| Year | Nonfarm housing starts | 2009 equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 247 | 699 |

| 1921 | 449 | 1236 |

| 1922 | 716 | 1953 |

| 1923 | 371 | 994 |

| 1924 | 893 | 2350 |

| 1925 | 937 | 2423 |

| 1926 | 849 | 2177 |

| 1927 | 810 | 2042 |

| 1928 | 753 | 1867 |

| 1929 | 509 | 1252 |

| 1930 | 330 | 805 |

| 1931 | 254 | 615 |

| 1932 | 134 | 322 |

| 1933 | 93 | 221 |

| 1934 | 126 | 300 |

| 1935 | 221 | 522 |

| 1936 | 319 | 748 |

| 1937 | 336 | 781 |

| 1938 | 406 | 937 |

| 1939 | 515 | 1179 |

| 1940 | 602 | 1368 |

President Barack Obama and congressional leaders might extend or expand tax credits and housing aid as they seek to counter the decline in the U.S. housing market and reverse rising job losses.House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said lawmakers might extend an $8,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers that is set to expire Dec. 1.

.....

Extending the tax credit for homebuyers is “under consideration,” Pelosi, a California Democrat, told reporters today in Washington. “The question is, would that be just first-time homeowners or would you open it up to other purchasers of homes?”

“There’s no question that I think it should be extended; for how long, we should discuss,” said House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Charles Rangel, a New York Democrat. He said the tax credit shouldn’t be made permanent.

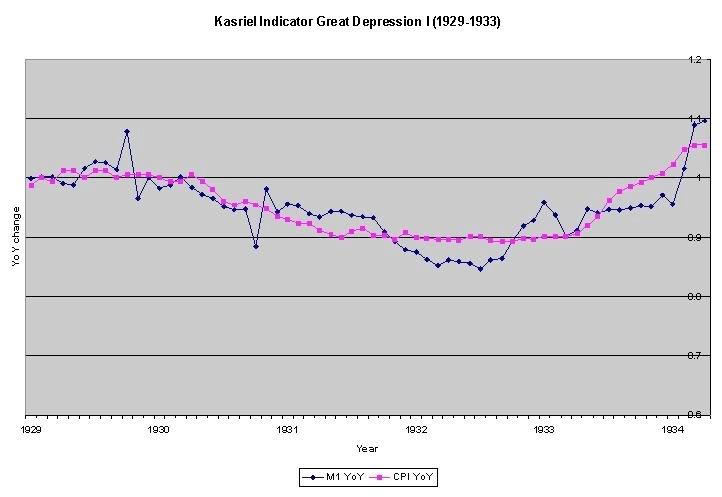

A general decline in prices, often caused by a reduction in the supply of money or credit. Deflation can be caused also by a decrease in government, personal or investment spending. The opposite of inflation, deflation has the side effect of increased unemployment since there is a lower level of demand in the economy, which can lead to an economic depression. Central banks attempt to stop severe deflation, along with severe inflation, in an attempt to keep the excessive drop in prices to a minimum.

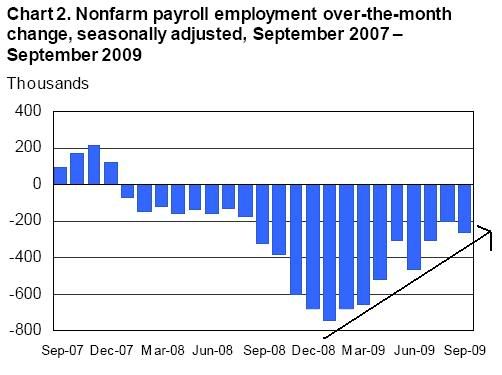

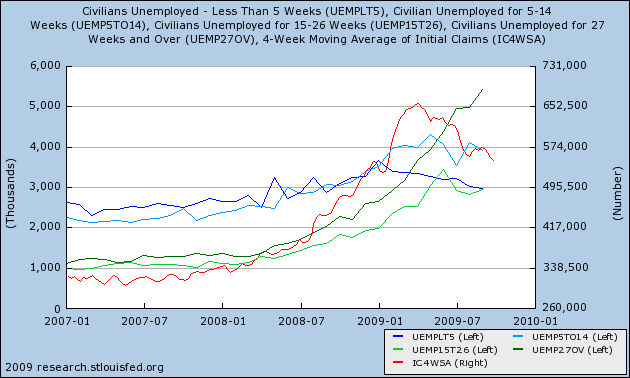

dropped 33,000 to a seasonally adjusted 521,000 in the week ended Oct.3, the lowest level since early January, the Labor Department said.This is the lowest weekly number, and the lowest four week average for new jobless since mid-January of this year.

