical critics have attributed these imbalances to a nation content to live beyond her means, Paulsen sees other factors at work. For one thing, most U.S. administrations over that period, and even during the 1980s, favored a strong-dollar policy (at least until 2002). This was in reaction to the economic traumas of the '70s when the U.S.'s weak-dollar policies helped spur hyperinflation.

Likewise, the U.S. also closely hewed to free trade, even though the policy, along with a strong dollar, cost the nation dearly in terms of manufacturing jobs. Foreign goods displaced U.S. products both here and abroad. This was a major reason why real annual GDP growth from 1982 through the end of 2006 averaged about 3.3%, while such growth from 1950 to 1980, when trade deficits weren't a problem, approached 4%. According to Paulsen, foreigners in recent decades were capturing some fruits of the U.S.'s consumer spending binge.

Yet Paulsen sees a silver lining to this leakage of U.S. demand to overseas.

In the process of gorging on overseas goods and services, the U.S. by happenstance fired up emerging economies such as China, Korea, Taiwan, India, Brazil and Mexico to build their productive capacities and spawn their own middle classes and consumer cultures. Paulsen has long called this trend the U.S.'s "emerging-market Marshall Plan."

In the strategist's view, the emerging-market demand will constitute "an incredible asset" for U.S. and other developed nations' goods and services. So far, the post-2002 weakening of the dollar has only helped U.S. trade competitiveness versus developed trading rivals such as Japan, the European Union and the U.K. That is because many emerging-world nations have been allowed to peg their currencies to the dollar -- or, like China, have made only desultory moves to strengthen their currencies. But U.S. trade competitiveness should benefit mightily from the likelihood that these currencies will no longer be able to maintain their pegs at ridiculously low levels.

Aggressive policy actions taken around the world last fall may well have averted the collapse of the global financial system, an event that would have had extremely adverse and protracted consequences for the world economy. Even so, the financial shocks that hit the global economy in September and October were the worst since the 1930s, and they helped push the global economy into the deepest recession since World War II. The U.S. economy contracted sharply in the fourth quarter of last year and the first quarter of this year. More recently, the pace of decline appears to have slowed significantly, and final demand and production have shown tentative signs of stabilization. The labor market, however, has continued to weaken. Consumer price inflation, which fell to low levels late last year, remained subdued in the first six months of 2009.

To promote economic recovery and foster price stability, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) last year brought its target for the federal funds rate to a historically low range of 0 to 1/4 percent, where it remains today. The FOMC anticipates that economic conditions are likely to warrant maintaining the federal funds rate at exceptionally low levels for an extended period.

At the time of our February report, financial markets at home and abroad were under intense strains, with equity prices at multiyear lows, risk spreads for private borrowers at very elevated levels, and some important financial markets essentially shut. Today, financial conditions remain stressed, and many households and businesses are finding credit difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, on net, the past few months have seen some notable improvements. For example, interest rate spreads in short-term money markets, such as the interbank market and the commercial paper market, have continued to narrow. The extreme risk aversion of last fall has eased somewhat, and investors are returning to private credit markets. Reflecting this greater investor receptivity, corporate bond issuance has been strong. Many markets are functioning more normally, with increased liquidity and lower bid-asked spreads. Equity prices, which hit a low point in March, have recovered to roughly their levels at the end of last year, and banks have raised significant amounts of new capital.

Many of the improvements in financial conditions can be traced, in part, to policy actions taken by the Federal Reserve to encourage the flow of credit. For example, the decline in interbank lending rates and spreads was facilitated by the actions of the Federal Reserve and other central banks to ensure that financial institutions have adequate access to short-term liquidity, which in turn has increased the stability of the banking system and the ability of banks to lend. Interest rates and spreads on commercial paper dropped significantly as a result of the backstop liquidity facilities that the Federal Reserve introduced last fall for that market. Our purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities and other longer-term assets have helped lower conforming fixed mortgage rates. And the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), which was implemented this year, has helped restart the securitization markets for various classes of consumer and small business credit.

Earlier this year, the Federal Reserve and other federal banking regulatory agencies undertook the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP), popularly known as the stress test, to determine the capital needs of the largest financial institutions. The results of the SCAP were reported in May, and they appeared to increase investor confidence in the U.S. banking system. Subsequently, the great majority of institutions that underwent the assessment have raised equity in public markets. And, on June 17, 10 of the largest U.S. bank holding companies--all but one of which participated in the SCAP--repaid a total of nearly $70 billion to the Treasury.

