Its lanes will be taken over by the giant trucks from powerful economies… Bangladeshi rickshaws will be thrown off the highway.Further, as The Times paraphrased Yunus as saying:

While international companies motivated by profit may be crucial in addressing global poverty…nations must also cultivate grassroots enterprises and the human impulse to do good.Yunus has accomplished untold good for his nation’s impoverished citizens, even as he and others for years have sounded the alarm about the negative impact of globalization on the world’s most impoverished. But more and more, it’s not only the poor who are being run off the road. America’s middle class increasingly finds itself faced with the effects of globalization—and seemingly no way to stop the collision. And white-collar professionals are among those now in the headlights.

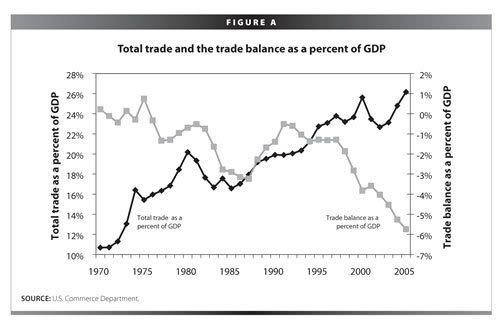

The United States always has traded with other nations—but until the 1970s, the international share of the U.S. economy was modest, and exports and imports were generally in balance or showed a small surplus. As Economic Policy Institute (EPI) economist Jeff Faux notes:

...in the last 25 years, foreign trade has risen 700 percent, more than doubling as a share of gross domestic product to 28 percent. In 2006, the excess of imports over exports will reach some $900 billion—7 percent of GDP [gross domestic product].

Faux’s briefing paper, “Globalization That Works for Working Americans,” was released Jan. 11 at the launch of a new network of progressive economists, the Agenda for Shared Prosperity. In it, he continues:

This dramatic shift reflects more than simply an increased movement of goods and services between the United States and other nations. It reflects an unprecedented economic integration with the rest of the world that is blurring the very definition of the "American" economy.As EPI economist Larry Mishel puts it, more trade, regardless of its terms, is not better for all of us. For many working Americans, the huge growth in foreign trade has resulted in the loss of family-supporting jobs, downward pressure on wages and increased inequality: From 2000 to 2005 alone, 3 million manufacturing jobs disappeared, at least one-third because of our trade deficit. But the greatest damage has been to wages— Mishel estimates as much as a loss of $2,000–$6,000 annually for the typical household. The doubling of trade as a share of our economy over the past 25 years has been accompanied by a massive trade deficit, directly displacing several million jobs.

American business is steadily moving finance, technology, production, and marketing beyond our borders. Some 50 percent of all U.S.-owned manufacturing production is now located in foreign countries, and 25 percent of the profits of U.S. multinational corporations are generated overseas—and the shares are rapidly growing.

Mishel, who testified Tuesday before the House Committee on Ways and Means, told lawmakers:

That trade will make the distribution of income worse is embedded in fundamental economic logic. When American workers are thrown into competition with production originating from low-wage nations, both those workers employed directly in import-competing sectors and all workers economy-wide who have similar skills and credentials will have their wages squeezed. In fact, at the same time as trade flows with low-wage nations have increased, the distribution of income and wealth in the U.S. has grown more and more unequal.Such a view is not confined to progressive think tanks. David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology The New York Times yesterday:

The consensus until recently was that trade was not a major cause of the earnings inequality in this country. That consensus is now being revisited.After years of thinking the nation’s economic gains were passing primarily by manufacturing workers, middle-class professional and technical workers are recognizing the oncoming car wreck is headed in their direction as well.

Discussing a recent Center for American Progress study, White Collar Perspectives on Workplace Issues, Jim Grossfeld and Celinda Lake wrote on The America Prospect online that “many young, white collar workers are now as bewildered by the ‘new economy’ as manufacturing workers have been for a generation.”

As a 20-something techie in the once bustling Silicon Valley told us: "I think a lot of people, you know, 30 years ago, could get a job that was relatively stable, but, here I am, five years out of school, and I've had four jobs. It's not because I'm not good because I've gotten praise from every single job I've been at. It's just that the fact that the companies don't seem stable."In fact, new data compiled by EPI show employment growth in the past five-year post-recessionary period has been subpar due to a weak economy. This conclusion is supported by the fact that employment rates, which some thought were at the demographically set peaks, have risen sharply in response to job growth and falling unemployment in 2006.

But it's not just that these workers' future career prospects look murkier. The quality of their work lives is tanking, too. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this decline. Technical and professional employees share a profound conviction that their work ought to be intellectually satisfying—even an expression of their values. However, when employers press for cost savings and workloads soar, psychic wages take a plunge. Echoing the sentiments of many of the workers we spoke to, when asked to describe her office, one San Jose woman answered: "Busy, overworked, under staffed, not enough people in the group to do all the work we need to do so everyone's doing a lot of work and just running around like a chicken with a head cut off."

The union movement doesn’t oppose trade and globalization. In fact, it’s precisely because we recognize we live in a global economy that we see a lot of policy changes that should be made at the federal level to enhance the quality and stability of jobs in this nation. And when trade deals are negotiated, they need to do more than line corporate pockets—they need to ensure workers don’t get run off the road.

Faux offers many solutions in his issue paper on globalization, one of many the Agenda for Shared Prosperity will issue in coming months in advance of the 2008 elections on topics such as pension, health care and more. One solution he offers: Eliminate perverse tax incentives.

By law, corporations that invest in the United States pay taxes when they are earned. But corporations that invest overseas can delay the payment of taxes until they repatriate their profits—which can take a long time. In 2005, in order to get some short-term relief to the fiscal deficit, the Congress voted to offer corporations that brought their money back that year a 5.25 percent tax rate, a much lower rate than they would pay on profits made in the United States.In contrast to the Hamilton Project, which supports unfettered globalization, Faux offers many other options to making globalization work for working people. It’s all here.

This loophole might have been justified after World War II as a way of helping Europe and others get back on their feet. But it has long outlived its rationale and should be eliminated.

Indeed, U.S. integration into the global economy requires us to rethink our whole approach to taxation. Other nations, for example, use "border-adjustable" value-added taxes (VATs) to favor exports over imports. A progressive VAT is some-thing that ought to be considered as an instrument to level the playing field.

As AFL-CIO President John Sweeney wrote recently in a USA Today op-ed:

Without dramatic changes in trade policy, we will continue to hemorrhage good jobs, while corporations take advantage of workers whose basic human rights are violated daily.