Analysts polled by Reuters had forecast new claims slipping to 540,000 last week from a previously reported 551,000. A Labor Department official said seasonal factors expected a decline in new claims at the end of a quarter and a rise at the start of a new quarter.

The four-week moving average for new claims fell 9,000 to 539,750 last week, declining for a fifth straight week. The four-week moving average is considered a better gauge of underlying trends as it irons out week-to-week volatility.

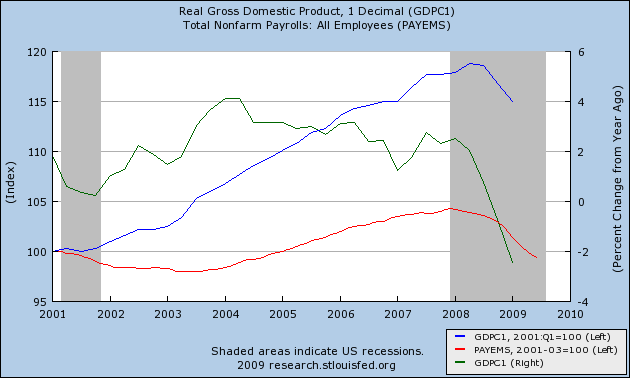

In the job market, at least, the recession’s pain has been unusually concentrated. ... People who have lost their jobs are struggling terribly to find new ones. Since the downturn began in 2007, companies have been extremely reluctant to hire new workers, and few new companies have started. The economy and the job market are churning very slowly....

Try thinking of it this way: All of the unemployed people in the country are gathered in a huge gymnasium that’s been turned into a job search center. The fact that this recession is the worst in a generation means that there are many, many people in the gym. The fact that the economy is churning so slowly means that there is not much traffic into and out of the gym.

If you’re inside, you will have a hard time getting out. Yet if you’re lucky enough to be outside the gym, you will probably be able to stay there. The consequences of a job loss are terribly high, but — given that the unemployment rate is almost 10 percent — the odds of job loss are surprisingly low.

The idea of a tax credit for companies that create new jobs, something the federal government has not tried since the 1970s, is gaining support among economists and Washington officials grappling with the highest unemployment in a generation.

.....

One version of the approach, to be unveiled next week by the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research organization, would give employers a two-year tax credit if they increased the size of their work force or added significant hours of work (for example, making a part-time worker full time). Employers would receive a credit worth twice the first-year payroll tax for each new hire, amounting to several thousand dollars, depending on the new worker’s salary.

...

[a second proposal would be] a credit in the first year ... equal to 15.3 percent of the cost of adding an employee. In the second year, it would fall to about 10.2 percent.

For example, hiring a worker might cost a small business $50,000 annually. But with the tax credit, the cost would fall to $42,350 in the first year, and then be $44,900 the next year. After that, the cost would return to $50,000.

The credit would apply only to the portion of an employee’s salary under $106,800. Lowering the cap further, however, could provide an even greater benefit to low-wage, unskilled workers.

- "Sales are very steady and have risen some each month in the past six months. The bottom is now here." (Construction)

- "Economic recovery turnaround has begun in the financial services sector; however, cautious expense management is still practiced." (Finance & Insurance)

- "Lack of capital available for new project development." (Accommodation & Food Services)

- "Continue to see signs of slow recovery, but customers are still putting orders off until the beginning of 2010." (Professional, Scientific & Technical Services)

- "Inconsistent ... just when things seem to be settling a bit, a new set of pressures develops." (Retail Trade)

- "Improvements seen in prices available for natural gas and other fuels." (Educational Services)