- by New Deal democrat

In my summation of Friday’s employment report, I wrote that “[t]here will probably be lots of chatter in the next few days as to whether the “Sahm Rule” has been triggered. It has not, because the 3 month average in the unemployment rate is 4.0%, and the lowest 3 month average in the last year is 3.6%. Additionally, Claudia Sahm herself has indicated that the same immigration issue I have highlighted may also make her metric signal a false positive this time.”

And right on cue, the usual suspects have pounced. So let’s take a more in-depth look.

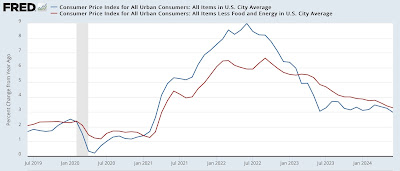

To be clear, the data is pretty close to triggering the “Sahm Rule.” Here’s the real time indicator from FRED from which I have subtracted the 0.5% threshold so that it shows at zero, first for the post-pandemic period:

And now for the pre-pandemic period:

In the past, there have only been three occasions - 1967, 1976, and 2002 - when the current level has occurred in the absence of a recession. Indeed, more often than not, once the 0.3% threshold has been crossed, a recession has been close to occurring.

But as I wrote last month, and as Sahm herself as well as Harvard econ professor Jason Furman have suggested, this time might indeed be different because of immigration.

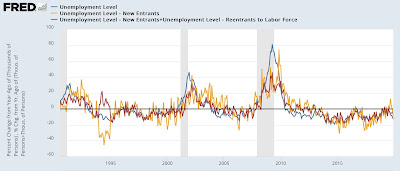

Let’s start with a long term graph I have run many times before: the YoY% change in initial unemployment claims (red) vs. the YoY% change in the unemployment rate, prior to the pandemic:

It is crystal clear that initial claims, for over half a century, have led the unemployment rate.

Now let’s look at the last three years:

Despite the fact that initial claims have turned *lower* YoY ever since the beginning of the year, the unemployment rate YoY has continued to climb.

This is unprecedented. There has not been a single time at any point in the past 50+ years when initial claims have been declining YoY and the unemployment rate has not followed suit. Not once!

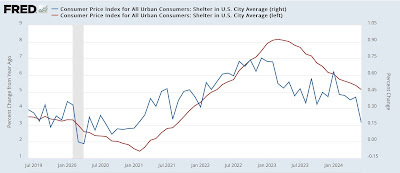

But the unemployment rate might rise because jobs are harder to find (essentially a demand side issue), or it might rise because there is a surge in people trying to find a similar amount of jobs (a supply side issue). To see which has been more important, let’s slice and dice the recent number of unemployed (blue in the graphs below) by the number of permanent job losers (gold), and also new entrants (like recent immigrants) plus re-entrants (red):

Since the low in December 2022, the total number of unemployed has risen by 1.113 million. Of that, only 261,000 have been permanent job losers. By contrast, new and re-entrants to the labor force have increased by 514,000, about double the number of job losers!

By contrast, here is the historical record pre-pandemic:

We only have a full record going back 30 years, but in that period of time before both pre-pandemic recessions, permanent job losers increased sharply, while new and re-entrants to the labor force stayed steady or even declined.

This strongly suggests a supply side explanation.

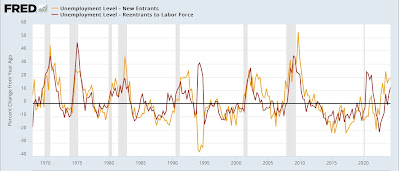

Another way to look at similar data is to break out new entrants, like recent immigrants (gold in the graphs below) from total unemployed (blue again) and new plus re-entrants (red again):

We can see that both new and re-entrants have increased in the last several years.

Now here is the pre-pandemic comparison:

Only during the 1980-81 “double-dip” recession period did new and re-entrants increase prior to a recession.

And just how much have new and re-entrants increased? By about 20% YoY for new, and over 10% for re-entrants in the past year, a considerably higher rate than total unemployment:

Such an increase was almost totally unprecedented in the 50 years before the pandemic:

In fact, in addition to the 1980-81 double-dip period, significantly the only other time it even came close was 1968-69, when the Baby Boom was entering the labor force in droves.

Indeed, going back 60 years, the 20%+ increase in unemployment in new entrants, and 10%+ increase among re-entrants has only been seen coming *out of* recessions, not going in to one:

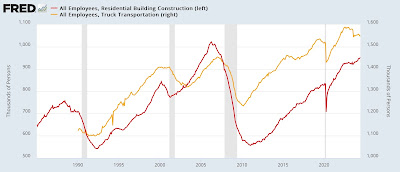

With that in mind, let’s again take a look at the increase in the native born (blue) and foreign born (red) labor force since the onset of the pandemic:

The native born labor force declined much more sharply, and only in the past two months has exceeded its pre-pandemic level, while the foreign born labor force has exceeded its pre-pandemic level by roughly 1,000,000.

And now remember that the population figures I have been using above have probably undercounted post-pandemic immigration to the US by over 3 million, and the number of recent immigrants in the labor force by 2 million!

Put this together, and the picture painted is not one of a labor market where the demand for workers has gone soft, but primarily where the supply of new workers, especially recent immigrants, as well as re-entrants to a strengthening market, has swamped the number of positions available.

And because so much of the increase in labor supply is driven by people who were not previously part of the US economy (because they were foreigners), it is perfectly compatible to have both a growing economy (i.e., one not in recession) and an increasing unemployment rate.