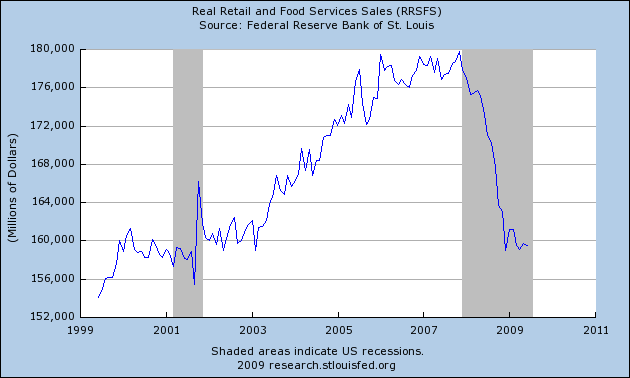

Better conditions in financial markets have been accompanied by some improvement in economic prospects. Consumer spending has been relatively stable so far this year, and the decline in housing activity appears to have moderated. Businesses have continued to cut capital spending and liquidate inventories, but the likely slowdown in the pace of inventory liquidation in coming quarters represents another factor that may support a turnaround in activity. Although the recession in the rest of the world led to a steep drop in the demand for U.S. exports, this drag on our economy also appears to be waning, as many of our trading partners are also seeing signs of stabilization.

Despite these positive signs, the rate of job loss remains high and the unemployment rate has continued its steep rise. Job insecurity, together with declines in home values and tight credit, is likely to limit gains in consumer spending. The possibility that the recent stabilization in household spending will prove transient is an important downside risk to the outlook.

Though manufacturing has long been in decline, the loss of factory jobs has been especially brutal of late, with nearly two million disappearing since the recession began in December 2007. Even a few chief executives, heading companies that have shifted plenty of production abroad, are beginning to express alarm.

“We must make a serious commitment to manufacturing and exports. This is a national imperative,” Jeffrey R. Immelt, chairman and chief executive of General Electric, said in a speech last month, while acknowledging that G.E. was enriched by its overseas operations too.

President Obama, agreeing in effect, has declared, “The fight for American manufacturing is the fight for America’s future.”

The United States ranks behind every industrial nation except France in the percentage of overall economic activity devoted to manufacturing — 13.9 percent, the World Bank reports, down 4 percentage points in a decade. The 19-month-old recession has contributed noticeably to this decline. Industrial production has fallen 17.3 percent, the sharpest drop during a recession since the 1930s.

So far, however, Mr. Obama’s administration has not come up with a formal plan to address the rapid decline. Instead, it has pursued ad hoc initiatives — bailing out General Motors and Chrysler, for example, and pushing green energy by supporting the manufacture of items like wind turbines and solar panels.

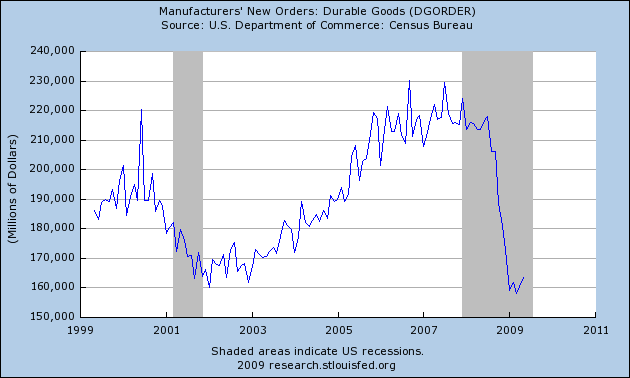

The Conference Board LEI for the U.S. increased for the third consecutive month in June. Most of the components contributed positively to the index this month except real money supply* and manufacturers' new orders for nondefense capital goods*. The six-month change in the index has risen to 2.0 percent (a 4.1 percent annual rate) in the period through June, up substantially from - 3.1 percent (a –6.2 percent annual rate) for the previous six months, and the strengths among the leading indicators have remained balanced with the weaknesses in recent months.

