- by New Deal democrat

Prof. Menzie Chinn at Econbrowser, like me, is an Old School blogger, and like me, is focused on forecasting.

Yesterday he wrote a piece about supplementing the yield curve with a second condition, the private nonfinancial debt service ratio. Basically, what percent of income is needed to service debt. Doing so retrospectively indicated far less of a chance that the economy would fall into recession between 2022 and now.

I am always a little concerned about “just so” indicators that retroactively fit something without either a fundamentals’based justification, or a testable prediction for the future. So let me venture into that territory in this post.

There has always been discussion about why exactly an inverted yield curve should indicate a recession is oncoming. The best explanation I have heard is that banks borrow short (from depositors) and lend long. An increase in short term rates means that banks must pay out more in deposit rates, and that means less lending, because to earn a profit those rates must increase as well. Less lending in turn is a factor in an industrial slowdown, which leads to recession.

That paradigm is best shown by comparing the 10 year minus 2 year Treasury spread (I could use other spreads as well) (blue in the graph below) vs. whether banks are tightening or loosening commercial lending conditions (red, inverted so that tightening shows as negative, /10 for scale):

Historically when the yield curve has inverted, lending has tightened. That did happen in 2022 and early 2023, but pressure to tighten lending conditions eased up beginning in Q3 2023 - something that typically has happened coming *out* of recessions, rather than going in to one.

One reason why this may have been the case has to do with supply chain tightness. The NY Fed’s Supply Chain tightness Index is shown below in two installments (a positive value indicates increased tightness):

Note that before 2020 this index had almost never, even during the Great Recession, had a value higher than 1. But beginning in 2020 through 2022 it rose to levels as high as 4.5. Since the beginning of 2023 it has resumed being completely normal.

The return to normalcy meant the supply curve shifted sharply to the left. Commodity prices on average fell by almost 10% YoY - a hurricane force tailwind behind producer profits. Nonfinancial producers hardly had to worry about bank lending conditions.

And despite the lending conditions survey data shown above, financial conditions adjusted for background conditions (blue in the graph below) or as affecting leverage (red) both remained very positive (again, for these indexes negative = loose) for the entire duration of this expansion, with the brief exception of the Silicon Valley Bank failure in early 2023:

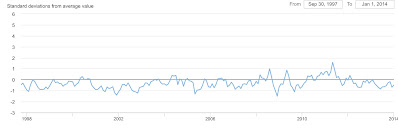

A similar result is obtained from the St. Louis Fed’s Financial Stress Index (again, negative = less stress):

Aside from the tailwind provided by the un-kinking of the supply chain, another major factor may be the interest earned by banks on their Fed reserve deposits, which has been allowed since 2008 (blue in the graph below), in contrast to their CD rates (red):

During the entire period that the Fed raised interest rates, banks could earn substantially higher interest on their money parked with the Fed, than they had to pay out to depositors.

Under those conditions, who cares if the Fed rate hikes have inverted the yield curve?

The above has been a look at the economic fundamentals of why the inverted yield curve gave a poor signal in the past several years. And it is testable. *If* (1) the supply chain index remains within its normal limits, and (2) bank deposit interest rates exceed the interest rate paid by the Fed for bank reserves, *then* the financial stress indexes should indicate higher stress, and an inverted yield curve will again forecast a recession. If that doesn’t occur, a recession is not likely.

We’ll see.