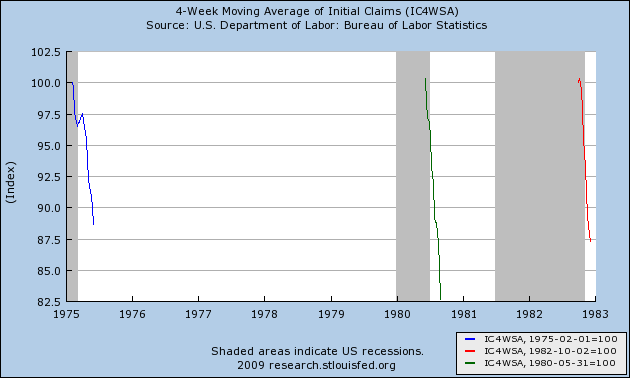

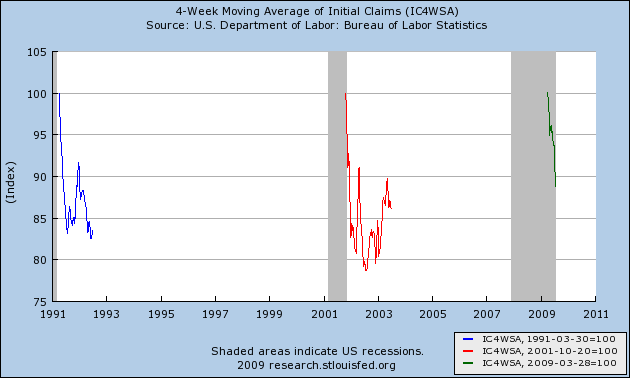

| Year | Mo./-12% | Mo./-16% | Mo./peak unemployment | range/ jobless claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970-71 | 1/71 | 2/71 | 11/70 | n/a |

| 1974-75 | 5/75 | 7/75 | 5/75 | n/a |

| 1980 | 7/80 | 8/80 | 7/80 | n/a |

| 1982 | 10/82 | 11/82 | 12/82 | n/a |

| 1991-92 | 9/91 | 7/91, 6/92 | 6/92 | -8% to -16% |

| 2001-03 | 12/01 | 2/02, 6/03 | 6/03 | -7% to -21% |

"[O]ften a sharp economic downturn is followed by an equally sharp economic recovery. One reason for that is the liquidation of inventories that accompanies any recession and restocking that takes place in recovery.

"The typical pattern is for inventory investment to fall well below trend during an economic downturn. ...[S]ince the current recession began in 2007:Q4 ... the level of inventories is lower than you would have expected in the absence of a recession by about ... 0.91% of one year's GDP. Add that restocking to the normal [ ] inventory investment that we'd expect ..., and you get a possible contribution of inventory investment of ... 1.12% of GDP during the first year of the recovery.

"If we are looking at the growth rate of real GDP, which is how we usually think about these numbers, the potential contribution of inventory investment is even more dramatic. If inventory investment goes from subtracting 0.49% from GDP (as it did over the last 4 quarters) to adding 1.12% to GDP ..., the contribution to the growth rate of real GDP would be 1.12 - -0.49 = 1.61%."

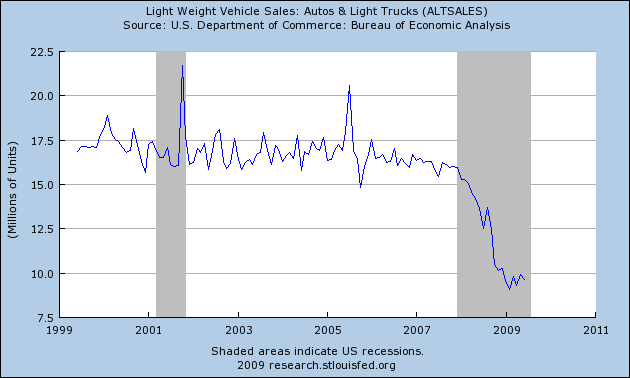

"similar dynamics also apply to a number of other components of GDP. For example, recent sales levels for motor vehicle appear to be significantly below normal scrappage rates, and this is another area where a big rebound effect is quite possible."Similarly, Calculated Risk has noted that the

"turnover ratio for the U.S. fleet [of cars] ... for January [2009] is 27 years, by far the highest ever. The actual in December was close to 24 years. This is an unsustainable level...."

on about September 10, we saw our business fall off 30-35%.

it might motivate people that haven't been paying attention to say: "Wow, this is bad. Let's make sure our money is safe, and watch our expenditures." And that could lead to a deeper recession."And indeed American families abruptly and severely cut spending.

Question of the day: Does being a supply-sider mean that you pay no attention whatsoever to the demand side of the equation or other factors that may be at play?

Taking a page from Art Laffer's June Wall St. Journal op-ed, Jerry Bowyer is sounding the inflation alarm because of all the money that's "sloshing around the system."

Laffer used the following chart in his Journal op-ed to make his point:

Instead of YoY percentage change, Bowyer looks at the same data (or something very close to it) in terms of dollar change from year-ago levels:

Mr. Bowyer asks: "But what happens when the floodgates open? At some point the banks will have to release a river of liquidity. Consumers are demanding it, Congress is demanding it, and even President Obama is demanding it. (That last one may well be the clincher.)"

(Let's leave aside for the moment that consumers are demanding no such thing and that no matter how much pressure Congress or the president put on the banks, no one can force consumers to borrow.)

It's pretty scary stuff, eh, all this liquidity sloshing around the system?

Before I even get to the gist of the matter, let's just dispense with Mr. Bowyer's nonsensical claim that "consumers are demanding" that banks open their "floodgates" and begin lending again.

As Exhibit One and Exhibit Two (and I probably don't need to go any further), I offer up – via the Federal Reserve – the delinquency rates on residential real estate loans and credit cards:

Yup. Consumers, who are delinquent on their obligations in record numbers, are clamoring for more credit. How some folks are so comfortable writing fact-free pieces is simply beyond me.

Anyway, here's the point that Mr. Laffer and Mr. Bowyer are apparently missing (as evidenced by the two charts above): There's no demand for the money that's "sloshing around the system," and there likely isn't going to be for some time to come – and by that I mean years, not months or quarters.

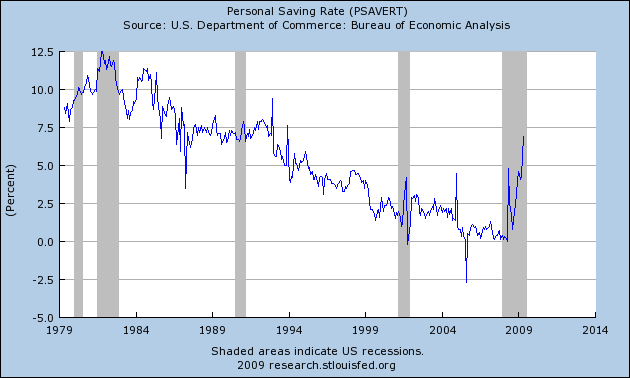

Our 25 year experiment with debt and leverage is over. Done. Finished. Not coming back any time soon. As you read what follows, read it in the context of the fact that the US consumer has, for the past 8 years, represented approximately 70% of our nation's GDP (roughly $10 out of $14 trillion).

I wrote about our debt-to-income ratio here in February 2008. At that time, the level was 138%, and I asked if that was sustainable. Clearly it was not, as it peaked at 139%, before turning down, and sits now at 131%:

The mean of this metric is 77%. To get back to that mean – and I'm not suggesting we'll get there – in the absence of an increase in DPI implies a decrease in liabilities of $5.8 trillion dollars. Not the stuff of which inflation is made, and not the stuff that has me worried about an $800 billion increase in the monetary base. Now, keep in mind that "organic" income has not been growing, in fact it has been shrinking. The only component of income that has been growing is Government Benefits.

Other metrics tell a similar story. Here is Household Debt Service Payments as a Percent of Disposable Personal Income:

As I've mentioned before, Baby Boomers – defined as those born between 1946 and 1964 – will not be coming to the rescue, as the median boomer (born 1955) was 52 when this recession started. He (or she) will not be propping up the economy as was the case in previous recessions when s/he was much younger and still consuming and/or trading up:

Look at the growth of the accumulation of "stuff" – consumer durable goods – over the past 29 years:

(Number of Households: Census.gov. Durable Goods: Flow of Funds, Table B.100, Line 7)

Not only will we not be buying much more stuff than we've already got, we've begun storing our current stash of belongings at an alarming rate. Some tidbits from the Self Storage Association (the first two are truly staggering):

It's been fascinating over the past many months to read the commentary that has treated this recession as a typical garden-variety type that will resolve itself as most of those in the post-war era have. Doing so severely understates the magnitude of the changes we are undergoing, from a secular change in the way we view and use credit to the adverse effects of our demographics.